A proposed development in the Central Area demonstrates why Seattle’s micro-housing of the present does not offer the affordability of the past.

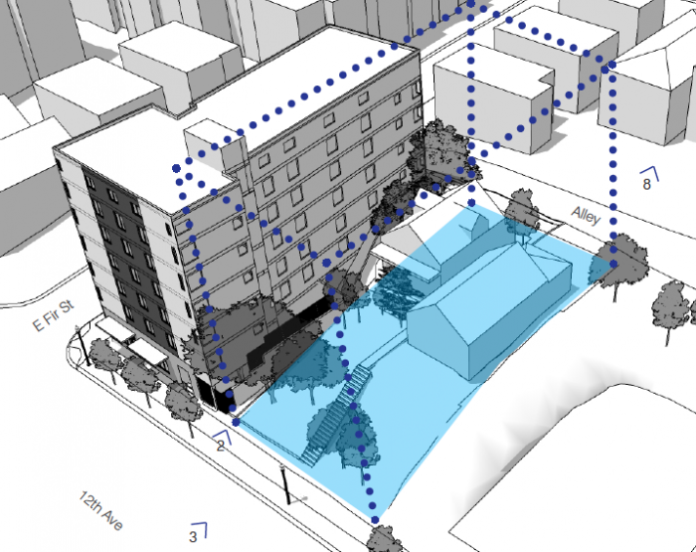

At 159 12th Avenue, plans are moving forward to transform a steep overgrown lot littered with trash into Sound Flats, a seven-story, 78-unit mixed-use building, with a generous front porch intended to infuse the currently neglected sidewalk with life.

For urbanists, there is a lot to like about the Sound Flats’ proposal, which borrows heavily from the newly approved Central Area Design guidelines.

But next-door sits an existing similar — yet different — development, Firenze Apodments, a six-story, 92-unit mixed-use building, with a commercial space occupied by Seattle Seed Company at street level.

A side by side comparison of the two developments tells a story.

It’s story about policy changes. How decisions made in 2013-2016 arguably led to the “death of micro-housing” in Seattle, the city which first raised its profile on the national stage. It also reveals how changes to micro-housing policy are contributing to Seattle’s housing crisis.

In April King County declared an “unprecedented challenge of affordability” for “residents in every community in the county,” one that requires “building, preserving, or subsidizing 244,000 net new healthy homes countywide by 2040.” Nonetheless, Seattle continues to fall short of its affordable housing goals, raising important questions about affordability, design, and housing creation.

The Death of Micro-Housing

The publication of polarizing editorials, such as “Even as a newbie, I know tiny apartments don’t belong in Fremont,” can make it easy to forget that micro-housing was first declared dead in 2016 by Dave Neiman, principal architect at Neiman Taber architects, after new policies regarding minimum unit size and design review requirements were put in place by the City.

To keep the spotlight focused on micro-housing’s decline, Neiman issued a second death notice in 2017.

While micro-housing continues to be promoted across the country in cities both likely (Honolulu) and surprising (Tampa), micro-housing does not appear to be making a comeback in Seattle anytime soon.

Given the King County’s projection of 244,000 needed units, and the visceral awareness of more people sleeping on the street, why does discussion of a return to pre-2013 policies appear to be off the table?

One answer is that the general public is still simply not aware that the micro-housing developments built in 2009-2015, which were mostly congregate housing, and the currently sanctioned micro-housing units, known as SEDUs, cannot be considered as equals because of the significant differences in affordability that exist between them.

Another, is that pre-2013 micro-housing developers were seen as skirting zoning codes and design guideline procedures, which inflamed resistance against micro-housing, feeding distrust that lingers, even in the midst of a housing crisis.

Sound Flats: Micro-Housing of the Present

Sound Flats passed approval for Early Design Guidance (EDG) in August by the newly appointed Central Area Design Review Board.

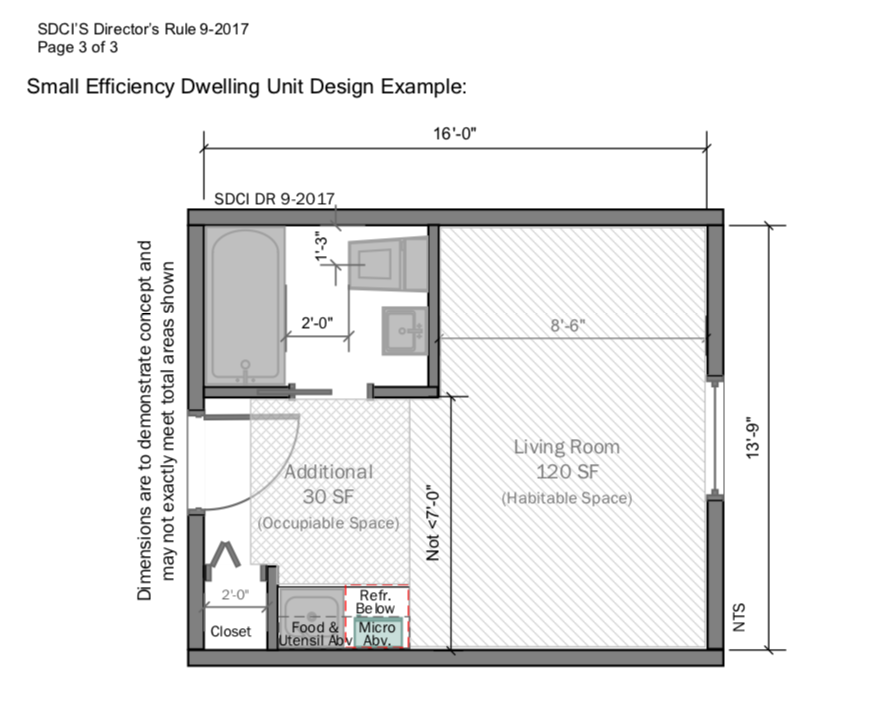

Its 78 residential units include both SEDUs and studios. SEDUs, or Small Efficiency Dwelling Units, were the City’s answer to restrictions placed on micro-housing. According to policy last updated in 2017, SEDUs must:

- Occupy a minimum of 220 square feet, 150 of which must be open space, comprised of at 120 square feet of habitable space (think living/sleeping space) and 30 square feet of occupiable space (standing/walking space).

- Contain a kitchen area with a minimum of four square feet of counter space.

At Sound Flats, SEDUs average 250 square feet, while studios average 380 square feet. The current plan for the typical residential floor includes four SEDUs and 10 studios, which means there will be roughly twice as many studios as SEDUs.

Sound Flats is located within the 12th Avenue urban village which does not require parking, but developers have applied for four parking spots and planned to provide access for loading zones and car sharing.

Based on current prices, studios at Sound Flats would rent for $1,400+ monthly with SEDUs costing $100-$150 less per month.

This amount is taken from the currently advertised $1,585 rent for a 450 square foot studio charged nearby Anthem, as well as $1,680 for a 481 square foot studio charged by Decibel, both of which have been named by Sound Flats architects as “Two recently built projects [that] closely relate to the scale, materiality, and contemporary character of the proposed [Sound Flats] development.”

Of course, by the time the Sound Flats development is actually completed in a couple years rents will likely be higher.

Because of policy changes that occurred in 2014, Sound Flats will need to continue to proceed through a lengthy full design review process, which includes increased opportunity for public feedback and guidance. Passing the EDG is only the first stage of the process.

Prior to 2014, most micro-housing was exempted from full design review, which allowed for the developments to go through less time consuming, and less expensive, administrative design review process.

According to Nick Quijas’ 2018 detailed report in the Seattle Journal of Environmental Law, the current design guidelines make micro-housing economically unfeasible, leading toward a preference for higher cost, but more revenue generating housing types.

The increase in SEDUs and studios over more affordable micro-housing options is part of that trend.

Quijas suggests switching to a “by-right” design policy for micro-housing in which “so long as a proposed project fits existing zoning codes and land use regulations pertaining to the type and size of the development, it is allowed to be produced by-right without being subjected extensive review and approval processes.”

With Seattle’s city and neighborhood design guidelines already in place, “by-right” design policy could lead to more affordable housing being built faster without comprising neighborhood aesthetics and livability.

Firenze Apodments: Micro-Housing of the Past

Unlike Anthem and Decibel, Sound Flats architects also stated they do “not consider the adjacent Apodment project to the south to be a successful contributor to the neighborhood characteristics or architectural patterns of the 12th Ave corridor.”

That neighbor is Firenze Apodments, a congregate housing development that includes 94 sleeping units, each of which has a private bathroom and is furnished with a kitchenette, bed, desk, and chair. The units also have access to a full-sized kitchen and dining area on each floor, as well as coin-operated washer dryers and on-site janitorial service.

Firenze Apodments meets the previous guidelines which allowed for sleeping units that averaged 150 square feet, although the range extended from 90-200 square feet, as long there was access to one fully functioning kitchen for every eight units.

Kitchenette inside a Firenze Apodment, courtesy of Calhoun LLC.

Living Space inside a Firenze Apodment, courtesy of Calhoun LLC.

The size of two lots is similar. Firenze’s lot has been assessed at 7,016 square feet, while Sound Flats’ site is composed of two lots that combine to a total 6,986 square feet.

Firenze Apodments does not offer any parking spaces, but it does provide a loading area in the alleyway behind the development.

There are no units currently available at Firenze Apodments, but rental estimates provided on the website state the average cost for the traditional pod unit to $900, while lofts, available only on first floor of the development, cost $1,035. Unlike Anthem and Decibel, these costs are inclusive of utilities, including WiFi.

Fewer Units and Increased Costs

Restrictions placed on micro-housing have resulted in the production of few housing units and an increase in rental costs for those units. Case in point, Sound Flats will offer 16 fewer units than Firenze Apodments on similar sized lot, which provides comparable commercial space.

Rent at Sound Flats projects to be at least $400-500 more per month than Firenze Apodments, resulting in tenants spending thousands of dollars more on housing annually. According to the Seattle Office of Housing’s 2018 income and rental limits, the average $1,400 rent at Sound Flats would be unaffordable for households earning up to 80% AMI (area median income), or $62,890, annually.

Size Affects Cost, Even for “Luxury” Micro-Housing

For a time, a different form of micro-housing that touted upscale comfort and convenience competed with Apodments for Seattle renters. Sorento Flats, a four-story 159-unit development situated a few blocks south on Yesler Way, is an excellent example of this housing option.

Sorento Flats describes the development as “featuring innovative, space-conscious floor plans, a large interior courtyard, rooftop patio, street level retail… and many other modern and sought after amenities.”

Loft unit, courtesy of Sorento Flats.

Lobby and common space, courtesy of Sorento Flats.

After such hype, one might expect that the Sorento’s rental rates would be similar to Anthem and Decibel; however, they are much closer to those of the Firenze Apodments, offering more proof that size matters when it comes to cost.

During August 27th, conversation with leasing staff, the rates ranged from $1,000 per month for 164-174 square foot units to $1,075 for 204 square feet.

However, for studios units at 325 square feet, rent jumped to $1,600 per month.

Even in this corner of the rental market, Calhoun LLC’s budget Apodment model is winning. A search of the Apodment website revealed, only five units available out the 975 units across 19 developments, resulting .005 vacancy rate. Compare that to the 25.6% vacancy rate in downtown Seattle, where rent averages $2,338 month, and big questions emerge about what exactly the restrictions on congregate and micro-housing have achieved for renters.

Is Seattle Creating Livable Choices for Renters?

In its 2014 Director’s Report and Recommendation, often seen as the end of congregate housing in Seattle, the City stated:

We believe the proposed regulations will improve how this type of housing fits into neighborhoods and make the housing more livable for renters, while continuing to support innovation in housing design to create affordable choices.

Before restrictions were put into place, architects were in competition for how to create more appealing micro-housing for a broader cross-section of renters. With the fewer micro-housing developments being proposed, competition, and subsequent innovation, has decreased. Yobi Apartments, which has been acquired by Seattle University as student housing, is an example of a development that won accolades for its “unique approach to micro-housing that emphasizes small affordable units paired with generous common amenities” was simultaneously lamented as “maybe the last congregate housing allowed in Seattle.”

Earlier this year, The Urbanist reported on a SEDU development in Wallingford that represents “urbanism at its finest.” Imagine if such developments were competing with smaller footprint micro-housing and congregate housing models? Such competition could lead to new designs that appeal to a wider variety of renters at different price points, leading to private market innovation.

While it is clear that a lot of thoughtfulness and intentionality has gone into the design of Sound Flats, it represents a trend toward the production of fewer units at a higher price.

But whether it represents a win or loss is currently does not matter as more SEDU and studio developments continue to be proposed.

Just a few blocks east at 125 15th Avenue, a proposed development will bring 48 SEDUs to a 5,494 square lot. The development markets itself as bringing students and young professionals “quality housing at an affordable rent.”

However, is $1,300-1,400 per month in rent affordable enough? (For comparison, the Multi-Family Tax Exemption affordability program set participating one-bedroom apartment rents at a limit of $1,315 plus utilities in 2017, but the units are larger and the MFTE program is not geared toward deep affordability.) And while current policies are intended to create more livable choices for renters, why are renters continuing to flock to Calhoun LLC’s Apodments? Don’t the low vacancy rates suggest many renters considerable congregate housing a livable option?

Simply put, is it worthwhile to offer renters a modest increase in private space in exchange for a decrease in housing units and increase in rent?

These are some of the many questions that demand answers.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.