The long-awaited consultant report on the Center City Connector is finally out, and while sticker shock has been dominating the headlines, the case for building the streetcar extension remains strong. That may be why Mayor Jenny Durkan chose to release the initial summary of the report on a Friday afternoon before Labor Day. The report largely confirms ridership forecasts and predicts the streetcar may even turn a profit after the first initial investment is made.

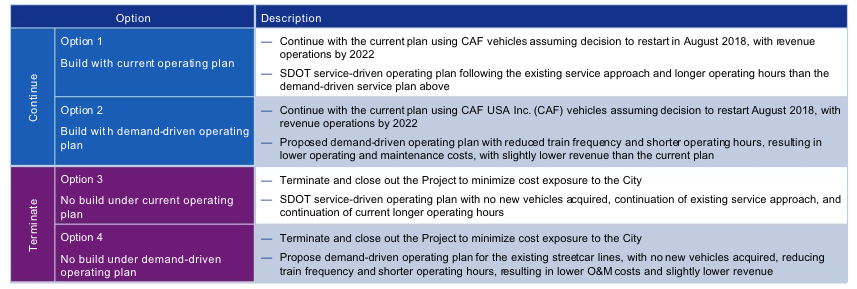

The mayor tapped KPMG, one of the Big Four accounting firms, for the review, though the firm does not specialize in transportation consulting. The initial summary does shed some light on financials and ridership, although high-level recommendations are still being hashed out. The report also outlines four options that the city could consider, including proceeding with the baseline build plan, a modified demand-driven operating plan that would still involve the baseline build plan, a status quo no build plan, and a no build plan that reduces streetcar service.

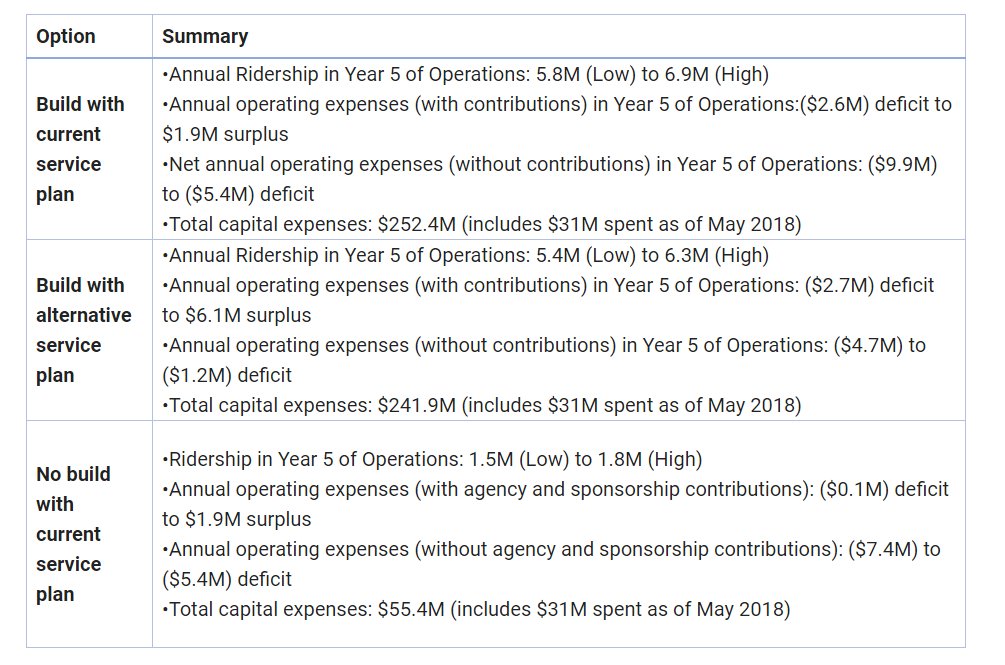

KPMG estimates year-five ridership will range from 18,700 to 22,000 daily weekday passengers (based on their 5.83 million to 6.86 million annual rides). The initial numbers are slightly less vigorous than original projections by the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) several years ago, which suggested 20,000 weekday passengers initially. The report projects about 16,600 to 19,500 weekday riders in year one, based on its range of 5.17 million to 6.08 million first-year trips. The longer-range projections suggest ridership demand will gradually pick up in the years ahead. 22,000 weekday riders would put streetcar ahead of even the busiest bus line in Seattle, which is the RapidRide E at 17,000 weekday riders on a 12.5-mile corridor. Unlike typical ridership estimates, however, the report uses a very narrow projection window through 2026 (most models look out twenty years).*

How we got here

Mayor Durkan commissioned the third-party review (at an initial cost of $416,000) in March following revelations that capital costs had increased–like many construction projects across the region during this breakneck building boom–and the project was short about $23 million. These concerns also led to the mayor to order a temporary hold on the streetcar project, although utility work that had been lumped into the price tag continued. The mayor placed the hold despite SDOT projections that the delay could rack up $10 million or more in added project costs.

Report muddies the capital costs picture

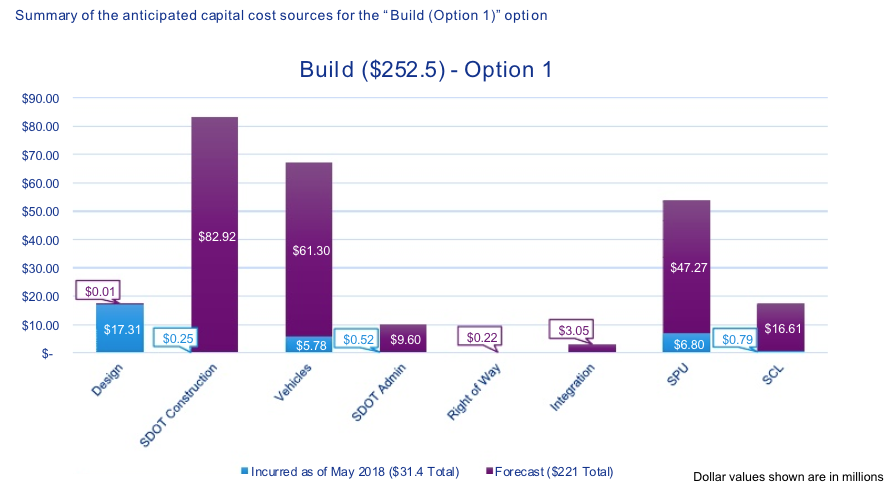

The big headline for most news outlets was that the streetcar’s capital costs had risen to $252.5 million. KPMG’s projected range actually starts at a low-end estimate of $236.1 million and extends to a high-end of $252.5 million–putting the mid-range estimate at $244.3 million.

Meanwhile the “No Build” option is presented at $51.5 million at the low end to $55.4 million at the high end. The report admits that the estimate does not account for costs associated with litigation and risk related to the utility work. Thus even doing nothing on the transit front is expensive and risky. And of course Seattle would lose $75 million in federal grants. Cancellation may also risk losing hundreds millions more in future grant requests for transit projects, including the city’s ambitious RapidRide expansion program.

What are the sources of cost increases?

The source of the project’s cost increases isn’t yet entirely clear. The summary does include the following breakdown:

- “Approximately $7.2 million in new startup costs and approximately $130,000 in items that were not captured in the latest project estimate.”

- “Approximately $9 million dollars was added to the primary continuation options to account for the risk of estimate uncertainties.”

- “Approximately $8 million dollars in escalation costs will be incurred if the Project timeline is extended into 2022. This amount will continue to increase with project delays.”

- “Approximately $19 million in additional design, vehicles, start-up, administrative and construction costs were added to the original estimate after scope reviews in March 2018.”

- “Approximately $11 million in adjusted utility scope and management costs.”

Reading between the lines, it appears Mayor Durkan’s delay is a major cost driver, perhaps the primary one. SDOT originally pegged the cost of the delay at the $10 million to $14 million range, but as the review has dragged on with no clear end in sight, costs seemed to have climbed. Rising construction costs are certainly related to delaying the project and getting contracts out later in a time of skyrocketing prices for contractors. Inflation paired with rising interest rates will also take its toll the later the project drags on.

The $244.3 million price tag then appears to include something on the order of $70 million in utility work. Some of those utility expenses seem to be a direct result of the streetcar, but some utility work is clearly happening regardless, as a torn up First Avenue attests. The fact that Seattle Public Utilities has tacked a long-overdue Pioneer Square utility upgrade on to the streetcar, doesn’t really make that part of the cost of the transit project. Fairer cost reporting here would make the streetcar seem like less of a runaway train–especially when $11 million of the reported cost increase is from “utility scope and management costs.”

In sum, the initial report’s financials aren’t very illuminating without greater detail.

Option 2: slimmed down service plan

The report looked at two options under the built it scenario. The first is the existing plan, but the second involved what was termed a “demand-driven” service plan–a euphemism for shortening service hours and decreasing trip frequencies off-peak. By running less off-peak hours, KPMG projects the streetcar could reduce operating expenses and only require 14 new streetcar vehicles instead of 17 in the current plan. Year-five ridership would decrease to between 5.4 million to 6.3 million, down about half a million riders off the full service scenario. However, capital costs would decrease $10.5 million and operating costs would go down significantly and apparently revenues only slightly so that net operating cost projections show a $2.7 million to $6.1 million surplus (including external contributions).

Shorter hours and lower frequencies are a downgrade from a user standpoint, but the slimmed down service plan may be a viable path to getting the streetcar project built. Once the streetcar is built and it proves its value, more streetcar vehicles could be purchased to increase frequencies and attract more riders.

Streetcar farebox recovery ratio would exceed 52%

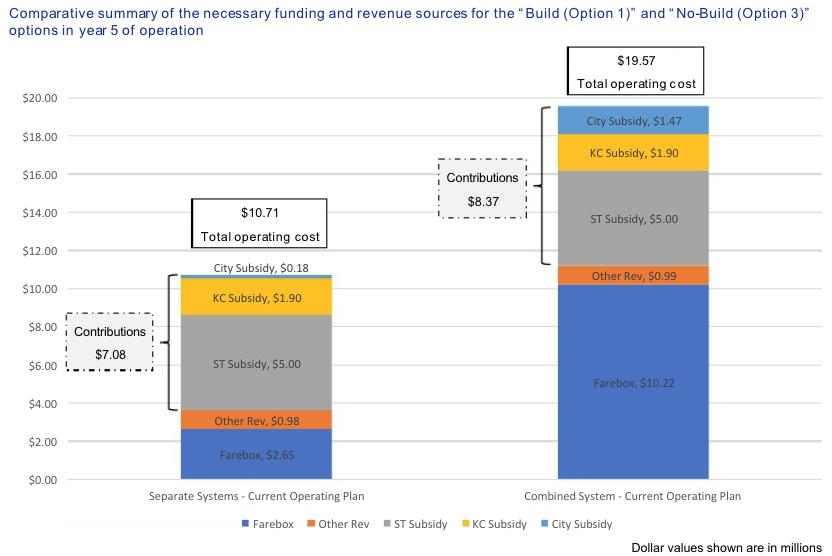

At her streetcar report press briefing last Friday, Mayor Durkan apparently said she remained committed to transit. She acknowledged that subsidies are how any form of transit operates in Seattle, while at the same time clinging to the concept of breaking-even and holding the streetcar to a special standard.

“Durkan emphasized in today’s briefing that nearly all transit programs are subsidized at some level, but that has little reflection on whether they are worth doing,” Kevin Schofield reported. “That said, she and Noble emphasized the extent to which the streetcars are dependent on subsidies from Sound Transit, Metro, and the FTA to be even close to break-even.”

Painting the Center City Connector as particularly dependant on subsidies is misleading since its farebox recovery ratio actually projects to exceed 52%, much higher than King County Metro bus service, which was 27.3% in 2017. Advertising revenue should help further defray cost for the streetcar, although the KPMG audit doesn’t look at how advertising revenue could be increased with additional service through the busiest part of the city.

It’s also worth noting that not just transit operates with a subsidy, but essentially every form of transportation. Highway projects are hardly self-sustaining since gas tax receipts have fallen well short of highway costs for decades and most jurisdictions have filled in the transportation budgets with general funds and tax measures. The city’s own Move Seattle Levy will pony up loads of cash for expensive boondoggle road projects that similarly are unfunded by local user revenues. Moreover, the city subsidizes Metro to the tune of about $40 million annually in order to boost frequency through the voter-approved Seattle Transportation Benefit District.

The problem the streetcar has is that it doesn’t have a dedicated source of operational subsidy going forward. Through its “sorry we screwed First Hill out of light rail” consolation deal, Sound Transit has only promised streetcar subsidies through 2023 and Metro has not indicated it would take the streetcar line on as it would a bus service. It’s a bit of a pickle, but adjusting the next iteration of the Seattle Transportation Benefit District and countywide transit funding measure provides a way out of this mess.

Words versus actions

At her press meeting, Mayor Durkan provided a list of ongoing projects to improve transit to show how her administration is rising to meet the challenge of the “period of maximum constraint.” The question remains if that will be enough to avoid transit meltdowns. The list, via Schofield, includes the following:

- “Extending the transit priority hours on 3rd Avenue;”

- “Under the new bike share program contracts, requiring that bikes are placed at transit centers to help people with the last mile of their trips;”

- “Adjusting signaling speeds and timing to reduce the time the First Hill and SLU streetcars are stuck in traffic;”

- “Distributing ORCA passes to all public school students;”

- “Working with Metro to increase West Seattle water taxi service;”

- “Adding peak and shoulder bus trips to major routes in the city; and”

- “Looking at options to improve transit mobility along First Avenue.”

Including signal timing adjustment for the existing streetcar lines was surprising, because SDOT has said the mayor is holding up that project, which also would have added transit lanes on Broadway, saving the First Hill Streetcar three minutes southbound. It appears the Center City Connector review prompted a pause on that project too.

The list runs the gambit from no-brainers (free ORCA passes for high school students) to head-scratchers (non-streetcar transit mobility alternatives on First Avenue) to other options that sound good but may not do much, at least without further refinement. Extending transit priority hours on Third Avenue unfortunately hasn’t seemed to significantly modify motorist behavior. A similar flow of scofflaw motorists continue to use Third Avenue despite the new 6am to 7pm prohibition. Moreover, because the restrictions continue to apply only from Stewart Street to S Washington St, private automobile congestion continues to dog buses at either end of the ostensibly transit-only area.

When it comes to making the transit system more pleasant and intuitive, Mayor Durkan has again stood in the way. The Urbanist recently learned that she sent to policy purgatory a proposal to bring modern transit shelters to downtown and South Lake Union streets for free and could raise about $8 million per year in additional revenue, possibly for transit programs like the streetcar. She also has directed SDOT to lay out a reset of the Move Seattle Levy program, which will dramatically water down and possibly cancel promised RapidRide+ projects.

Places where Mayor Durkan’s transportation department had been forging ahead was with a privatized microtransit program that would have primarily benefited wealthy white communities and went against the city’s long-standing commitment to public transit and labor rights. That proposal fizzled out this summer after a broad spectrum of advocates denounced the program.

In short, while Mayor Durkan’s verbal commitment to transit is fairly clear, what’s not clear is the follow through. A Friday newsdump that showed little enthusiasm and positive outlook for the project at hand suggests that the mayor is still agonizing on a project that should get moving, which her own report essentially affirmed.

*Editor’s Note: This article has been edited to indicate the daily numbers are weekday estimates. Ridership projections are usually expressed as weekday numbers. The Urbanist converts annual numbers to weekday estimates by dividing 312 from annual projections.

Owen Pickford

Owen is a solutions engineer for a software company. He has an amateur interest in urban policy, focusing on housing. His primary mode is a bicycle but isn't ashamed of riding down the hill and taking the bus back up. Feel free to tweet at him: @pickovven.