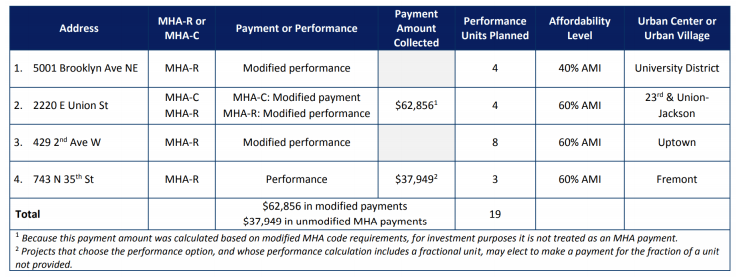

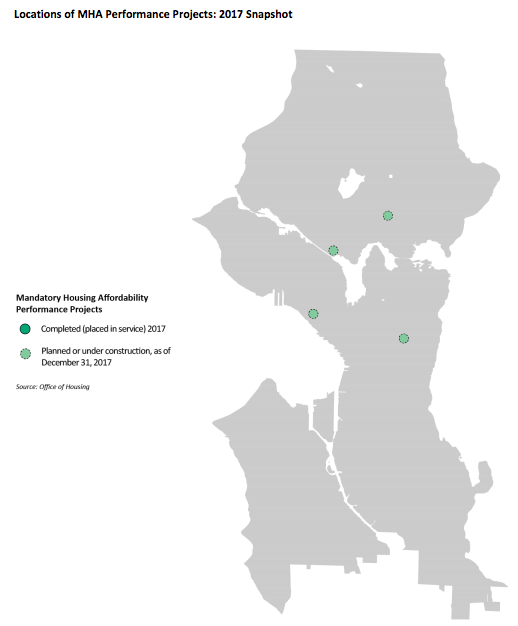

The fruits of Seattle’s mandatory affordable housing program for new development are beginning to bear, albeit it’s still quite early. Last Tuesday, the Seattle Office of Housing (OH) briefed the city council on the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program’s progress to date. OH highlighted four projects that will make affordable housing contributions at or below 60% of the area median income in the next few years–likely in the 2019-2021 timeframe, if they get built. Other projects in the pipeline will soon reach the building permit approval stage at which formal contributions to affordable housing (either through on-site performance or payments to the city) are set and made prior to issuance.

The four projects that OH covered all involved voluntary (contract) rezones by developers rather than areawide legislative rezones that have been going before the city council for approval in the past year (e.g., South Lake Union and University District). The contract rezones are site-specific and tied to a specific development proposal. In each of those cases, developers have reached the building permit stage of their projects and chosen to construct at least some or most of the required affordable housing on-site, which may be an early indication that developers would rather provide affordable units on their properties rather than pay a standard per-square-foot fee to the City instead.

Together, the four projects–all in different geographic areas of the city and all in a designated Urban Village or Urban Center–will result in the construction of 19 affordable housing units (out of 424 units planned for construction), which will provide homes to households making up to 40% or 60% of the area median income, depending upon the project. A further $100,805 has been raised from the two of the projects as payment contributions to the city for affordable housing investments. $62,856 of this was committed last year two to projects in Roosevelt and Chinatown: Uncle Bob’s Place (sponsored by Interim CDA) and Roosevelt TOD (sponsored by Mercy Housing NW and Bellwether Housing). Those contributions will ultimately help construct about one affordable dwelling unit, according to OH staff.

Since most of the contract rezones happened prior to the areawide rezones, setting standardized contribution rates and the implementation of an administrative rule by the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections, the projects are subject to “modified” contribution rates, which are generally less than the rates that have been set or will be set.

Another interesting factor is that the three “modified” payment and performance projects all voluntarily participated in contributions to MHA. Technically, the weren’t legally required to make any contributions as part of their contract rezones since they vested before MHA. However, the city council’s intent in approving the MHA framework and contract rezones was that developers wouldn’t just submit contract rezones to avoid participation in the program.

Emily Alvarado, a program manager for OH, cautioned speculation on the early program results. “If you’re looking for big reporting on what’s happening with MHA so far, it’s still too early,” she said. “The development cycle is such that once the code is in place, it still takes some time before we the see the projects coming through and vesting in this program. If you look outside and you see a crane, that project is already well past the time of coming into MHA.”

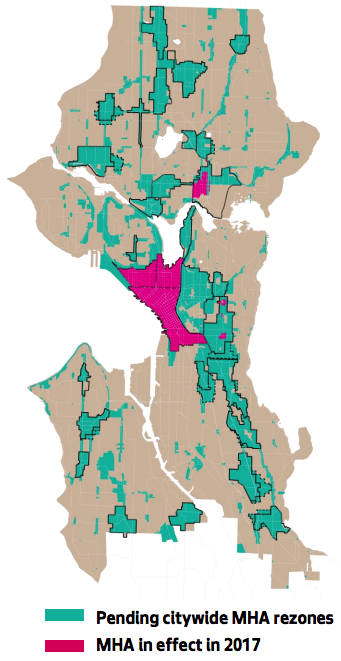

As Alvarado noted, many projects in the development pipeline indeed have vested to older developments codes and are not subject to MHA. The current geographic area of MHA is also fairly small, accounting for districts in Downtown Seattle, South Lake Union, Uptown, Chinatown-International District, Pioneer Square, and the University District. Large swaths of the city, including many Urban Villages and Urban Centers, still remain without MHA zoning and contribution requirements. Projects being proposed in those areas, for now, will continue to be exempt from MHA participation. However, the city council appears intent on passing rezones to implement the requirements, perhaps as early as next year. The implementation schedule has been delayed by an appeal lead by homeowner groups that is still tied up with the Hearing Examiner.

On the flipside, Alvarado indicated that a better picture of the MHA program should soon begin to form where reporting on results may be more useful. “Increasingly, as we move through this year, we will see more and more projects, particularly those from Downtown/South Lake Union and those from the University District be earlier changes and application of MHA will be coming through,” Alvarado said.

Seattle has a much bigger goal for affordable housing production in the mid-term. By 2026, the city hopes that 6,000 affordable housing units will be built under the MHA program, but getting there can’t be done with on-site affordable housing alone. During the briefing, Alvarado vigorously defended the design of the MHA program, which allows developers to pay affordable housing fees to the city instead of building affordable housing. Alvarado addressed this topic in several ways:

- From a financial and affordable housing delivery standpoint, she said that financial contributions from MHA allows OH to leverage an additional two to three dollars in third party financing for affordable housing for every dollar received from monetary MHA contributions.

- There isn’t data to support the assertion that affordable housing integration at the building-level is more meaningful than at the community-level.

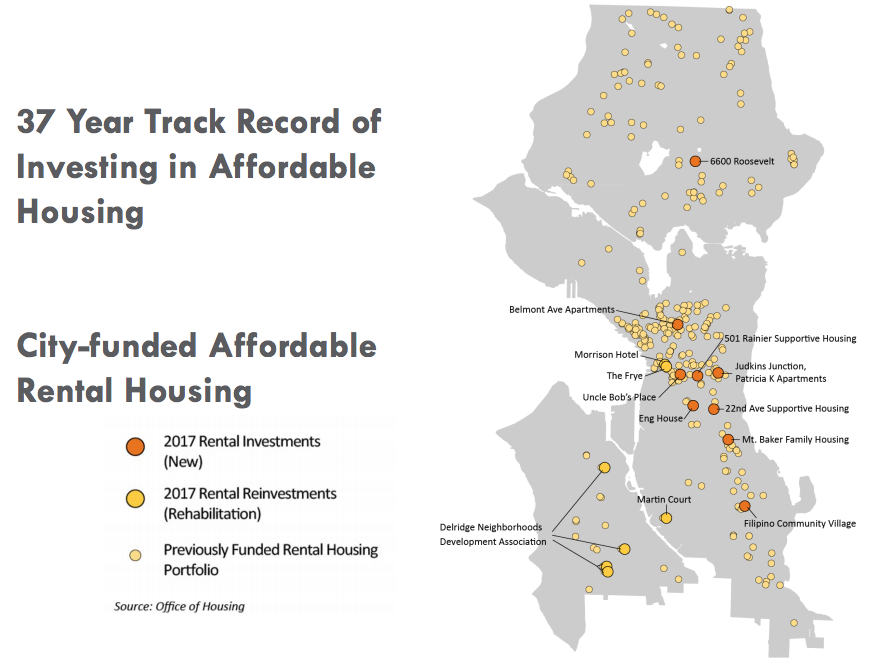

- The city has very specific objectives in the MHA program directing OH to invest monetary contributions in housing projects near high-quality transit, in Urban Centers and Urban Villages, and near where monetary contributions were derived.

- The quality of strictly affordable housing projects is not noticeably different from most market-rate housing developments.

There is a long track record of OH directly investing in affordable housing projects across the city, which Alvarado pointed to during the briefing. Many of these are located in high cost areas of the city. Only a few areas of the city have been missed in prior years. “The places where you see the fewest investments are the places that are presently zoned single-family,” Alvarado said. “Because we invest in multifamily housing, because we invest in higher-density housing, or even in our homeownership which is in townhomes typically, not single-family homes.”

So how will MHA perform over the next decade? It’s still too early to draw any firm conclusions, but the fact that developers are willing to construct on-site affordable units in their market-rate developments should at least dispel the narrative that they never will.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.