On a Thursday evening in early June, at the top floor of King County Metro Transit’s building on South Jackson Street, the One Center City advisory group quietly met after a nine-month hiatus. Notice for the meeting had only been posted to the obscure website for One Center City planning that very morning, and only two members of the public (myself included) were there to watch the meeting. In attendance were the dozen or so members of the advisory group, who represent various downtown neighborhoods and business interests, and high-level staff members for the government agencies involved: Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT), Metro, Sound Transit, and the Downtown Seattle Association.

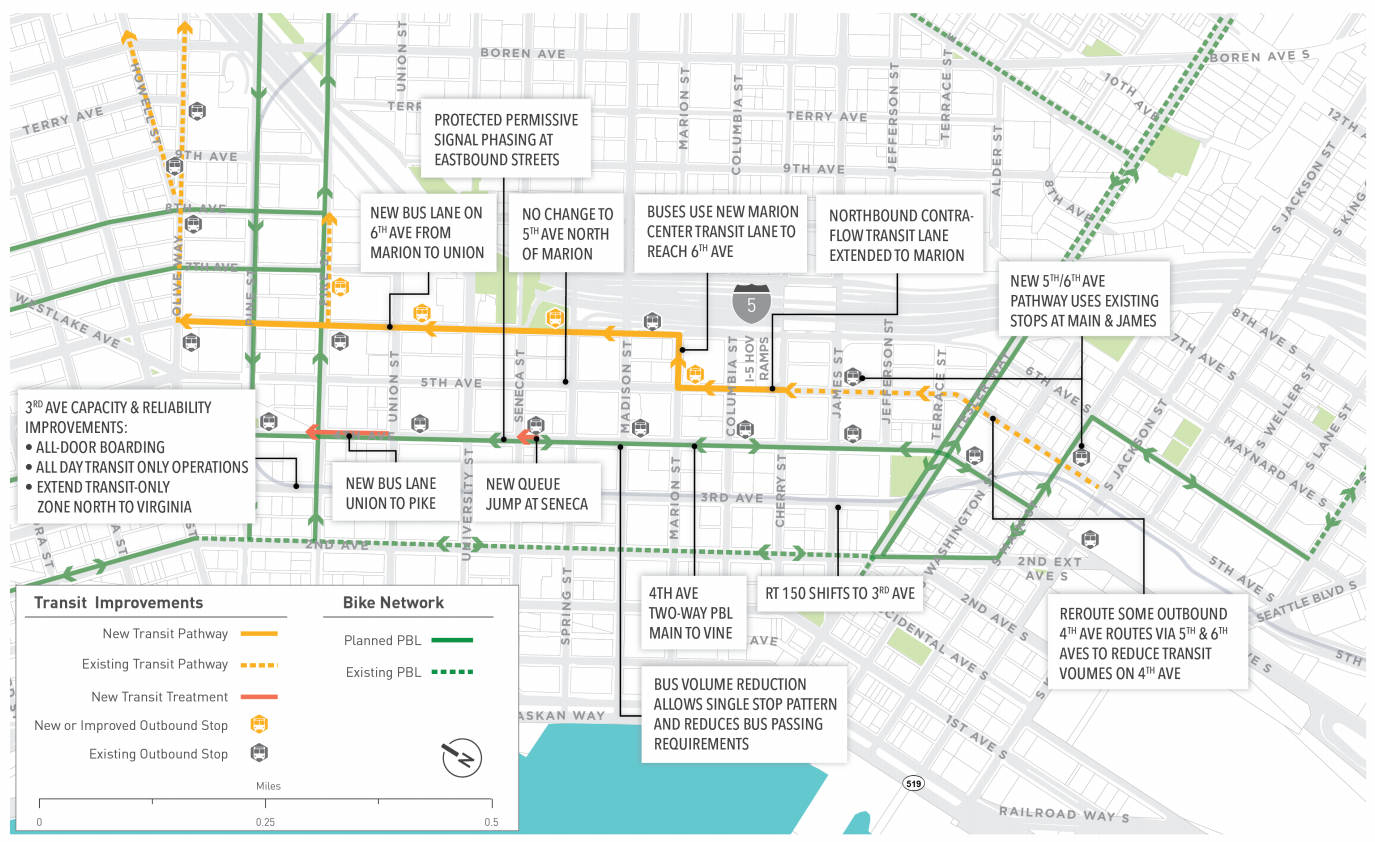

They were there to get a recap of the decisions that had been finalized, without them, during those nine months as Seattle’s new mayor assumed control and the Washington State Convention Center expansion, the pivot point on which so many transportation challenges downtown in the next few years hinge upon, was approved by the city council. In that time, the Fourth Avenue protected bike lane was postponed to 2021, Metro and Sound Transit announced that they would largely not be truncating any bus routes at the University of Washington light rail station to avoid downtown congestion, and SDOT told the city council’s transportation committee that it was far from a sure thing that additional northbound bus lanes on Fifth and Sixth Avenues would be ready in time for the March 2019 exit of buses from the Downtown Seattle Transit Tunnel.

The board also received word that One Center City, closely associated with the “period of maximum constraint” and the specific projects associated with it, would be rebranding: the new name is now “Imagine Downtown: Big Ideas for the Heart of Seattle.” Imagine Downtown will be the umbrella under which the agencies conduct the long-term planning around moving people through Seattle’s central neighborhoods. The fact that Imagine Downtown was also the name for the City of Atlanta’s downtown planning process that completed in 2009 was not mentioned.

The big question is will the long-term plan result is the same outcome as the short-term plan: elected officials pulling out the most palatable segments of the consensus-driven comprehensive project list and abandoning the rest. With the long-term plan, there is not a catalyzing event like the convention center driving the process, so reversion to the status quo is even more likely.

The long-term planning process will occur over the next year or so, with a full report on the recommendations of the advisory board at the end. That process kicks off with the next advisory board meeting next Thursday, July 26th, at 6pm.

At the meeting, the board received a rundown of the projects that ultimately were selected to receive portions of the $30 million in mitigation funds that the transit agencies would be investing in keeping people moving downtown during the period of maximum constraint. It’s worth reviewing what those ended up being.

- Third Avenue transit corridor improvements ($3 million): The Urbanist will be covering those changes in full detail in separate posts, starting with this one last week.

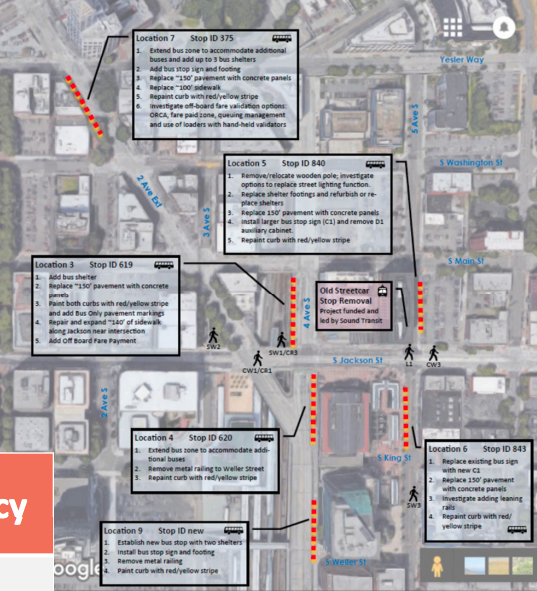

- Improvements around bus stops and key pedestrian corridors International District/Chinatown Station. This includes replacing the terminus of the old Waterfront Streetcar line at 5th Ave S and S Jackson St.

- Public realm improvements around Downtown ($800,000). These improvements are targeting McGraw Square, a key connector between central downtown and Denny Triangle, and the Market to MOHAI public realm improvement plan for areas in Belltown and South Lake Union.

- Pedestrian improvements ($4 million): Includes “enhanced lighting, intersections, wayfinding, trees and sidewalk spot repair and decluttering.” It’s worth noting that many of the improvements to speed up transit, like the ones along Fourth and Second Avenues will do so by adding dedicated turn phases that limit the amount of pedestrian crossing time but may not provide protection from turning movements when people walking have the right-of-way, not doing much to improve safety.

- Second and Fourth Avenues transit improvements ($1.4 million): This mainly comes in the form of a dedicated turn phase where there are no conflicts with pedestrians, clearing the intersection and ensuring that buses more through the corridor faster as general purpose traffic exits turn lanes.

- Fifth and Sixth Avenues transit lanes ($3.2 million): The addition of a northbound transit lane is still in the works through coordination with Washington State Department of Transportation, which must approve changes to streets that directly connect to freeway on and off-ramps. If successful, this will take 28 afternoon peak bus trips off Fourth Avenue, which should make both streets carry more bus riders more efficiently.

- Montlake Triangle Improvements ($5.3 million): With only the Route 255 being considered for reroute to the University of Washington light rail station when the Downtown Seattle Transit Tunnel, which it uses, closes to buses, the transit agencies are still committed to making connections at this station better. SDOT’s interim director Goran Sparrman suggested that Montlake might even be considered as a back up transfer point if traffic becomes much worse than expected during the period of maximum constraint. All-door boarding is also being considered here.

- Traffic and curb management ($3.7 million): under the auspices of “maintaining access for people and goods”, SDOT is committing to streamlining the permit for commercial vehicle permits, expanding the e-park service which informs drivers where parking is available, and to attempt a pilot of alternative urban goods delivery services (like cargo bikes).

- Transit demand management and program expansion ($3.4 million): This continues the work that transportation demand management programs have done to discourage solo driving downtown. SDOT is committing to reducing single occupancy vehicle mode share downtown by 1,200 peak trips this year and an additional 3,000 next year. Strategies to meet this ambitious goal include increasing telecommuting rates, additional investments in transit through the benefit district, and improved last-mile connections from walking and biking. It also includes a contracted transit pilot that the city council has ruled out at the moment, which would have targeted neighborhoods with high drive-alone rates and provided door-to-door shuttle service provided by private companies.

Now that the near-term improvements are set in stone, and One Center City attempts to rebrand itself into something new, it remains to be seen whether the agencies involved will continue to treat the process as one to be handled at arm’s length or one that will be fully embraced.

Let’s Add New Bus Lanes to Overcome ‘Period of Maximum Constraint’

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.