The voter-approved Seattle Transportation Benefit District (STBD) is getting its first big policy reform since the passage of Proposition 1 in 2014. The tax measure was devised as a response to imminent countywide cuts to transit, saving the city from apocalyptic service reductions and eventually allowing for overall transit service expansion.

Though the scope of programs and policy objectives have changed over the past few years, the formal policy changes and district authority that could soon be passed (as soon as next week) Seattle City Council would the pave the way for wider availability of free ORCA transit passes for students, tangible speed and reliability improvements on bus corridors, and service boosts on bus routes that wouldn’t qualify for additional city-funded investments under current law.

Overview of STBD Reform Proposal

To recap, the ordinance authorizes the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) to do the following:

- Regional partnerships. The legislation would expand the opportunity for regional partnerships to cost-share service improvements on routes that only have 65% of stops within Seattle. This would reduce the minimum requirement from 80% of stops within Seattle, allowing many other routes to become eligible for additional service hour investments, including Routes 106, 120, 124, 345, 372, and 373 and the RapidRide E Line–routes that tend to operate in underserved areas of the city.

- RapidRide service. All existing and future RapidRide services would be eligible for additional service hour investments regardless of geographic operation (i.e., wholly or partially operating in Seattle) or performance metrics.

- Capital investments. Through December 2020, SDOT would be able to spend additional revenues on capital improvements for transit. These investments could include transit-only lanes, queue jumps, transit signal priority, and other strategies to improve speed and reliability. Capital investments could also be made to enhance the passenger experience, such as off-board fare payment and stop improvements.

- ORCA transit passes. All Seattle Public Schools high school students (10,200) would received free ORCA transit passes in addition to another 500 middle school students and 300 Seattle Promise community college students. This would be a massive expansion of free transit passes for students in the city. Right now, the city helps fund 3,000 free transit passes for qualifying high school (2,600) and middle school (400) students. Seattle Public Schools provides an additional 8,000 free transit passes to high school (6,200) and middle school (1,800) students. The school district would continue their contributions to funding student passes.

- Contracted pilot transit services. A new pilot program for contracted transit services would be created. Several transit van routes would be set up to provide first-mile/last-mile connections for underserved areas and between other corridors of interest by third-party transit providers–that is, not by King County Metro Transit. Transit vans would be required to provide seating capacity for at least eight passengers. While contractors may not be unionized like most Metro operators, companies would need to provide labor harmony agreements to be eligible as a city contractor.

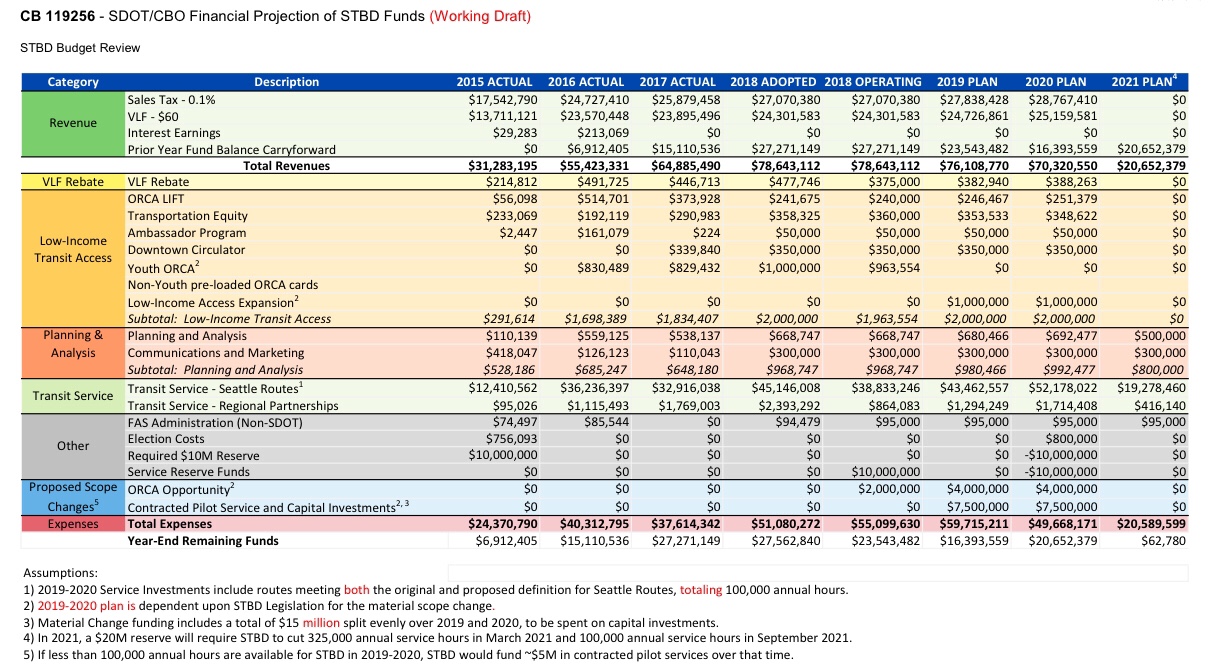

The legislation would impose budget controls on several of the new program areas:

- $7 million annually for the free student ORCA passes (including program management);

- $10 million annually for targeted transit priority and passenger amenity capital investments (through 2020); and

- $5 million annually for contracted pilot transit services.

Creating Lifelong Transit Users at Youth

In a May council meeting, Councilmember Rob Johnson pitched the idea of expanding the free ORCA transit pass for all public primary and secondary students as a way of giving younger children access to more mobility options. SDOT staff poured some cold water on the idea by saying that public schools have a unique cost recovery framework for yellow school bus service with the state. The more students that use them, the greater the cost recovery the school districts can claim, so in the case of Seattle Public Schools, the district may be lukewarm or reticent to change.

Councilmember Johnson acknowledged the state funding pitfall but suggested that just because that’s the prevailing framework now, it shouldn’t hold Seattle back from beginning conversations surrounding the issue. He also suggested that the city should consider lobbying state legislators to reform state law allowing for channeling of yellow school bus subsidies for universal free ORCA transit passes for students instead.

STBD Awash In Money, Not Enough Ways To Spend It

Seattle is in a unique position where the STBD fund balance has a very large surplus–up to $27.2 million but programmed to be drawn down to $23.5 million by end of year. By and large, this is the result of underspending for increased bus service with Metro, but not because SDOT doesn’t want more bus service.

Metro finds itself in a pickle with not enough equipment, operators, and storage capacity to handle more equipment. When SDOT sought a Fall 2018 service increase of 100,000 new annual service hours in the city, Metro responded by promising only 15,000 more–a far cry from SDOT’s ask. Other areas of the county are slated to get service improvements this fall, too, which only adds as a constraining factor–Metro can’t just cater to Seattle.

Expansion of the Atlantic Base is underway and could help with much-needed bus storage space in the near-term, but it won’t be ready until next year and in any case new operators and equipment are still needed, particularly if new service hours are to be deployed at peak travel times.

This has a downstream impact to SDOT since the city is soon to experience a multi-year squeeze in the city center (aka “period of maximum constraint“). Some major construction projects will have significant impacts to surface streets, including the Washington State Convention Center expansion that will give the city a double whammy. Not only will surface streets near the expansion site be influx and clogged, the expansion means that Convention Place Station will close forcing hundreds of buses out of the transit tunnel. This will force buses onto surface streets to operate their routes in the city center and put greater pressure limited on-street layover space. Additional light rail service to ease some of the pain–namely Northgate Link–won’t come online until 2021, so the transit tunnel will remain underused in the interim.

Regional transit operators and SDOT devised a plan to reduce some of the pain by dedicating additional transit lanes and transit priority in the city center and off-board fare payment on Third Avenue. However, the near-term the Center City Connector streetcar project that would have added thousands of extra seats through the city center has been paused indefinitely. SDOT did not recommend a very robust amount of transit-only lanes on additional streets in the city center. And Metro and Sound Transit failed to adopt ambitious bus restructures for cross-lake routes, such as funneling buses to Montlake Triangle to force transfers to light rail and saving both valuable service hours and riders untold delays on city streets.

This perfect storm leaves Seattle with few good choices to expanding transit in the meantime.

Contracted Pilot Transit Services Conundrum

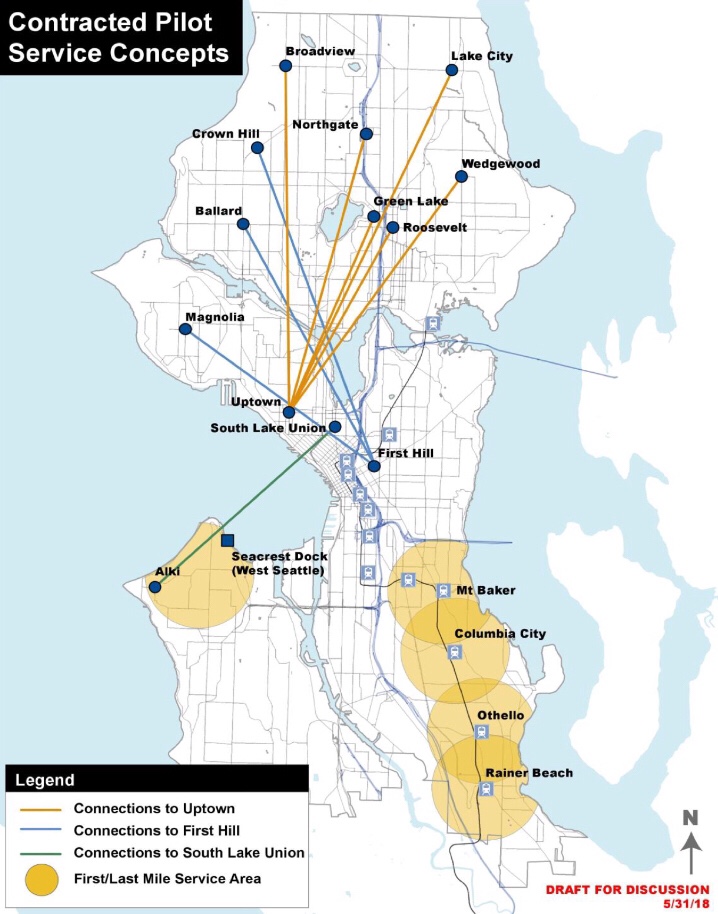

SDOT has whipped up a new pilot program for contracted transit services. Briefing the city council in May and June, SDOT suggested establishing several new fixed transit van routes. Nine routes would operate between outer neighborhoods and Uptown, First, and South Lake Union, presumably as one-seat rides. First-mile/last-mile connections could also be provided to transit riders in South Seattle near light rail stations and the Seacrest Dock in West Seattle. Transit vans would carry at least eight passengers per trip and be operated by private contractor companies, not Metro. The pilot program, however, needs buy-off from the city council, which has tentatively capped the initiative at $5 million annually.

The pilot program was the primary reason for holding the overall STBD reform legislation earlier this month. Some people expressed concerns that SDOT would be using private contractors who would not be unionized. Metro similarly has non-unionized contractors operating transit van services.

In justifying the pilot program, SDOT provided information to the city council on results from the 2017 Commute Mode Split Survey. City data indicates that there are 3,000 commuters that pass through the city center on weekdays that are not well served by transit. The conceptual origin-destination pairs have higher than typical of single-occupancy vehicle (SOV) trip mode split than other city center-bound commuter pairs (around 25%), which SDOT hopes to capture through the pilot program. Rachel VerBoort, an SDOT planner, indicated that SOVs can account from 30% to 60% of all trips for the conceptual origin-destination pairs. VerBoort also said that transit as a choice for these trips is challenging for potential riders because they require one or more transfers, many of which would need to happen in the city center.

Interestingly, some of SDOT’s justification for the pilot program does not appear to match the outlined concepts presented to the city council. Only one of the conceptual origin-destination pairs passes through the city center, that being between Alki to South Lake Union. A second pair between Magnolia and First Hill is a marginal case, but in all likelihood people driving are avoiding downtown streets. Some of the first-mile/last-mile trips to core transit routes, however, might be able to pick up some of the slack for people driving on downtown streets. If the objective is to eliminate a sizable portion of the 3,000 SOV trips from downtown streets, then it is not clear that the long-distance origin-destination pairs would remotely achieve that.

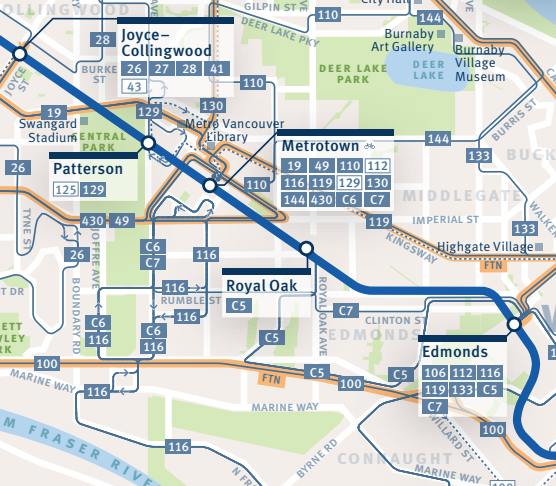

In Vancouver, British Columbia, TransLink operates a robust network of regular transit vans known as “Community Shuttles” that connect to SkyTrain and key elements of the frequent, high-capacity bus network. Metro locally offers a similar type of service for smaller communities, such as DART and Community Connections shuttles (fixed and semi-flexible routes) in addition to ACCESS (flexible routes for accessibility), but has yet to be deployed on the same scale of Vancouver. In many cases, local densities, geography, and roadways can make it difficult to properly service or justify full-fledged 40- and 60-foot bus service. Seattle is no different, particularly with the chosen first-mile/last-mile concepts in Southeast Seattle and West Seattle. Several transit van services could do the job better and more comprehensively than regular fixed route service.

A major hurdle to the entire contracted pilot transit service program is state preemption law. SDOT would have to gain approval from Metro before any new contracted transit route could legally launch. That may not necessarily be a substantial issue given that SDOT is already coordinating with Metro anyway for service integration, including the use of ORCA for fare payment, but there is still the off-chance that Metro could deny the request. Ideally, SDOT would use the same contractors that Metro does for ACCESS, DART, and Community Connection transit van routes (these buses are operated by private contractors, but transit vans are official equipment in the Metro fleet) so that they can be folded into the Metro portfolio instead of creating more discontinuity in transit administration.

It may be advisable that SDOT should scratch its concept for the long-distance origin-destination routes and instead focus exclusively on first-mile/last-mile challenges leaving backbone high-capacity transit routes to do the real transit job.

But a bigger win for transit riders may simply be adding more to the capital investments bucket. Money poured into expanding off-board fare payment throughout Downtown Seattle, adding transit-only and business access transit lanes on targeted corridors, and installing more transit signal priority and queue jumps could save thousands of service hours per year in perpetuity, likely delivering more collective benefits than any ongoing contracted pilot transit service program would. Put another away, the travel time savings could be immense to riders, allow Metro to operate more trips, and encourage much higher ridership overall.

Title image courtesy of King County.

Let’s Add New Bus Lanes to Overcome ‘Period of Maximum Constraint’

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.