Last week, the Seattle Monorail released a study detailing strategies to upgrade the monorail from tourist attraction to an integral rapid, high-capacity transit line. VIA Architecture, a local design and planning firm, was commissioned for the job and suggests that three phases of strategic investments be made in the coming years. The cost for the full suite of improvements is relatively affordable with no more than $25 million needed to double overall capacity.

The case for the Seattle Monorail is actually quite good. Third Avenue is already running near capacity, buses lack the kind of grade separation that the monorail offers, and there is only two stops on the monorail. As a result, the monorail is able to traverse the distance from Westlake to Seattle Center in 1.5 minutes while buses on Third Avenue take upward of 10 minutes on average to reach the heart of Uptown/Seattle Center. And while frequency between the monorail and Third Avenue-operating buses is about the same between the two districts, service reliability is vastly better than the buses. The monorail boasts nearly 100% on-time performance where buses are running around 87%.

Right now, the monorail has an hourly capacity of 3,000 riders per hour per direction, amounting to 6,000 riders per hour. The study suggests that hourly capacity could be increased to 12,000 riders per hour (6,000 riders per hour per direction) if several strategic changes are implemented. This would be incredibly useful once the Seattle Center Arena is renovated and becomes home to several more sports franchises, offering a fast way to shuttle transit riders between light rail, streetcar, and buses operating from the Westlake area.

Actual usage of the monorail today, however, is closer to 5,500 daily riders, which is far below the potential capacity.

There are several big impediments to ridership:

- The monorail lacks ORCA transit pass integration. The city and Seattle Monorail are actively working on ORCA integration, which could be functional later this year.

- When the mall at Westlake was built, the monorail station and guideway was moved limiting the flow of trains and boarding process. Planners want to partially right this by dramatically reforming platform operations at Westlake. There are also recommendations to improvement passenger flows at Seattle Center.

- Similarly, station access and visibility is challenge for both monorail stations, but particularly at Westlake. The study recommends major station access improvements.

- The location at Seattle Center is challenging because it places riders near the middle of a civic center instead of in the middle of Uptown. More job, housing, and institutional growth closer to the edges of Seattle Center–particularly east of 5th Ave N–could naturally improve ridership demand in addition to a refurbished Seattle Center Arena. Movement of the station, however, is basically out of the question since it would be prohibitively expensive.

- Trains cannot loop at the end of the line. Therefore, trains are limited to operating on their single guideway rails.

Westlake Station Concept

The study contemplates two phases of improvements to the Westlake monorail station. The first phase would involve very modest changes to improvement passenger flows and move to automated fare payment. The second phase would primarily be focused on giving passengers better access to the station.

- Phase 1: The study suggests that an empty retail space just beyond the ticket booth could be removed to provide better access and loading area to the station platforms. Gates at the platforms and the ticket booth could also be removed. With removal of these features, the overall platform area could be further extended into the mall. Ticket vending machines would be installed near the Saks Off Fifth store wall and faregates just beyond them to access the platforms. Keeping the platforms flowing is a key objective with the changes, and a simple way to ensure that passengers board and alight trains properly would involve placing marked queuing and train exiting decals on the platform pavement.

- Phase 2: Passengers currently have to enter into the mall and use interior stairs, escalators, or elevators to reach the platforms, which is somewhat confusing and time consumptive. The study suggests making a more direct connection to street-level from the Pine Street frontage. Storage areas and a retail space south of the station area would be removed and in their place a new public walkway corridor would be constructed. Exterior stair and an elevator would be built to connect with the new walkway corridor, making it much easier for passengers to reach the station. Additionally, there would be changes to the mezzanine level in the Downtown Seattle Transit Tunnel, which would include some minor demolition of walls and an elevator to the monorail station.

The first phase would cost under $3.9 million, and the second around $9.2 million in 2018 dollars.

Seattle Center Station Concept

Three phases of improvements to the Seattle Center stations are recommended by the study. The first would make basic operational improvements changes for fare payment and boarding followed by two rounds of deeper visual connection and accessibility improvements through ramps and stairs.

- Phase 1: Faregates and ticket vending machines would be introduced in this phase, removing the need for ticket booths. Level boarding at platforms and automated gates at the edge of the platforms would be provided to enhance safety and accessibility. The boarding and alighting process would also change.

- Phase 2: This phase is focused on several access improvements for passengers. A new elevator would be built to provide direct access to the station and ground level. To improve overall passenger flows, a new covered entrance with stairs and a ramp would be constructed at the south end of the station, which should help with peak ridership times and queuing.

- Phase 3: This last phase would provide more access options north of the station. It would similarly provide an entrance coupled with stairs and ramps for queuing and accessibility.

The first phase would cost around $3.1 million in 2018 dollars. The second and third phases would come in under $6.9 million in total.

Belltown Infill Station Concept

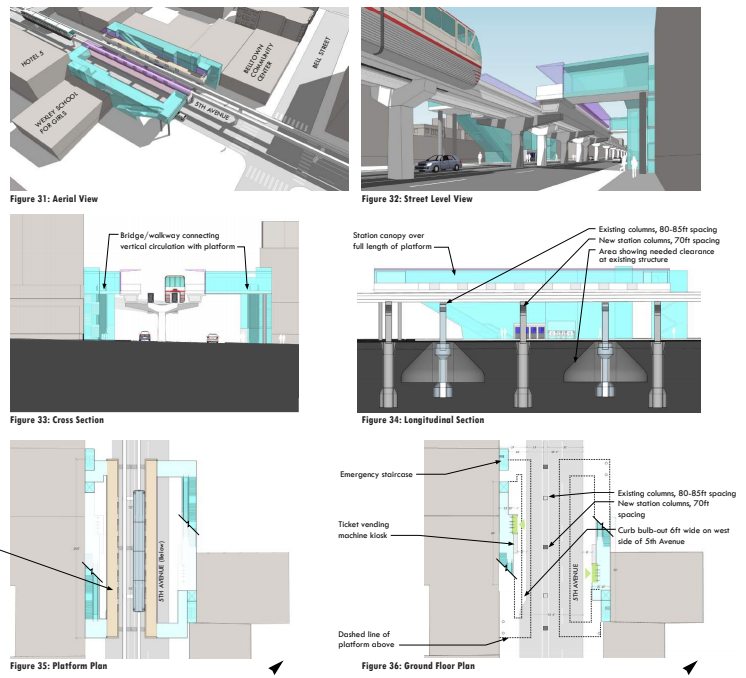

The study suggests a future infill station in Belltown, perhaps around Bell Street. VIA Architecture indicates that the station could be technically feasible. The additional time associated with the stop could add about four to six minutes to roundtrips, planners suggest. The implication of this is reduced frequency and thereby capacity, which could affect overall demand and particularly depress ridership on game days at Seattle Center Arena (assuming trains are running full). However, the infill station would offer additional utility for riders heading to and from Westlake or Seattle Center, perhaps bolstering general ridership. A location on Fifth Avenue at Bell Street also fits well with bus service which operates on Battery Street, Bell Street, Blanchard Street, and Third Avenue.

VIA Architecture provided general schematics of what the infill station could look like and how it would fit within the Fifth Avenue right-of-way. The space is fairly tight given the rails, platform requirements, sidewalks, and station access elements. It’s not suggested in the study, but if this is a desirable thing to accommodate near Bell Street, it would be wise for city officials to reserve right-of-way or build in incentives to facilitate the station through the Land Use Code.

The study highlighted several other concepts considered in the review process, such as an additional platform at Westlake and station at McGraw Square. However, these concepts were removed from recommendation. If the monorail gets new life through the concepts still on the table, it could be welcome news for transit riders and more widely provide a real rapid transit option to the regional transit system.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.