Seattle’s system of sidewalks are worth an estimated $5.6 billion dollars, making them an asset with few equals on the city’s ledgers. But Seattle has neglected its sidewalks for decades and decades, both in terms of expansion and maintenance. The lack of sidewalks in vast swaths of the city–particularly in the extreme north and south ends–is a clear equity issue since those areas also are some of the most racially diverse and low-income parts of the city. The dearth of funds when compared to the colossal scale of the problem generally makes any effort to make a difference look like a silly half-attempt.

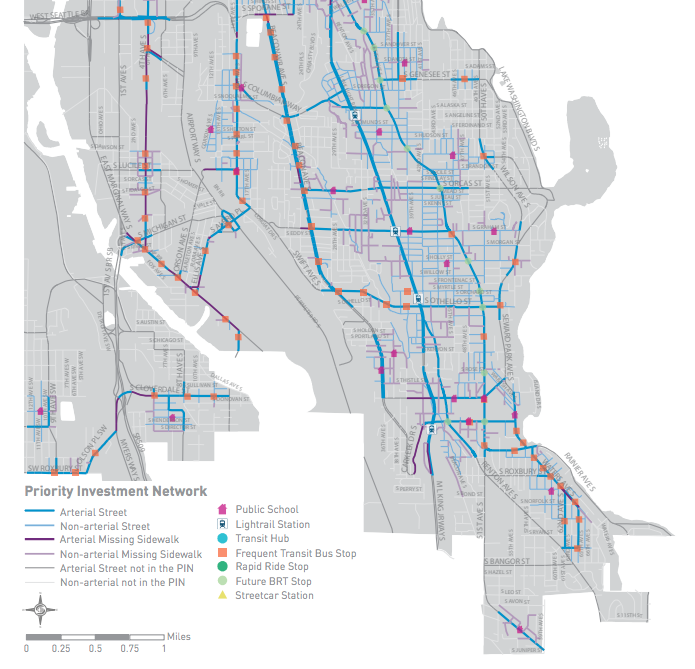

Consider that over the life of our entire nine-year Bridging the Gap levy (from 2007 to 2015) we constructed 118 block faces (one side of one four-sided block) of sidewalks, while the pedestrian master plan estimates that there are still nearly 12,000 blockfaces missing sidewalks, including 1,800 blocks of arterial streets. Simply building missing sidewalks along arterials would require enough concrete to build a straight sidewalk between Seattle and the Vancouver, B.C. suburbs.

The Move Seattle levy was supposed to take a big bite out of the sidewalk deficit. When the Seattle City Council passed legislation authorizing the new nine-year levy to go onto the ballot in November 2015, it included a goal of 150 additional blocks of sidewalks, only a few dozen more than the previous one. But the pressure to deliver more sidewalks to underserved areas of the city led the city to investigate other options under the umbrella of “low cost sidewalks.” As a result, the target of added sidewalk blocks was raised to 250 with no addition to the $61 million in levy funds that were to be allocated to the program. We wrote about this ambitious scale-up at the time, but in the context that we have now in retrospect, it looks like this plan may have been overly ambitious.

As with several other of the subprograms in the levy, rising construction costs during the record building boom and decreased federal matching dollars are wilting the overly rosy projections. Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) remains optimistic about being able to complete the mix of 250 blocks of low-cost and traditional sidewalks by the end of 2024. But the exact ratio of how many blocks will be concrete sidewalks along arterials and how many will be lower cost pathways in arterials is something SDOT staff are now bringing up during the Move Seattle reset discussion.

In the first two years of the levy (2016 and 2017), SDOT has constructed 50 blocks of sidewalks. Of these, only 21 were traditional and 29 were low-cost. The combined cost of these blocks was $12.5 million. With the caveat that the total program expenditure does include some outside overhead separate from the actual project cost, costs per block are coming in at around $248,500 per blockface. This is around the level needed to hit that 250 block goal. However, if 150 of the blocks are going to be traditional sidewalks, SDOT will need to pick up the pace. Thus far, the Move Seattle levy has built 10 or so traditional blocks, but we should be closer to 17 to keep pace. But building a greater share of traditional sidewalks would likely bring costs too high. In other words, now is the time to choose whether to invest in targeted investments to sidewalks on arterials or if we want to keep expanding our scope to the larger areas of our city without sidewalks and put down more blockfaces.

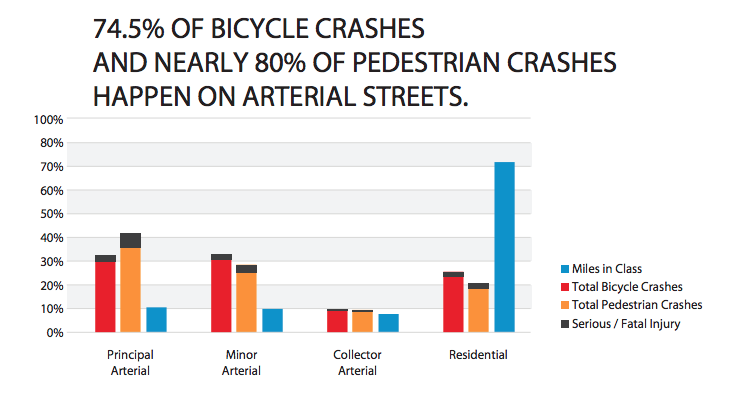

Why are arterials important? The data (specifically the nine-year bike and pedestrian safety analysis conducted by the department several years ago) shows that pedestrians are exponentially more likely to be involved in a collision if they are on an arterial, where traffic speeds are much higher and where pedestrian traffic in a city tends to be concentrated–mirroring transit service and amenities. Pedestrian traffic doesn’t disappear when an arterial is missing a sidewalk for a block or two, increasing the likelihood of a collision.

The choices revolving around sidewalk construction are a little more subtle than the ones around bike lanes or transit corridors, but the decisions we make now will have just as profound an impact on the city’s decisions for the next 10 years. Focusing on a pedestrian master plan agenda that puts vision zero at the top of the desired outcomes is a necessity.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.