The disappointment that urbanists feel about Seattle’s failure to obtain a subway system in 1968 (see part one and part two of the Forward Thrust series) reminds me of… professional sports: the aspirations and the disappointment; the recrimination and lost opportunities; the parsing over stats and precinct data for clues about where the team went wrong… the search for moral victories.

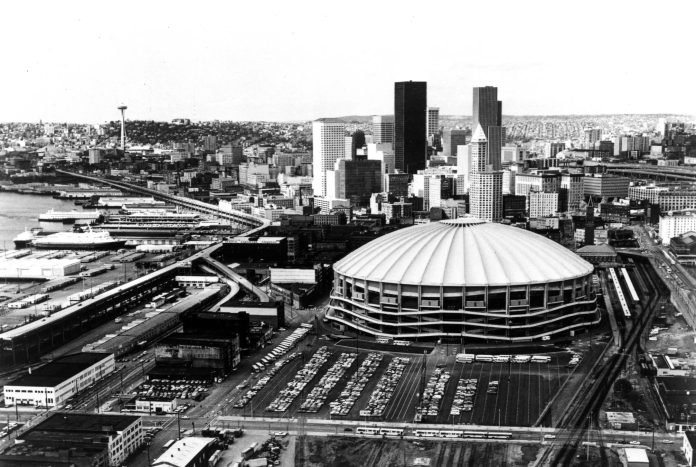

Under normal circumstances, a parallel like this would be crass. Insulting, even. Rapid transit impacts neighborhoods, jobs, health outcomes…lives. Professional sports are largely an escapist fantasy. But in the case of the 1968 Forward Thrust bond initiatives, the comparison is warranted. Because while civic mastermind Jim Ellis and the Forward Thrust committee failed to pass a $2.8 billion (adjusted for inflation) transportation levy that would have left the region with 47 miles of mass transit, they succeeded in getting King County voters to bight on the $293 million (inflation adjusted) multi-purpose arena known as the Kingdome. The 62-38 vote on “County Proposition 2” of Forward Thrust paved the way for the arrival of the Seattle Seahawks (1976) and Seattle Mariners (1977), who both played in the Kingdome for the next quarter century.

The demise of Forward Thrust’s transit initiatives in 1968 and 1970 meant that Seattle’s transit history lags behind the standard set in the 1960s by cities like San Francisco, Portland, and Washington D.C. Between 1966 and 1969, each of these cities posited rapid transit as an answer to questions posed by the explosive growth and environmental hazards of post-WWII capitalism. Like savvy general managers anticipating the crunch of the salary cap, the electorates in those cities made hard political choices well before the appointed hour arrived to make them. These roster moves helped them outpace rivals in towns with less foresight. Towns like Seattle in 1968.

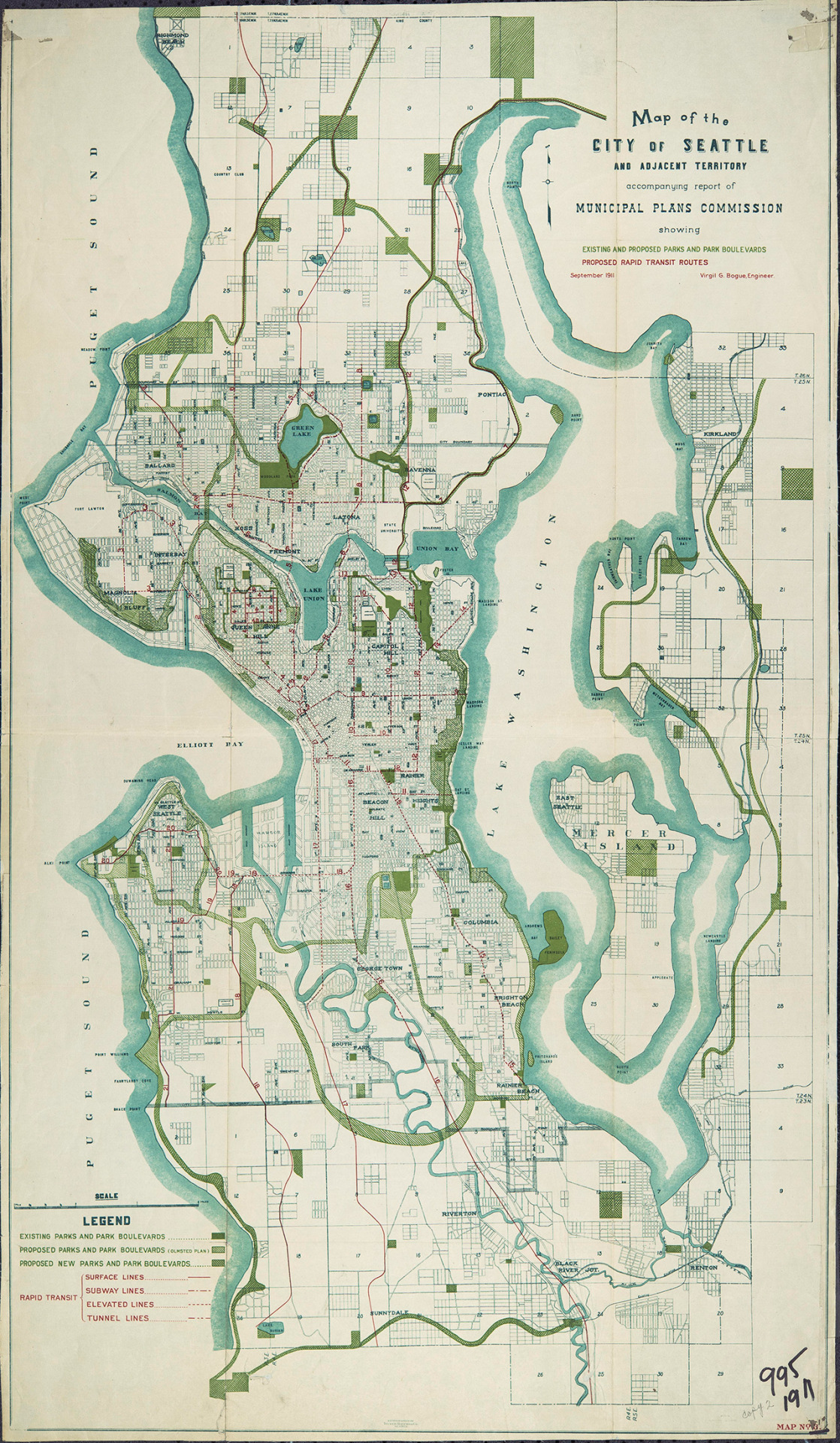

For all its reputation as an environmentally conscious city, Seattle was mired in transit mediocrity for nearly a century. After Seattle voters rejected “The Bogue Plan” and its 90 miles of comprehensive citywide transit in 1912 and then turned down Forward Thrust’s rail initiatives in 1968 and 1970, Seattle finally opened its relatively piddling 14-mile light rail system in July 2009 after a Sound Transit measure for it passed in 1996. If city transit systems were ESPN Power Rankings, Seattle was somewhere near the bottom of the list of big-league cities for close to 100 years.

It’s hard to say whether the Mariners or the Seahawks are a better metaphor for Seattle transit history. The Mariners and existential underachievement have gone hand-in-hand for the entirety of the franchise’s history, leading one to conclude that Seattle can’t have nice things because of some unfixable regional hex or an inexorable symbolic curse. And like Forward Thrust in the late 1960s, a doubleheader of success and failure has stalked the Seahawks since the mid-2010s, when the deliverance of one Super Bowl was dashed by the disappointment of the next. While it is unfair to look out at the thousands of acres of public parks Forward Thrust left behind and call it a “failure,” it is also impossible to discuss Forward Thrust without exorcising the specter of what could have been.

Forward Thrust and professional sports—urbanism and civic athletics—are joined at the hip. The highs and lows of one reinforce the aspirations and disappointments of the other. Children of the same era, they’re repositories for all the same civic urges that make people want to congregate in American cities.

What Seattleites can’t achieve in their politics, they have a way of sublimating into their sports.

##

The story of how the Seahawks and Mariners came to Seattle is the story of businessmen and their proxy politicians who manipulated city politics behind the scenes. They circumvented the outward-facing political process until the last possible second, at which point they asked the public to go into hundreds of millions of dollars of debt to pay for a facility that would further enrich those same businessmen. In his seminal 1976 history text Seattle: Past to Present, Roger Sale wrote “in the big leagues, money and power play rough.” In the case of Forward Thrust, they also played cunningly:

The Washington State legislative session before the Forward Thrust vote of February 1968 saw legislators who endorsed Forward Thrust grease the skids of state government to serve the project. This effort entailed the advent of seventeen separate state bills that either enhanced Forward Thrust’s chance of electoral success or made its core measures legally feasible. Among them were:

- S.B. 505, which authorized cities in Washington State to construct stadium facilities, and created a revenue source all potential stadia with a 2% excise tax on hotel profits.

- And S.B. 270, which raised King County’s borrowing limit from 5% to 10% of the county’s total assessed property value, and extended the duration of county bond limits from 30 years to 40 years.

These measures allowed the county to go into deeper and longer debt so that a city therein could build a stadium; the construction of this stadium would be more likely to be approved by voters since the debt required to build it would be spread out over a longer period, and would be partially reimbursed by a tax subsidy. Forward Thrust researcher Suzanne Vandenbosch has written that “it does not seem likely that many voters were aware that these bills were under consideration.” Nonetheless, they all passed. As a result of the precedent set by S.B. 270, the debt for the Kingdome—finally paid off in 2015—outlived the Kingdome itself by 15 years.

The team comprising Forward Thrust’s legislative offensive line was not a rag-tag group of loveable losers, but a powerful conglomerate of capitalists. An April 1968 issue of Seattle Magazine provided a power map of “The Seattle Establishment,” placing Forward Thrust mastermind Jim Ellis in the number one slot, and most of his business and political associates on the Forward Thrust committee closely behind him. Ellis was also a partner in one of two financial firms in Seattle that was large enough to sell the massive municipal bonds needed to finance Forward Thrust—an electoral slate of 11 bond measures totaling $5.8 billion of debt. To put it crudely, Ellis was a Visa salesman who tried and largely succeeded, in getting the public to accept the gaudy terms of a sexy credit card with a high spending limit.

In fairness, Jim Ellis’ motivations for stewarding Forward Thrust sprang from a deep sense of personal responsibility. This is described stirringly in Matthew Klingle’s 2009 book Emerald City: An Environmental History of Seattle as arising partially from survivor’s guilt after his brother died in combat in World War II. At the same time, the traceable profit motive leading from the political activism of Forward Thrust to Jim Ellis’ personal finances was not a good optic. It hurt the Forward Thrust ballot initiatives politically. The editor of The Washington Teamster—which had over 35,000 readers in King County in the late 1960s—asked “here’s the question that has been bugging me,” in November 1967; “what legal firm will write up the $5 million bonding fee for the [transit measure]? Will it be Jim Ellis’?”

What we were seeing in this convex of sport and civic debt was a phenomenon described by Jason Hackworth in The Neoliberal City: Governance, Ideology, and Development in American Urbanism. It was the creation of a system of financialization where, in the words of Hackworth, “cities are vulnerable to the decisions of capital market gatekeepers because they are dependent on debt.” Forward Thrust heralded the erection of massive financial arbiters like Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch, who determine the creditworthiness of whole American cities, standing between them and the capital they need to fund improvement projects and basic services. The prerequisite for this debt dependency is an unwillingness to pursue other, progressive streams of revenue, like taxes on high income, inheritance, and financial services transactions.

The many businessmen on the Forward Thrust committee did not suggest taxing themselves to pay for the Forward Thrust ballot initiatives. And the politicians who endorsed Forward Thrust in the state legislature did not re-write state law to allow municipalities to pursue more progressive streams of revenue. A dream of Washington progressives and leftists since The Great Depression, a high-earners’ income tax would have been every bit as impactful for future generations as a mass transit package. But instead, Forward Thrust re-wrote state laws to allow counties the privilege of taking on more and more debt.

Forward Thrust was a harbinger of the slow cancellation of the Keynesian capitalist consensus that funded a strong welfare state and social entitlements with various redistributive mechanisms. As the 70s arrived, that status quo was replaced by neoliberalism—a guise of capitalism defined by pro-business policies that pervade the public commons, upwardly redistributing all of the resulting wealth while downwardly redistributing the costs of creating wealth.

Seattle’s transit policy lagged behind other American cities in 1968. But in sports, it was ahead of the curve. Because while many histories of American urbanism date the rise of neoliberalism at New York City’s budget crisis of the mid-1970s, Seattle and Forward Thrust were already experimenting with neoliberal governance a decade earlier:

A cohort of politicians secretly jigger state laws under the influence of an elite business establishment before presenting the public with an omnibus of debt that would privately enrich their cronies. That sounds more like a political machination of the Koch Brothers in 2018 than of Seattle moderates in 1968. Forward Thrust walked this path for the benevolent goal of public transit (and the seemingly benign pursuit of pro-sports); but that shouldn’t distract from the fact that it was a largely supra-governmental approach to public life that made government an instrument for private ends.

Forward Thrust was the first inning of the neoliberal long game, played well before anyone quite knew the rules.

##

In his 2010 book Bad Sports: How Owners Are Ruining The Games We Love, sportswriter Dave Zirin details a litany of examples where sports became a venue for private profit and civic extortion. In New York City in the 2000s, George Steinbrenner threatened to move the New York Yankees to New Jersey or Connecticut in order to secure $850 million in public bonds for the construction of a new Yankee Stadium that opened in 2009. In Minnesota, Twins owner Carl Pohlad lined the pockets of area politicians until they bully-balled a regressive sales tax through local government to help fund a $500 million stadium that broke ground in 2007. In Washington D.C in 2006, Mayor Anthony Williams jammed a $611 million tax hike through the city council to fund a new baseball stadium, in a city that had the highest poverty and infant mortality rates in the nation.

Forward Thrust anticipated each of these incidents by forty years, parlaying Seattle’s anxieties about remaining a second-tier town into making its electorate go into generational debt to finance the Kingdome in 1968. In his 2013 book Becoming Big League: Seattle, the Pilots, and Stadium Politics, Bill Mullins wrote that “Seattleites who pushed for a new stadium were less concerned about [its] financial impact and more attracted to the prestige of becoming a big-league city.” And yet economics and emotion went hand-in-hand, as politicians like King County Executive John Spellman pitched the Kingdome as a “job creator” that could help lift the region out of a torrid early 1970s recession.

Even as they are themselves often unaccountable, sports are supposed to provide fans an escape from the ups and downs of an unaccountable economy. The iteration of the Seahawks spanning 2012-2017 did their part to deliver on the promise of Forward Thrust, gifting Seattle fans six exemplary years of football in which the team was annually among the most consistently competitive in the league. With the team’s logo harkening back to the indigenous tribes that first stewarded the land the franchise represents, and many of its players taking stands against the galloping inequalities of American life, the Seahawks resonated with Seattleites of color in ways that Forward Thrust failed to when it was soliciting votes for its transit initiative.

The architects of Forward Thrust aspired to a blandly universal urbanism that was impressive because of the grand sweep of its ideas, but wanting for impassioned specificity. The failure of Forward Thrust’s transit initiative to inspire passion—not just support, but passion—from its base may account for much of its failure to pass.

Conservatives of various kinds never lose touch with their sense of indignation, because it has a simple root: that times change. Since time only moves in one direction, these groups will always have something to oppose, and will be constantly aggrieved in a way that can be measured in political energy expended, votes cast, candidates elected. The broadly defined Left—a group that ought to include urbanists who think equitable, easily navigable cities are a site for human liberation—are not always so easily ignited. It’s harder to impress upon voters that things can change than it is to tell voters to oppose change; as a result, visionaries in search of big new projects seem ever on the electoral defensive against people whose political modus operandi is to just say no.

But herein lies a way in which professional sports—for all their faults—can imply something greater than their sordid foundations. Looking out at the seas of Seahawks fans in the aforementioned golden age of 2012-2017, one is struck by what is possible when masses of people begin to believe that something is possible. The futile years of Seahawks history—which rival and even exceed those of the hapless Mariners—suddenly seemed to matter less in their playoff runs than the determination of the team to end them.

For better and worse, sports remain one of the few avenues of public life where masses are allowed to imagine together; where the virtues of collective action are performed and praised. We cheer for these teams because, somewhere in there, we’ve all found ourselves.

The featured Kingdome and Seattle skyline image is courtesy of the Seattle Municipal Archives.

Shaun Scott

Shaun Scott is a Seattle writer. His book Heartbreak City is available wherever books are sold.