Cape Town’s Day Zero, the day that most water taps in the city will be turned off, has been pushed back to 2019, but the name remains ominous enough. Day Zero. Simultaneously the day of nothing and the day of a new era. Cape Town’s water crisis connects it to cities around the world. A water crisis can result from too much or not, sometimes both at the same time. Large sections of Jakarta and New Orleans are already below sea-level, and the resulting problems will only escalate as sea levels continue to rise in the coming decades. Bangkok is a heavy city on sinking land, and the ominous photos of flooding from 2011 start to seem more like visions of the future rather than documentation of a historic crisis. Water crises are not limited to seaside cities, either. Mexico City is a mile and a half above sea level, but its water crisis is visible just from walking around the streets, seen in the structures tilting out over the sidewalks due to subsidence.

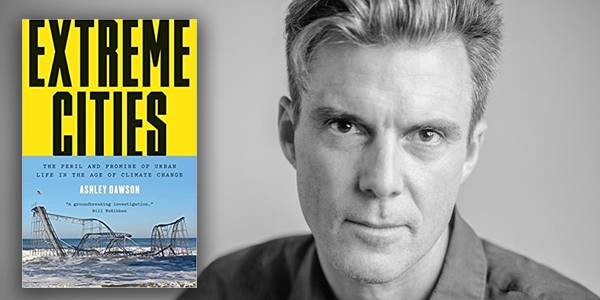

In Extreme Cities, published last year by Verso Books, Ashley Dawson explores possible futures for the city in the flood and heat of climate change. He sees the city as an ignored nexus of climate change, the location of many of its most turbulent results, and the site where much of its damage will be incurred. “The city is paradoxically the greatest expression, principal culprit, and most endangered artifact of our turbulent times,” he writes. Urbanist manifestos promote the city, against the suburbs and the country, as dense and efficient paradises. Dawson’s version of the city is something different. As the principal culprit of climate change, cities are responsible for massive amounts of energy consumption and pollution. The relative savings from density are overshadowed by absolute waste.

The catch is that there’s nothing equal about waste production and energy use, both on a global level and urban level. Just two percent of New York City’s buildings use forty-five percent of its energy. When Dawson imagines climate change, one of his concerns is that present inequalities not be carried into urban futures. It’s appealing to think that a widespread disaster might create a surge of collective activity, and a just redistribution of wealth, but there are no guarantees. The future might just as easily exacerbate the present inequalities. “If natural disasters potentially open a communist horizon,” he writes, “the reconstruction process also offers an opportunity for elites to recapture and even intensify their power.”

In considering the redistributive potential of disaster, Dawson turns to New York after Hurricane Sandy. In response to Naomi Klein’s concept of disaster capitalism, private profit from collective crisis, he explores disaster communism. It’s a useful account for a number of reasons. The narratives we consume of disaster often consist of survivors squabbling over diminished resources. Dawson replaces this with a vision of survivors helping each other through crisis. Dawson’s account of the hurricane suggests that while the city is often marked by cruelty, competition, and violence, it also functions through a largely unnoticed web of cooperation.

Dawson is skeptical of the recent tendency in urban design to speak of resilience. The trouble with resilience is that it has little to say about the many. It repeats the conservative fantasy of the elite few who sustain themselves against the many, and attends to symptoms rather than addressing the conditions that produce crises. While disaster communism might be an example of resilience that sustains the many rather than the few, Dawson notes that local acts of aid and resistance do not “actually constitute an inherent threat to the capitalist social order” (253). The prime example of resilience for Dawson is capitalism itself, which has shown a remarkable ability to survive against disasters, crises, and a hundred and fifty years of prophecies predicting its imminent collapse.

One optimistic response to climate change is the promise of technology. But much of Extreme Cities demonstrates that there is no technological fix for many of climate change’s threats to cities. Dykes may protect cities in the Netherlands, but they would be useless in Miami. Built on porous limestone, a barricaded Miami would still flood as water seeped up through the bedrock. In southern Florida, seawalls would function only as a trap that promises safety while doing little to mitigate disaster or, in some cases, even exacerbate the problem once it arrives. Dawson proposes retreat, not from the city in general but from cities that cannot be sustained, specifically including cities of southern California and Florida. The question is not finally one of whether retreat will take place, but “under what conditions this retreat will take place.” One of the examples here is the Isle de Jean Charles Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Indians who have begun resettlement away from the Louisiana coast as their land is eaten away. For Dawson, any sort of resettlement should be built around moving communities, rather than dispersing individuals, and must be voluntary to avoid repeating histories of forced dispossession, migration, and climate apartheid.

The world is full of legends of floods that destroy empires, or sink continents, or exterminate most of humanity, and these possibilities are built into our current narrative of climate change. But part of our current problem is what literary critic Rob Nixon has described as slow violence. The causes and effects of climate change are dispersed over time and space. By the end of the book, Dawson raises the specter of human extinction, and it is imperative to see these two problems in relation to each other. The species and its cities are both at risk unless we learn to pay attention to a slow seeping upwards and crumbling inwards.

Ashley Dawson will speak about “Extreme Cities” at 5pm Sunday, May 6, as part of Red May Seattle. Tickets are $5.

The featured image of the Atlantic City waterfront after Hurricane Sandy was used by Verso Books in Extreme Cities’ cover art.