Most of us have an attic, or a storage locker, or a closet, or a drawer that is neglected, full of things that we don’t pay attention to. Out of sight, out of mind.

Cities have those too, areas where needs, infrastructure, and services are neglected, areas that exist outside of the city’s focus. Neglected areas attract less city and private investment. Property values are lower and rents are cheaper. Those who can’t afford property or rents in other locations migrate there: blue collar hard-working families, young new families, immigrant communities and people of color, and transient communities. All are affected by the neglected infrastructure and its lack of safety, but none are affected more than the most vulnerable. Out of sight, out of mind.

The northern end of Seattle’s Aurora Avenue N. is one of those neglected areas. Follow Aurora out past South Lake Union, Queen Anne, Fremont, and Wallingford to an often–overlooked stretch of Aurora that extends from the north edge of Woodland Park at N. 59th Street to Seattle’s city limits at N. 145th Street.

This stretch of Aurora slices through the heart of two urban villages, the Aurora-Licton Springs Residential Urban Village and the Bitter Lake Hub Urban Village. In EACH average year 197 people are injured and one killed along its length. These aren’t just dry statistics. They are people with faces like those of your family, faces who live, work, shop, and go to school along its length. Aurora and many of the faces you’d meet along it are profiled in a series “Along the Mother Road” that KUOW radio is producing.

Take a look at the toll of crashes, injuries, and deaths along that 4.3 miles long stretch of Aurora in the last 10 years. In those same 10 years Seattle lost three opportunities to make things better and safer.

Aurora from N. 145th St. to N. 59th St. from January 2008 thru March 2018:

-

- 3,516 crashes (343 per year)

-

- 11 people killed (1 per year)

-

- 2,020 injuries (197 per year)

-

- 183 pedestrians hit (18 per year)

- 51 bicycles hit (5 per year)

- Average 80 crashes per mile each year. (Statistics from SDOT collision database as compiled here.)

In 2008 the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) and the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) partnered and secured funds for a makeover of Seattle’s Aurora. At the same time the city of Shoreline partnered with WSDOT and others to do the same in Shoreline. Some of the less far-sighted auto-oriented businesses in both cities objected and appealed. The City of Seattle relented … the funds that had been earmarked for Aurora were spent elsewhere. The city of Shoreline persevered and today in Shoreline you can see the safer, more humane, and more thriving results.

In 2015 as part of the advertising for the Move Seattle levy the Aurora Corridor was listed as one of the needs to be addressed by the levy. In spite of Move Seattle’s success at the polls, nothing ever came of Aurora … its promised improvements vanished. Out of sight, out of mind.

In the summer of 2018 WSDOT plans to repave Aurora from Roy Street near the tunnel to the city limits at N. 145th Street. WSDOT is responsible for the paved part of the roadway between the curbs, SDOT is responsible for everything within the right-of-way outside of the curbs, including the sidewalks and the median. WSDOT asked SDOT whether they would like to partner with them and include more extensive safety and livability improvements during the repaving. SDOT said no.

People at Risk: Bitter Lake Hub Urban Village

Aurora is a road serving much of the wealth in Seattle at its south end in South Lake Union. But the other end of Aurora, the north end, is the opposite. It’s the forgotten end. Out of sight, out of mind.

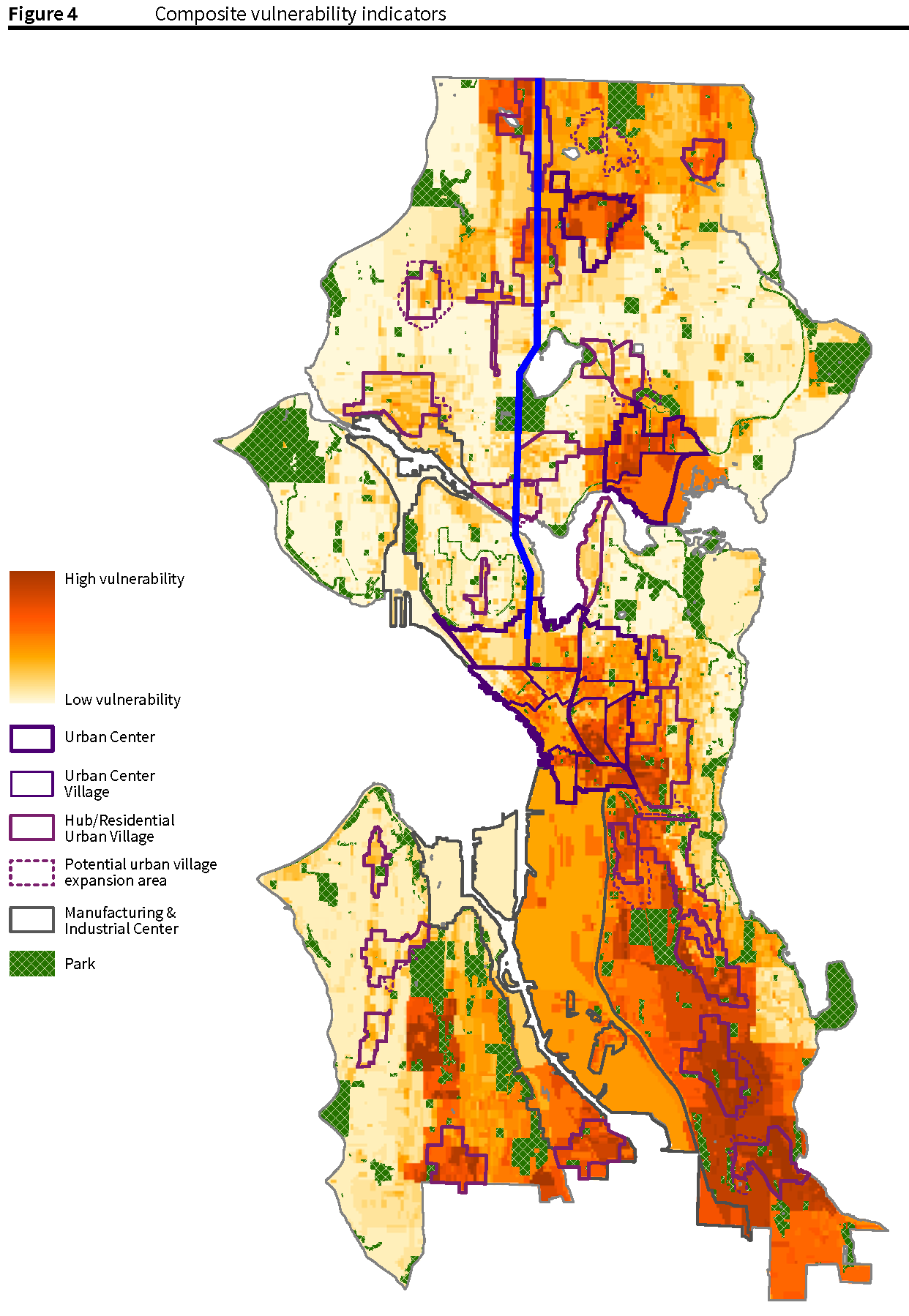

The Seattle 2035 Comprehensive Plan’s Growth and Equity section contains the following map of vulnerability indicators. The people along the Aurora corridor (Aurora is superimposed in blue) are progressively more vulnerable towards its northern end.

The demographics underlying 2035 Seattle and the preceding map are in large part drawn from the 2010 census. Much has changed since 2010. Many young families and economically challenged people in Seattle have been forced to the north and to the south from the more costly and more central parts of the city. Large multi-story affordable housing complexes for families and for the elderly have been built, and are continuing to be built, within one block of northern Aurora.

78% of its students qualified for free or reduced-cost lunches …

Seattle Public School’s school reports provide a glimpse of the socio-economic, ethnic, and immigration characteristics of each school’s neighborhoods. The elementary school serving the east side of Aurora In the Bitter Lake Urban Village is Northgate Elementary. As of October 2016 78% of its students qualified for free or reduced-cost lunches. 81% were children of color. 42% were English language learners.

The elementary school serving the west side of Aurora in the same area is Broadview-Thomson K-8. 58% of its elementary students qualified for free or reduced-cost lunches. 68% were children of color. 29% were English language learners.

Those students, predominantly disadvantaged, must risk their way across and along one of the most dangerous streets in Seattle to and from school, shopping, activities, and home – a major arterial that for the most part has no sidewalks.

Do you need to walk or bike between the Bitter Lake and Licton Springs Urban Villages?

Many middle school students who live in Bitter Lake or Haller Lake do need to walk bike, or bus to and from Robert Eagle Staff Middle School on N. 90th Street in the Aurora-Licton Springs Urban Village. Aurora is the only connection the three quarters of a mile between Meridian and Fremont Avenues.

They have a choice: Walk or bike in the mud along the west side of Aurora.

Or walk or bike along the east side of Aurora and squeeze between the overgrown hedge, the power poles, the curb, and busses scurrying by at 30 miles per hour in the bus lane an elbow-width away.

Main Street in the Aurora-Licton Springs Urban Village

Aurora is a repellent gash through what should be the heart of the Aurora Licton Springs Residential Urban Village. It is a barrier separating adjacent neighborhoods. The city’s neglect forces people away from what could be a vibrant Main Street. Like many neglected back alleys, Aurora breeds deterioration and attracts crime. Out of sight, out of mind.

Compare with Lake City Way, near N 125th Street. Like Aurora, Lake City Way is a state highway. It carries more traffic than Aurora carries through the Aurora-Licton Springs Urban Village. It was retrofitted to better serve the people who live, work, and shop along it with some of the money transferred from the Aurora Corridor project that was cancelled in 2008. This area of Seattle’s Lake City is now thriving with a mix of new residential and pre-existing and new neighborhood retail.

Or compare Aurora in north Seattle with Aurora in Shoreline. In 2008, when Seattle cancelled its Aurora project, Shoreline proceeded with theirs. Shoreline’s Aurora is now a thriving and successful mix of residential, retail, and pre-existing auto-oriented commercial along a much safer and more pleasant Main Street.

Importantly, Seattle’s neglect of Aurora is not merely a transportation issue.

It is too important to be left solely to transportation planners. It is a safety issue for all who use Aurora. It is an equity issue for those underserved who must risk walking on its shoulders. And it is a city planning issue affecting all who live, work, go to school, or pass through Aurora’s neighborhoods. Out of sight, out of mind.

The neglect of Aurora deteriorates surrounding neighborhoods and makes them less livable. With vision Aurora could be a key opportunity in developing additional affordable housing along the busiest Rapid–Ride bus route in the City.

The city’s neglect of Aurora is fundamentally a city planning and city vision issue. It will take vision and imagination to tackle it.

An abdication of fundamental city planning.

Seattle’s repeated neglect of civic investment in Aurora is an abdication of fundamental city planning. And it is an abysmal failure of transportation and safety planning. The past 10 years of lost opportunities are a denial of Seattle 2035 growth strategy, equity, and the city’s comprehensive plan.

Improvement won’t happen unless we decide to make it happen.

It will take a coordinated investment by citizens, businesses, the City, and the State requiring:

-

- Proactive city planning and Design Guidelines

-

- Economic development planning

- Transportation and road planning

It’s time for Seattle to stop its willful neglect of Aurora. It’s time for Seattle to regain the opportunities that north Seattle’s Main Street presents.

Lee Bruch is a retired architect and project manager. In the mid 1970’s he was an architect involved in the City of Vancouver, BC’s Phase 1 False Creek Development, which demonstrated how a few people’s visions can turn a neglected area into one of the prides of the city. Since moving to Seattle’s Green Lake area 30 years ago he has watched much of Aurora languish unchanged amidst its lost opportunities.