One of the gifts of living in a large city is the presence of well-endowed cultural institutions. Sitting next to our theater companies, the opera house, and the symphony–perhaps a little higher–is the Seattle Art Museum. True to its elevated position among the city’s institutions, SAM has hosted a number of admirable exhibits in the last few years but its latest, Figuring History, is something special. Returning from the third floor, where you will find the exhibit, I stopped on the second to take a look at the permanent collections, particularly the Minimalist paintings. These paintings could not be more different in their philosophy–antithetical, even–than the works upstairs.

The Figuring History exhibit (showing until May 13th) follows the popular Kerry James Marshall retrospective exhibited in Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles in 2016 and 2017. This exhibit places Kerry James Marshall next to two other Black American painters, Robert Colescott and Mickalene Thomas, whose work, to hastily sum it up, reimagines the canon of Western painting as if it were not dominated by White men portraying White subjects. Instead, by placing Black people or Black places in familiar poses or settings from western painting, rich but marginalized histories are elevated, exceed even the originals they reference and, in the process, give the old works new juice just by association. As Marshall puts it in a videotaped monologue that plays on loop at the museum,

“I never think of the paintings I make as self-expression. I think of them exclusively as platforms for an idea since the idea of representation is really interesting to me. I make a lot of work that’s about that idea. And then I’m also interested in how you reference culture and history in pictures.”

It’s a really rewarding experience and I’d recommend anyone buy a ticket (or sneak in if the ticket price is outside your means).

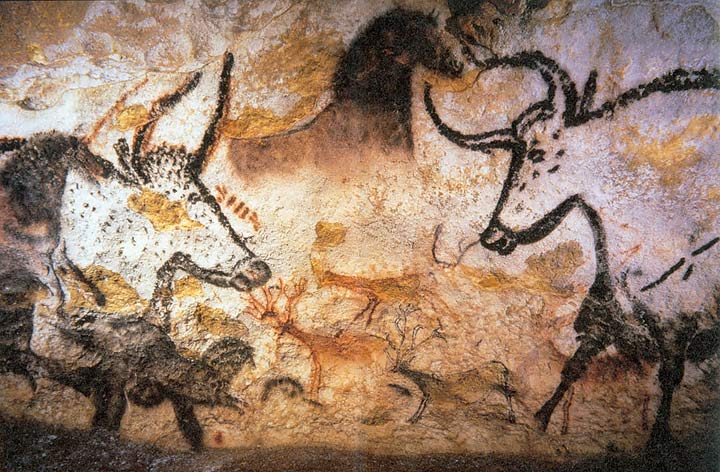

As the Marshall quote above makes clear, his paintings are about representation of history and culture. All art is about something. Even the earliest art is not just a thing, it is a thing about a thing1: the cave paintings in Lascaux, France

…or the Venus of Willendorf

Down the escalator from the Figuring History exhibit is the modern and contemporary art mainly housed in the Wright Gallery. The 20th Century was a wild one and there’s a lot of evocative work in here from expressionism to a giant black rat poised over a bed like a night hag. In a room adjacent to the night rat, and dating to the period beginning in the 1960s, are examples from Minimalist art. An information plaque helps explain the style:

“…’The gesture on the canvas was a gesture of liberation, from Value–political, aesthetic, moral.’ Subsequently, abstraction became a vast realm of possibility: some artists flooded the field of vision with large planes of color. Others limited their palette to white, gray and black to emphasize texture and line, and still others framed the relationship of painting to architecture.”

In the way the cave paintings are about animal hunts and venus carvings are about fertility, Minimalist painting is about painting. By looking inward and examining itself, Minimalist paintings can ask such questions as: canvas–what is it?, oil paint–what is it?, Cartesian shapes–what are they? My first contention is these are not very interesting questions and they certainly are not interesting enough to have placed Minimalist painting in the high position in art institutions and art markets where it sits today.

I could be accused of being a Philistine here. But I don’t think your kid can paint a Jackson Pollock and I think the subject of Duchamp’s urinal–art and authorship–is interesting even after the object that raised those questions has long lost its potency.

The 1960s was a period of tremendous cultural change and political agitation: Vietnam, Betty Friedan, MLK Jr., Malcolm X, Cesar Chavez, the free speech movement, riots, sexual liberation, mutually assured destruction, Presidential assassination. It’s an a capella Billy Joel song to talk about the decade this way but the list of historic events and figures remain impressive no matter how many drug store magazines and Oliver Stone movies revisit it.

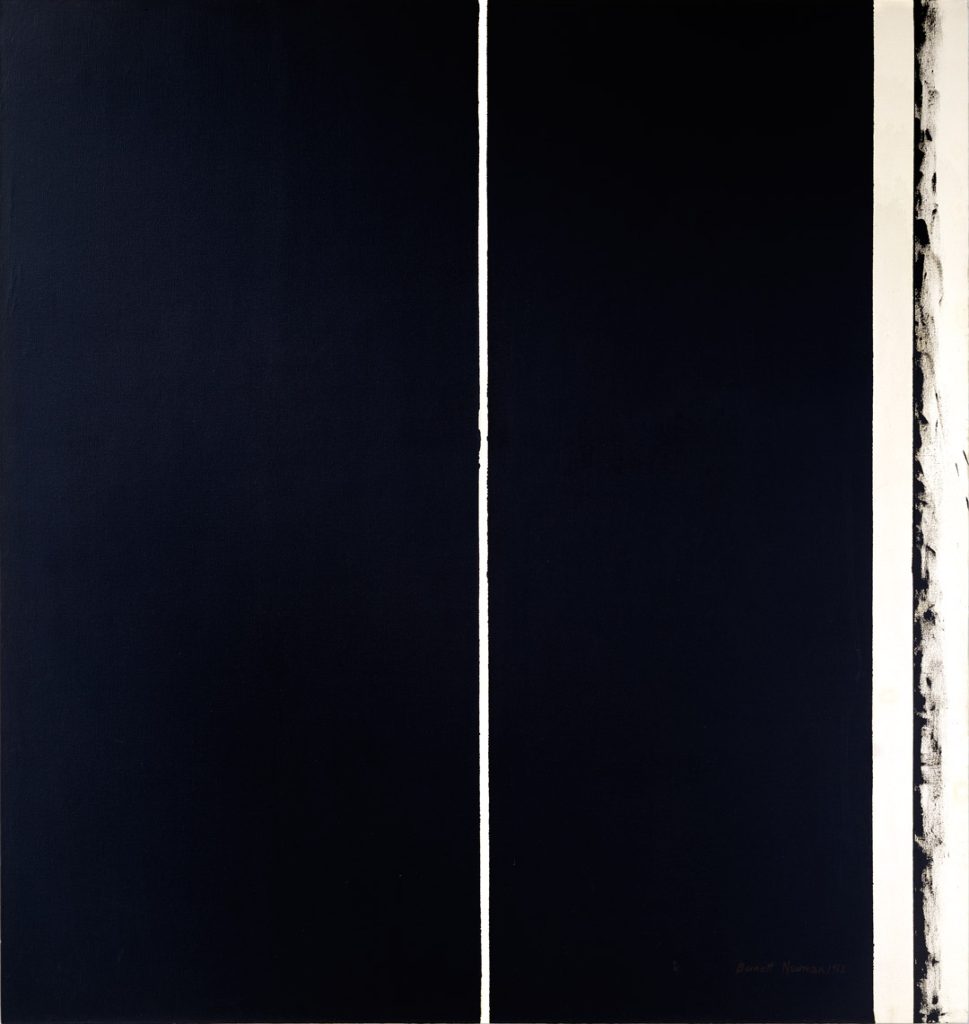

During this dramatic decade Barnett Newman painted The Three which hangs in the Seattle Art Museum today.

Minimalist painting is not just an artifact of art history. It doesn’t just hang in museums as an instructive counterpoint to abstract expressionism or a (superficial) example of the Modernist Project. It maintains its relevance by commanding financial rewards in the art market. In 2014 Barnett Newman’s Black Fire I sold at auction for $84 million, the third highest sale of a painting that year after a Gauguin and a Rothko. The 1960s is also the decade when Colescott, one of the featured artists in Figuring History, got his career started with a solo show in a Portland, Oregon gallery featuring regional artists.

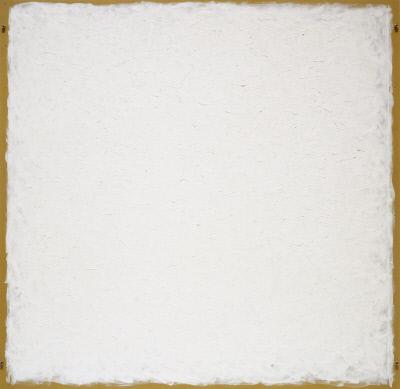

In between the origins of Minimalist paintings and that $84 million sale, paintings in this style continued to take their place in art institutions. Here’s Robert Ryman’s Reagan-era Associate also to be found at the Seattle Art Museum:

The museum website describes his work: “Ryman’s singular format draws attention to the basal elements of painting: the physical aspects of the paint; the manner in which it is applied; the color and texture of the paint support; the attachment of the painted square to the wall.”

The 1980s is also the decade when Marshall, perhaps the star of the Figuring History exhibit, began putting on solo shows near his art school in Southern California. His first touring retrospective was in 2016. Ryman’s was in 1993, the year Marshall painted De Style (not included in the Figuring History exhibit)

The vibrant, relevant, rewarding works of Colescott, Marshall, and Thomas now occupy the same space as the minimalist paintings in the Wright Gallery.

After Figuring History, looking at the Minimalist paintings from the permanent collection–diligently investigating squares, lines, and oil paint texture–I see them in a new light. They look self-indulgent, feckless, suspiciously apolitical, and, maybe worst of all, boring.

Museum space is a precious resource and one we all pay for by covering the tax breaks received by corporations and very wealthy individuals for their donations to these public institutions. What other artists that had something important–or beautiful or terrifying–to say over the last half century not had a chance to say it because Minimalist painting, so sanctified by institutions and critics and markets, sucked all the oxygen out of the room?

The conflict between Figuring History and Minimalist painting isn’t just an unresolved problem of the past. Earlier this year the chief curator of the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art was fired by the museum director, a “highly unusual” move according to the LA Times art critic. The chief curator, Helen Molesworth, hosted the Kerry James Marshall exhibit as it toured the country in 2017. The director, said to have a conflict of vision with Molesworth, chose to show a retrospective of Minimalist sculptor2 Carl Andre that same year. It looked like this:

In an analysis of the the market value of solo exhibits at the Museum of Contemporary Art before and after Molesworth’s appointment, Artnet’s Felix Salmon highlights the symbiotic relationship between art museums and the art market,

“Trustees and big-name art collectors, after all, tend to collect (and, therefore, want to see exhibited) the kind of expensive art, mostly by white men, that Molesworth explicitly tried to move away from. More generally, they like to see the value of their market-friendly collections ratified with prestigious museum shows. Once you’ve spent millions of dollars on a certain artist’s work, you generally want museums to reinforce what your art advisor and your dealer have been telling you, which is that the artist in question is a great genius worthy of being preserved for posterity.”

Figuring History doesn’t just make us re-examine the subjects and settings of European art, it makes us re-examine why some art is canonized in museums and auction houses while other art is lucky to wait for overdue exposure. The Seattle Art Museum and future institutions exhibiting these works can do something now to make that interrogation easier through museum labels or placing the works nearer each other. The layers of drywall that separates Figuring History from the Wright Gallery need to come down.

1.Yes, the ready-made (think: Duchamp’s signed urinal), mechanical reproduction, and time-based art have all complicated notions of object, subject, and their relationship but to the extent that a thing makes us ask the question “is this art?” and makes us enthusiastically respond, “Yes! This is art,” the object and subject relationship is maintained… otherwise it’s just a thing in the world that, at best, does something useful or looks nice.

2. I’ve chosen to focus on Minimalist painting in this article because you can see it while visiting the Figuring History exhibit and it uses the same medium. One could make the case that Minimalist sculpture deserves some re-examination too. I don’t disagree but at least the subjects Minimalist sculpture explores is space and material which, I feel confident saying, are a lot more interesting subjects than canvas and oil paints.

Making Space For Culture: 5 Takeaways From Seattle’s CAP Report

Michael Goldman

Michael works as a real estate valuation analyst. He graduated from the University of Washington with a Masters in Urban Planning and a specialization in real estate. Before Serial broke the long-form true crime scene wide open, he had a podcast about pet adoption.