Yesterday Mayor Jenny Durkan came out in support of road pricing aimed at decongesting traffic in Downtown Seattle and delayed implementation of key Basic Bike Network elements until 2021. The mayor’s announcement comes on the heels of her pausing the Center City Connector streetcar project Friday.

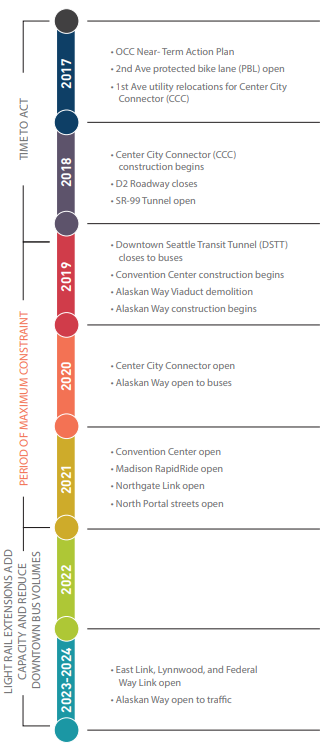

Pausing the streetcar and protected bike lane projects seems to signify a watering down of One Center City, which had included them as near-term recommendations to deal with worsening downtown gridlock anticipated due to a number of major constructions projects and buses coming out of the transit tunnel and spilling onto already congested bus lanes.

During last year’s budget proceedings, Councilmember Mike O’Brien sought and secured $200,000 to study decongestion pricing. The SR-99 tunnel set to open later this year will have tolls–though the state Transportation Commission hasn’t yet decided exactly when tolling will start and how much it’ll charge. One reason Councilmember O’Brien sought decongestion pricing is to discourage motorists seeking to avoid the tunnel toll from funneling onto Downtown streets instead. Another reason–which Mayor Durkan highlighted–is decreasing greenhouse gas emissions–fully two thirds of Seattle’s emissions are from the transportation sector. Decongestion pricing would reduce the number of private vehicles Downtown and ensure traffic moves more efficiently.

Both Mayor Jenny Durkan and her opponent Cary Moon supported exploring decongestion pricing during their campaigns last year. The mayor’s announcement signals support for Councilmember O’Brien effort but didn’t offer much in the way of what her preferred plan would look like. Here’s what we do know about where she stands on One Center City:

Mayor Durkan’s press release suggests many pieces are in flux as her administration searches for “innovative” solutions.

“Engaging both private and public partners, the City is aiming to use every innovative and effective tool, including incentivizing telecommuting, partnering with navigation applications to provide insights on best times to leave downtown, working with local business partners on ‘stay and play’ promotions to encourage commuters to leave downtown at the most beneficial time, and supporting innovative options for first and last mile transit trips such as bike share, microtransit, and carpooling apps,” Mayor Durkan said.

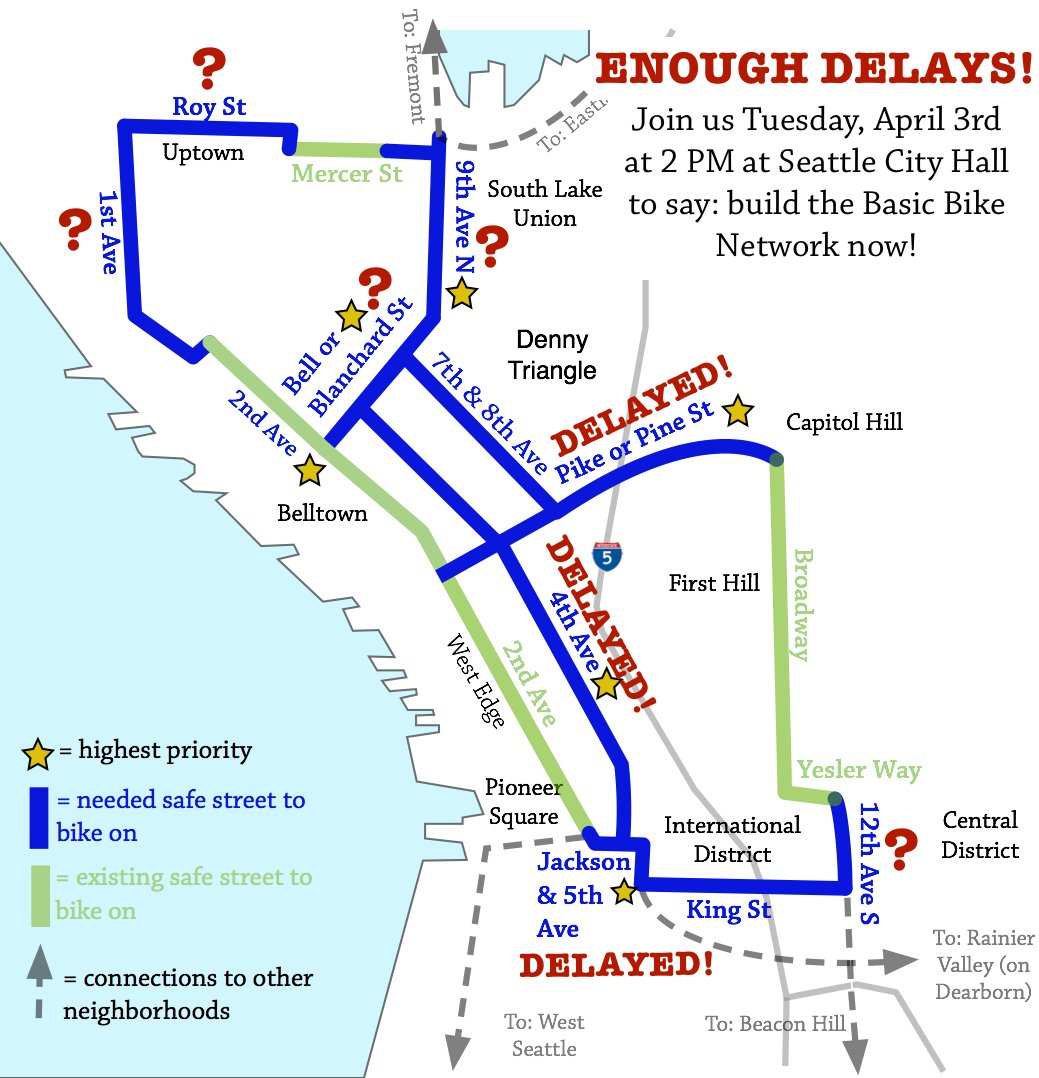

Basic Bike Network Delays

While seeking microsolutions like microtransit and god-from-the-app-machine fixes, the Durkan administration backed away from several near-term recommendations from the One Center City Advisory Board.

- Fourth Avenue protected bike lanes are pushed back to 2021.

- Extending Pike/Pike protected bike lane to Broadway is pushed to 2021, too.

- Ditto Ninth Avenue N protected bike lanes.

- The Center City Connector streetcar was assumed in planning but with Durkan’s executive stop-work order, its future is now uncertain and it may not open until 2021 (or later) if work is resumed.

One Center City Near-Term Actions

The City and its partners affirmed some One Center City elements:

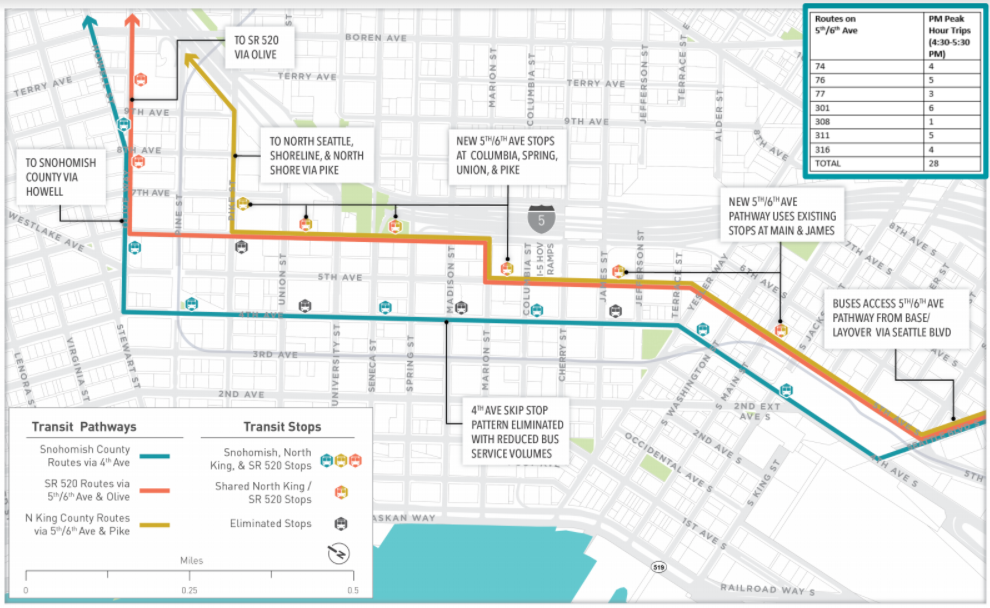

- The transitway on Fifth and Sixth Avenues is slotted for September 2019.

- Third Avenue will get all-door boarding and presumably off-board payment by September 2019.

- Public Realm improvements (e.g., enhanced bus stops, better lighting, and safer street crossings) in Downtown, Chinatown-International District, and Montlake Triangle.

- On the other hand, improved “user experience” for pedestrians will include yet more signage cluttering sidewalk. The statement promises improved “wayfinding for motorists looking for parking to reduce circling and congestion” is also promised.”

- Ridehailing zones at transit stations judging by the promise of “enhancing transit stops to help travelers find a ridehail or carshare vehicle to complete their trip.”

The One Center City partners–the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT), King County Metro Transit, Sound Transit, Seattle Office of Planning and Community Development, and the Downtown Seattle Association–define the period of maximum constraint from 2019 to 2021. Since key protected bike lanes are pushed back to 2021, they are not a part of the strategy to deal with this constrained period. In fact, it would appear SDOT has again sacrificed bike lanes on the altar of preserving level of service for motor vehicles, which they can rationalize since it means transit will move a little faster.

Transportation Committee Chair O’Brien and Councilmember Rob Johnson expressed frustration at being left out of the loop regarding One Center City changes at Tuesday’s committee meeting. SDOT Interim Director Goran Sparrman said delaying protected bike lanes give the Downtown transportation network “resiliency” in the period of maximum constraint. Councilmember Johnson lamented how poorly allocated Downtown street space is, and he has a point. Protected bike lanes rank highly for people-moving capacity per square foot of street space, and on-street parking ranks lowest of all, yet we see on-street parking maintained on most streets in this period.

Extended Constraint Period?

The period from 2021 to 2024 may still be a constrained and congested time. Northgate Link is expected to provide relief when it opens in 2021, because more people will arrive by Link rather than in buses competing for limited bus lane space Downtown. Still, many commuter buses from the northern suburbs will continue Downtown rather than truncate at Northgate Station judging by early planning. It won’t be until Lynnwood Link and Federal Way Link opens in 2024 that the number of commuter buses Downtown will drop in a significant way.

Designing a Good Decongestion Pricing System

We don’t know much about what the City has in mind for a decongestion pricing system, but here a few suggestions to avoid likely pitfalls.

- Progressive pricing – Like ORCA LIFT, we should set up congestion pricing with significantly reduced rates for low-income motorists. That way this policy does not fall hardest on those who can least afford to pay.

- Dynamic pricing – Prices at peak commute hours should be high to discourage trips at this time, and significantly lower at less busy times to encourage trips to switch to off-peak. Maybe the Mercer Mess doesn’t have to be a mess if we balance trip demand.

- Consider lower rates for public-interest work trips – Some jobs, like social work or case managing, can require travel all over the city and all those trips would add up. We should consider a favorable rate for work trips for public interest jobs. We don’t want to decrease the capacity of social aid organizations.

- Use traffic cameras to ramp up enforcement of blocking intersections – Congestion is exacerbated by motorists who block intersections in their haste to make it through a traffic light. Congestion pricing will likely mean adding traffic cameras. We should use traffic cameras to tackle congestion caused from intersection blockage and to defend transit lanes from encroachment.

- Wisely spend the proceeds on transit – Congestion pricing will likely bring major revenue, so we should make sure we use for maximum benefit. High-impact transit investments could lessen the sting of tolls.

- A strong political campaign – Passing decongestion pricing is a big political lift and will require a strong political coalition with a smart campaign to pass the finish line. New York City has been trying to enact congestion pricing in Manhattan for more than a decade but continues to be thwarted. If it’s true that we’d need a public vote to do decongestion pricing as The Seattle Times reported, congestion pricing will have a tight-rope to walk. We will need a clear convincing message why decongestion pricing will improve transportation and livability in Seattle. Mayor Durkan will need to be a champion.

The Road Ahead

Mayor Durkan said she is hoping to enact decongestion pricing by the end of her first term in 2021. To do so would be a big win for urbanism and reducing traffic congestion and greenhouse emissions. When it comes to getting the basic protected bike network implemented, though, congestion pricing will likely come too late to change SDOT’s mind about key protected bike lanes like Fourth Avenue and Pine Street. Many North American cities from Calgary to Chicago to New York City have rapidly rolled out their basic bike networks downtown while Seattle has vacillated–apparently worried bicyclists would displace motorists who would then delay buses.

“Mayor Durkan is committed to reducing single occupancy vehicles downtown,” the Mayor’s press release states. “According to the 2017 Center City Modesplit Survey, transit use has skyrocketed by 41,500 in the last seven years in downtown Seattle during the peak morning rush hour. Walking, biking, and rideshare, including carpool, saw gains of thousands of trips per day. Conversely, the percent of commuters driving alone has fallen down to 66,500 single occupancy vehicles–the lowest rate since this survey began tracking trends in 2010 and a reduction of nine percent over the last year. The survey illustrates an overall decrease of approximately 4,500 single-occupancy vehicles in the city, despite employment growth of approximately 60,000 jobs since 2010.”

Decongestion pricing addresses the biggest source of congestion: single occupant automobiles. Reduce the quantity of cars and bikes and buses can efficiently mix and streets can become safer and more pleasant places to be. Congestion pricing can deliver this benefit, but, alas, it looks like we’ll see more foot-dragging on protected bike lanes in the time being. Instead, we’ll have deus ex machina remedies heavy on app-based “innovation” to distract us until this period of maximum constraint hopefully subsides.

Author’s Note: This article has been updated to use the term “decongestion pricing” rather than congestion pricing, since reducing congestion is the goal of the proposal. Jarrett Walker made the case for using the term “decongestion” pricing in this article.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.