I used to save these. They’re the bottom ends of transfer slips, leftover in the cutter after tearing them off for customers. I call them “transfer evidence,” and they’re exciting to me for what they represent.

There’s a sentimental streak in me that overvalues certain objects. We’re always leaving people, or they’re leaving us, and when we have the chance to say goodbye, we take it; transition looks too much like loss otherwise. We do what we can against the constant tide of reality becoming memory.

This is where artifacts find their greatest value. They expand in their meaning, become more than themselves: the plain white saucer on my kitchen counter, Jewish, from World War II. The typewriter with the fading ink band; the patches on your jacket, darned by a family member, decades past on a cloudy Tuesday. The objects that didn’t used to matter; how many memories do they now contain?

I particularly like transfer evidence because of how much it reveals, collectively. Each torn sheet represents a story, someone’s day, plans they had. Each paper is a person with a mission, infinitely different.

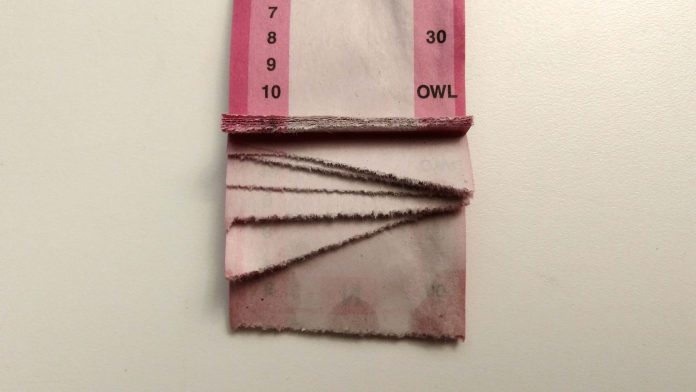

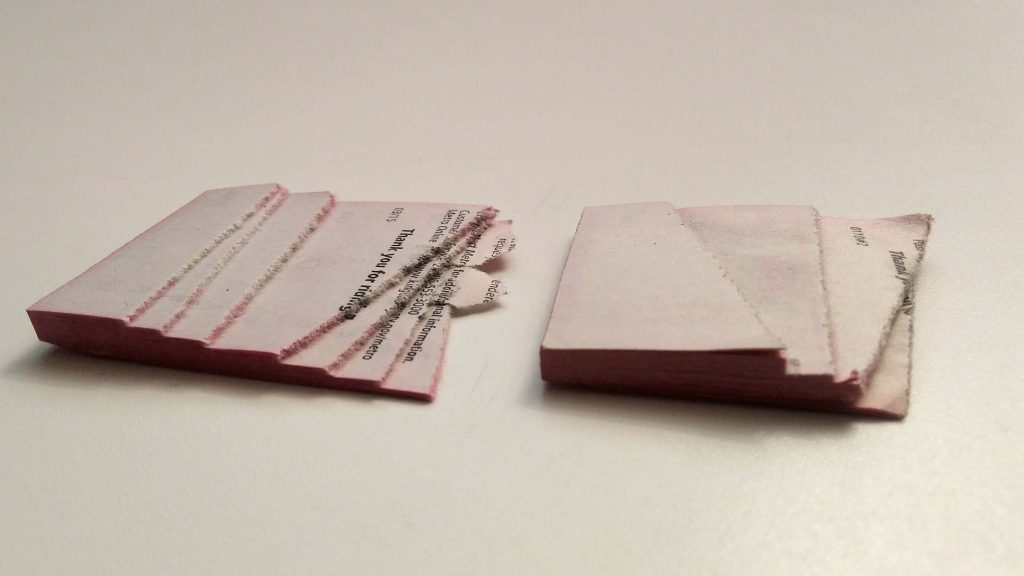

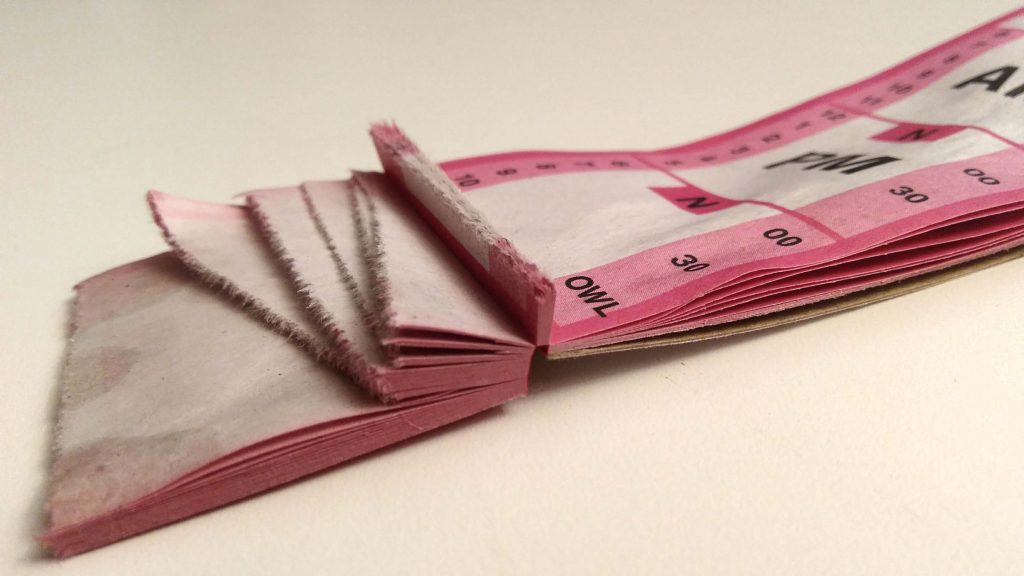

Each diagonal tear position indicates a specific trip, and more positions indicate more trips. Some trips are busier than others, and that gets reflected here too, in the varying thicknesses of each diagonal:

The day represented by the left batch in the picture above had more trips, but less people per trip, whereas the chunk on the right looks like just 4 trips, with the last 3 being very busy.

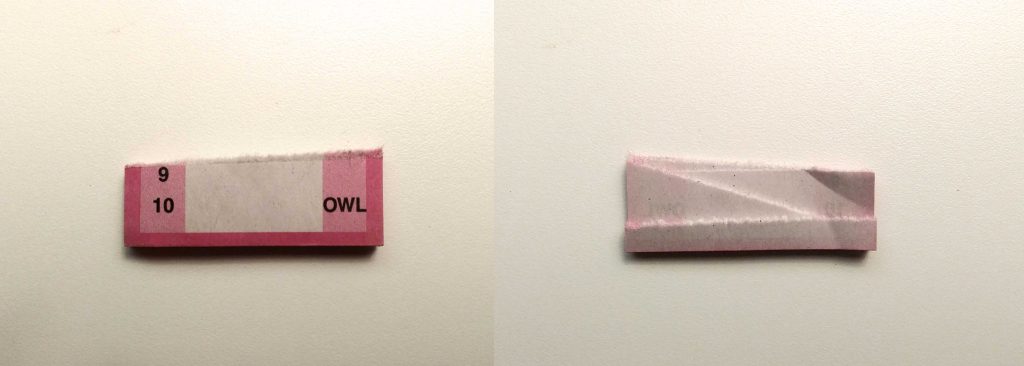

My night shifts involve longer transfers and thus shorter evidence. The thickest strip is at the very bottom, of Owl transfers torn that night:

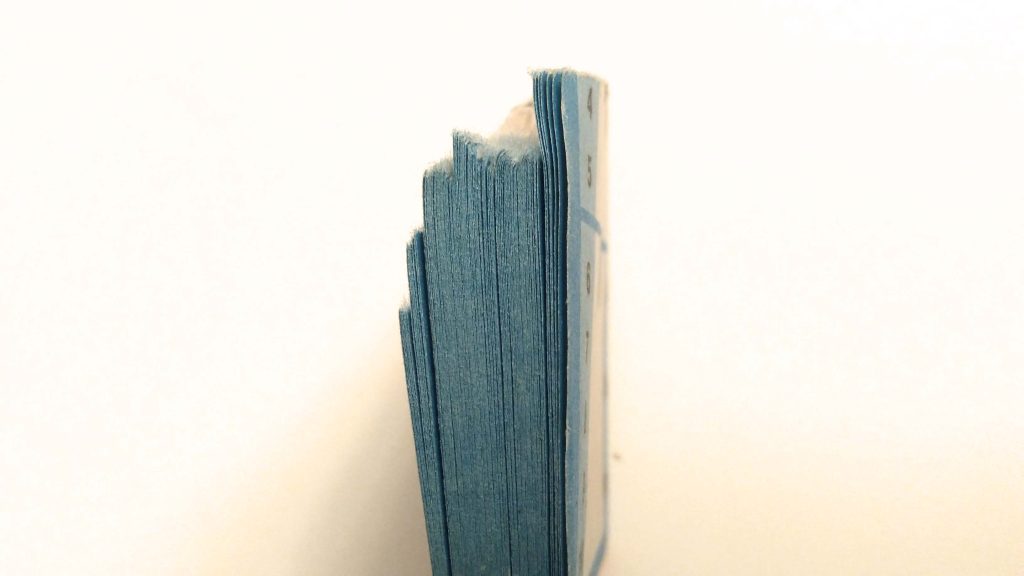

This is a busy day. When I drove the 358 I’d use an entire book of 100 transfers in three hours:

I no longer hang onto these like I used to, mainly for lack of space. As a hoarder I’m an utter failure, because I vastly prefer spacious and empty living areas. I can’t keep everything!

But sometimes I’ll still pause after the end of a long day, reflecting on that bushel of paper before tossing it in the blue bin, considering all they represent. Flipping through those little sheets. The jostled stress, the happy eyes, the students and mothers and lovers and sons, crowded together for only this hour, and probably never again. That was a lot of life out there that I just saw, I’ll think to myself.

Isn’t that kind of glorious?

Nathan Vass is an artist, filmmaker, photographer, and author by day, and a Metro bus driver by night, where his community-building work has been showcased on TED, NPR, The Seattle Times, KING 5 and landed him a spot on Seattle Magazine’s 2018 list of the 35 Most Influential People in Seattle. He has shown in over forty photography shows is also the director of nine films, six of which have shown at festivals, and one of which premiered at Henry Art Gallery. His book, The Lines That Make Us, is a Seattle bestseller and 2019 WA State Book Awards finalist.