Just a few years ago, the Seattle Mayor’s Office, eying a confluence of construction events getting scheduled downtown and an uncertain timeline for buses to exit the downtown transit tunnel, pulled back on needed safety projects downtown for people on bikes. In classic Murray administration fashion, a taskforce was convened, taking the political pressure off the 7th floor of city hall and onto an “advisory board” and the four agencies–the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT), King County Metro Transit, Sound Transit, and the Downtown Seattle Association–that they would work through issues with. One Center City, we were told, would find the solution.

Last fall, we reported that, after many months where it felt like the only conclusion the group would arrive at would be the status quo, a framework for weathering the “period of maximum constraint” had been found, and it actually seemed to present a unique opportunity to move the most number of people through downtown during a tricky time.

After the recommendations, Seattle’s political landscape got a bit upended, we went through three mayors in as many months, and One Center City’s recommendations sat on a shelf, waiting for those in charge to pull the trigger. As the clock ticks toward the closure of Convention Place Station, the demolition of the viaduct, and construction for the Center City Connector, Mayor Jenny Durkan hasn’t made any announcement about what will be done on Seattle’s streets when buses exit the tunnel next year, though she did allude to it in her State of the City address last month:

It’s no secret that our traffic is bad and our buses are full. The bad news is traffic will get worse before it gets better. Mega projects will lead to mega gridlock. The good news is, more people are using transit, and fewer people are driving alone in their cars. We need to keep that trend going.

Though traffic will get more challenging, I pledge to you that we will continue to get more creative, we will make necessary investments, and we will improve these numbers. To find ways to bust through gridlock, and make it safe for pedestrians and cyclists. Along with delivering basic services, we will deliver the most essential service of all: A safe and just community.

Now rumors are circulating that, like her predecessor, the mayor may decide that adding new bike lanes downtown are not politically palatable. To be honest, this is an easy choice to make. But pulling out the bike components is short-sighted, and it only takes a quick look at the information that the One Center City advisory board used to make their decision to understand why.

It’s About Moving People

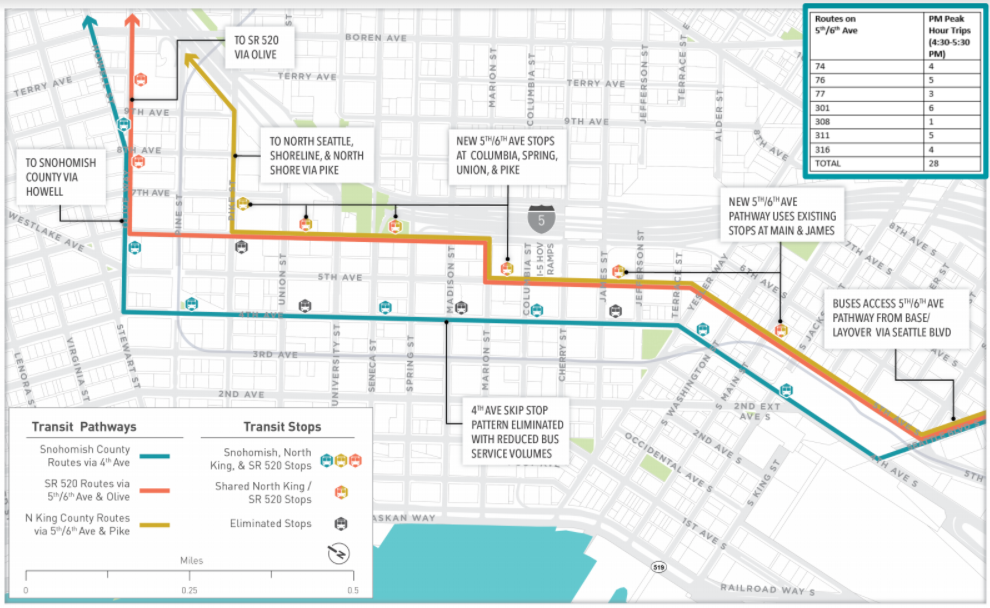

The pinch point once buses exit the tunnel is 4th Avenue, at least until Northgate Link opens. The current bus lane on 4th Avenue can’t handle as many northbound buses as would need to use it, in part because that lane also handles right-turning vehicle traffic off of 4th Avenue. There also isn’t enough curb space for all of those buses to stop during peak hours. So some buses would use an alternate pathway via an extended contraflow bus lane on 5th Avenue north to Marion Street, where they’d switch to 6th Avenue.

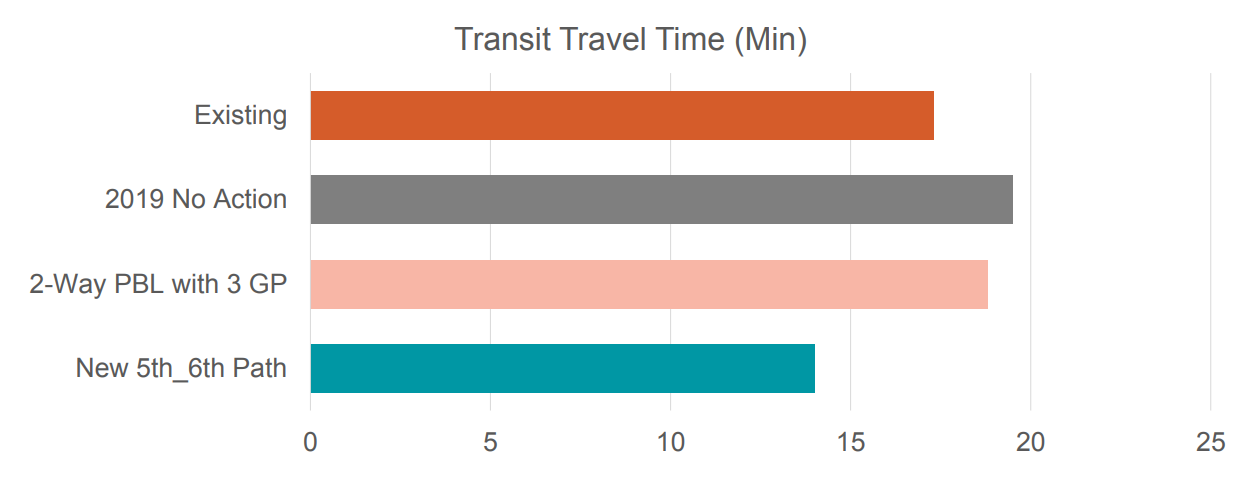

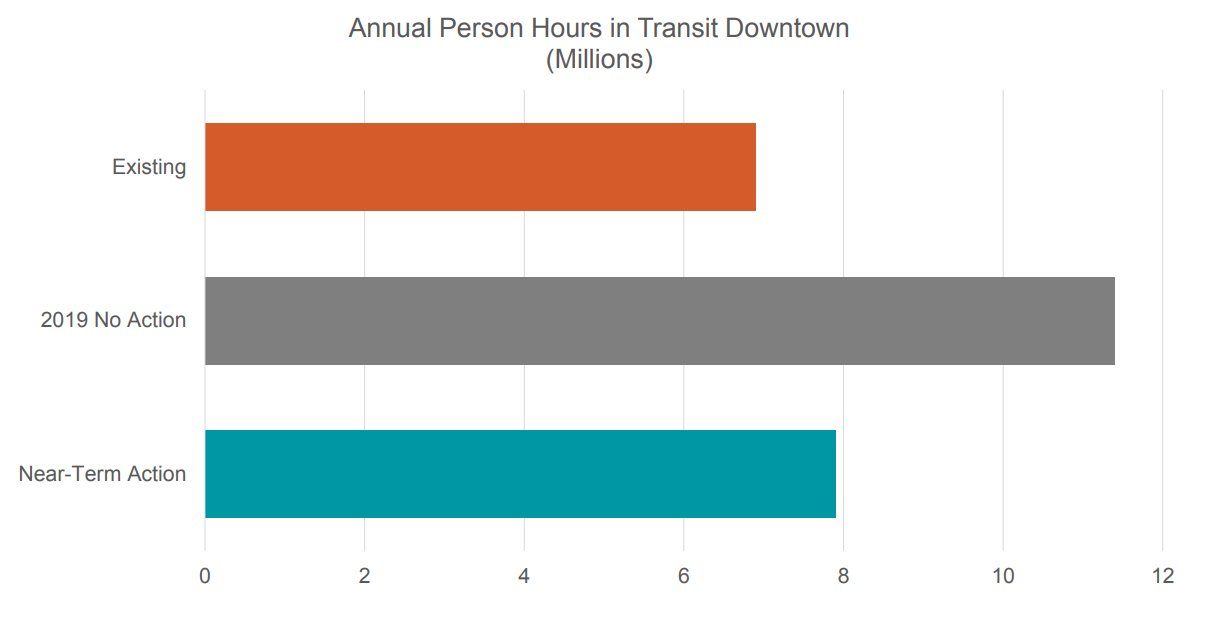

Overall transit time would be dramatically reduced with the 5th/6th Avenue transit pathway:

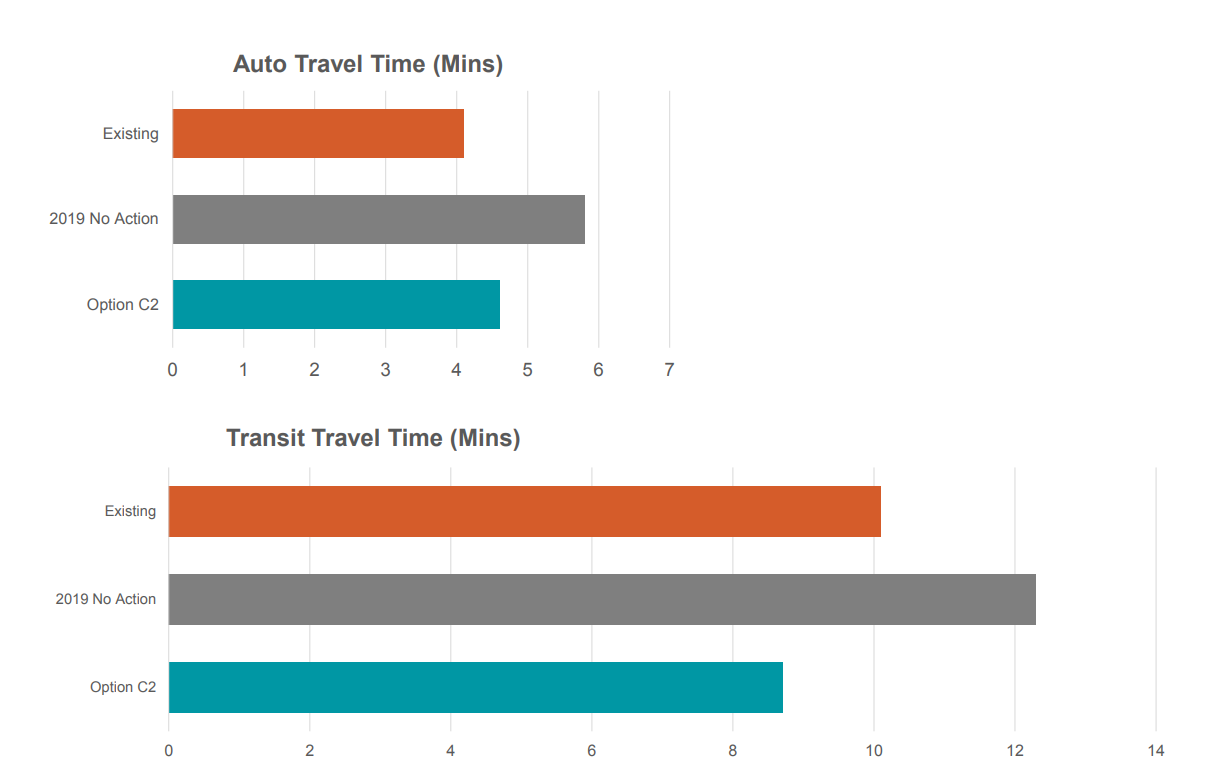

Where will the additional buses coming to 4th Avenue go after they are ejected from the tunnel? In places where right-turning traffic uses the bus lane, SDOT will install upgraded signals that separate pedestrians from turning traffic, making pedestrians safer while getting traffic out of the turning lane so buses can go forward. This would both dramatically improve travel time for buses and improve travel times for general purpose traffic compared to doing nothing.

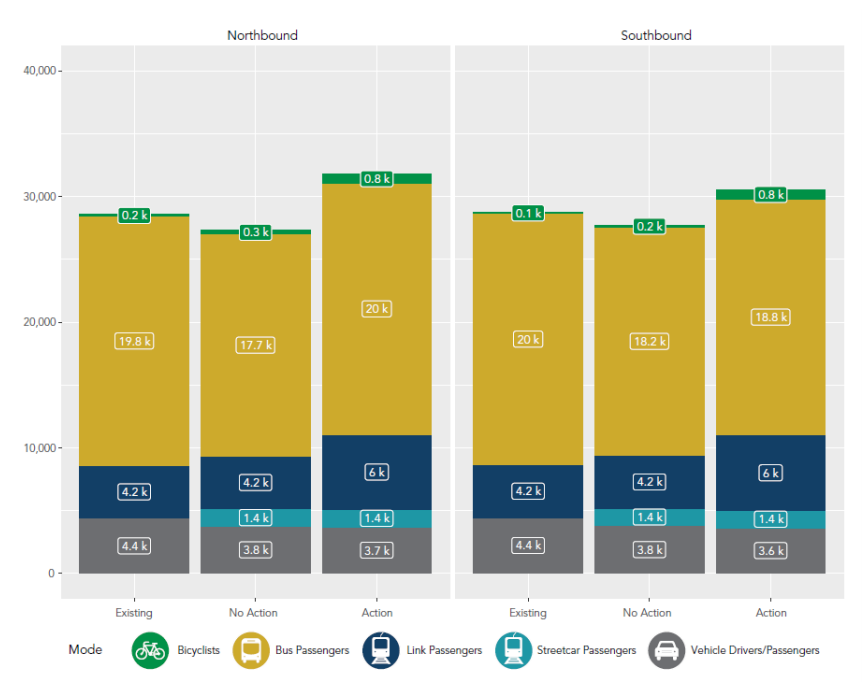

What impact will this have on the amount of people we can move through downtown? A dramatic one. With Link able to handle even more passengers with buses out of the tunnel, northbound buses and Link will be able to move 26,000 people per hour northbound, 2,000 more than the current baseline, not even including the number of people who will be moved on a new streetcar line. So much for the period of “maximum constraint”. More like the period of maximum opportunity, if we don’t let it slip by.

And the cost of doing nothing? It is estimated at over a million and a half annual person hours spent on transit. Even at the minimum wage of $15 per hour, that’s $22.5 million dollars in lost productivity. We could pay for a year’s operation of the streetcar network with that money (I think).

It’s About Safety

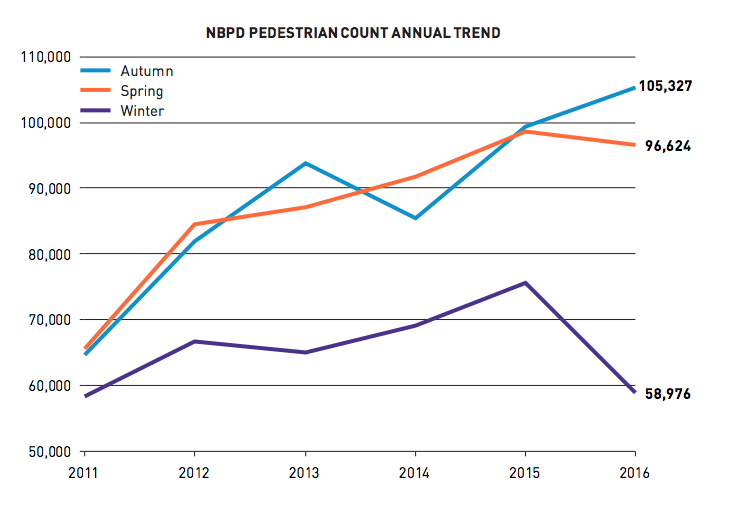

OK, what does this have to do with a bike lane on 4th Avenue, you may be asking yourself. Why cram that in there when we’re trying to move transit? The answer is safety. Remember those turn phases I mentioned at right turns on 4th Avenue? To reduce conflicts from left turning vehicles (on the one-way street) we also need them on the west side of the street. Pedestrian volumes downtown are skyrocketing. Conflicts between turning vehicles are one of the most common types of collisions.

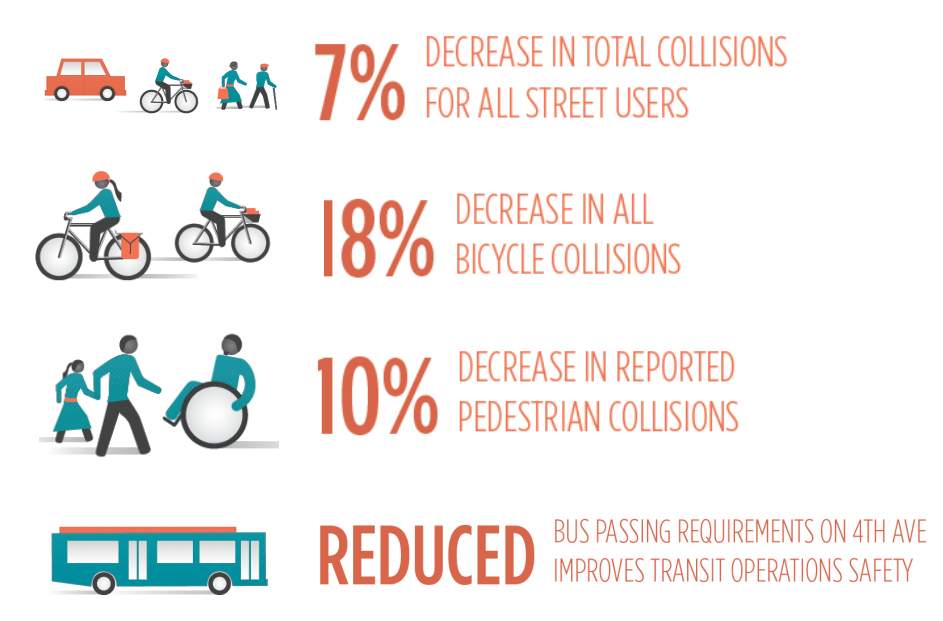

Preventing traffic from freely and unsafely turning across high-traffic crosswalks are one of the things that would slow down people driving on 4th Avenue, but here the costs clearly do not outweigh the benefits. And because left turn signals are also needed to accompany the installation of a protected bike lane along the west side of 4th Avenue, the choice is not between moving buses, or cars, and adding a bike lane, but rather between retaining parking and adding a bike lane.

While the entire length of the proposed bike lane is not parking, much of the proposed bike lane would take the place of a parking lane. And so we have to ask ourselves: during the period of maximum constraint, do we want to use the street to move people, or do we want to use it store cars? Particularly when downtown’s off-street parking garages are rarely full, and the city has spent quite a bit of money on a program to inform drivers where they can find off street parking?

And do we want to keep people safe, both on foot and on bikes? The most compelling numbers presented to the board were these: a projected 7% decrease in total collisions, including an almost 20% decrease in projected bicycle collisions and a drop in pedestrian collisions by 10%.

We will not see these improvements if we don’t move forward with a comprehensive approach to remaking 4th Avenue, and its counterpart, the 5th & 6th Avenue transit pathway, as soon as possible. Pulling out segments of the plan that was arrived at with the help of out most important regional agencies because they are politically unpalatable sounds like the work of a previous occupant of city hall. It’s time to put safety–and moving people–first.

You can contact your lawmakers here to let them know that expanding the center city bike network is an integral part of moving forward with a multimodal downtown, courtesy of Seattle Neighborhood Greenways.

Featured image: Scott Bonjukian

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.