The Cascadia high-speed rail cost estimate in the preliminary study caused fiscal conservatives to clinch their cheeks together. Nonetheless, plenty of reasons exist to move forward with further study at the very least. The fiscal hawks tend to fail to mention the economic analysis appended to the same study: it found building high-speed rail adds more than a quarter trillion dollars of public value in two decades. We also too often forgot how common high-speed rail is in Asia and Europe, and in similar corridors to Cascadia. Portland to Vancouver is a ripe corridor for high-speed rail (HSR).

Uniting Cascadia: The Benefits of Agglomeration

In addition to estimating 200,000 jobs created during construction, the preliminary study touted the economic benefits of agglomeration–a fancy term for people and firms clustering together–which allows economies of scale and network effects that increase productivity.

“The large reduction in travel times associated with implementation of HSR will foster greater accessibility for workers and employers,” the economic study authors wrote. “Business productivity benefits from employers’ access to a broader and more diverse labor market with a better fit of workers, skills, and access to a wider customer market. The increase in effective economic density (or clustering) of economic activities supported by the HSR’s operation and stations will enhance the productivity of the economy through firms’ or workers’ ability to access a wider range of offices, retail, entertainment centers, and other land uses within the same travel time.”

Urban agglomeration was a major theme underlying Jane Jacobs’ writing figuring prominently into several of her works such as The Economies of Cities. High-speed rail brings Cascadia’s three main economic hubs–Vancouver, Seattle and Portland–a lot closer together, while also tying together in-between cities like Surrey, Bellingham, Everett, Tacoma, Olympia, and Kelso/Longview. The study sought to measure the expected agglomeration effects to get a fuller picture of the total economic benefits.

“The total impacts over the 10‐year construction and 21‐year operating periods include:

- 157,200 to 201,200 average jobs per year

- $242 billion to $316 billion in labor income

- $621 billion to $827 billion in business output

- $308 billion to $399 billion in value added.”

Value added, or GDP, increases by $264 billion to $355 billion over the 21-year operating period over a “do nothing” alternative, the study found. Value added includes profits, taxes, subsidies, wages, income, and benefits. Thus, the modeling suggests the investment would add value tenfold or more in two decades compared to its estimated one-time capital costs. Moreover, business would also gain more than half a trillion in additional output over the same period. Economic returns on that magnitude would dwarf the considerable capital costs estimated between $24 billion and $42 billion in the preliminary study–even after applying a reasonable discounting rate to factor in inflation and opportunity cost.

“The concentration of economic activity and mobility to access various parts of the corridor provided by the HSR service provides an opportunity for more face‐to‐face contact and for access to specialized labor, which result in higher productivity and more economic growth,” the authors wrote. “The reliability and mobility of the service improves the overall quality of life, and the attraction of both businesses and employees to the region supports additional growth and development, resulting in agglomeration economies.”

A Dense Megaregion

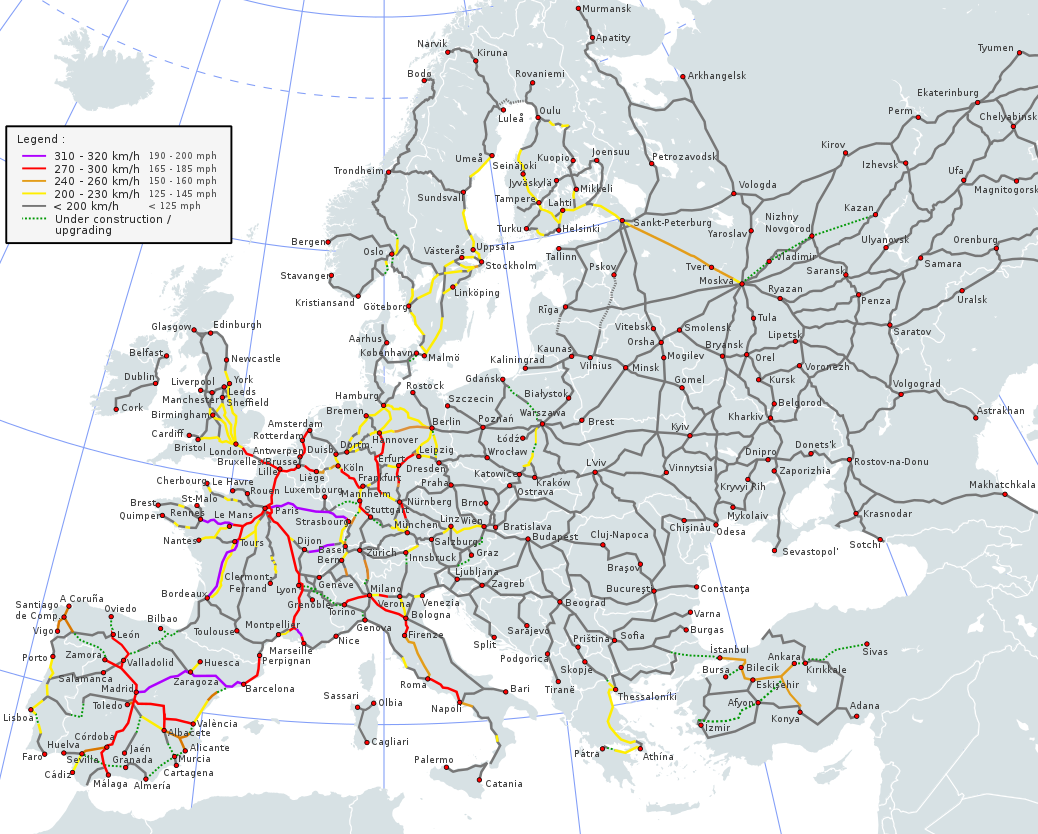

Some have suggested Cascadia just isn’t dense enough to support high-speed rail. However, the Cascadia’s projected 2040 population of 13 million can compare with many similar high-speed rail corridors in Europe.

Italy–hardly a paragon of efficient or corruption-free governance–is lapping the US on high-speed rail. Rome and Naples are connected by 70-minute express high-speed rail and are about the same distance apart as Vancouver and Seattle and with comparable metropolitan populations. In Northern Italy, high-speed rail connects Milan to Turin and to Florence (via Bologna). Milan is larger than Seattle at about 8 million residents in the combined statistical area compared to Seattle’s 4.7 million. However, Turin, Florence, and Bologna are all smaller than Vancouver or Portland. As a result, the 461-kilometer (286-mile) Florence to Turin HSR corridor accounts for about 13 million people, which is also the projected 2040 population of the 508 kilometer (315-mile) Cascadia corridor.

France’s high-speed rail network includes corridors similar to the Cascadia corridor. Obviously having a city as dynamic and massive as Paris at the hub is a unique advantage. That said, the express train from Paris to Bordeaux covers 367 miles (590 km) serving a corridor population similar to Cascadia with 24 trips per day.

Turkey has high-speed rail between megacity Istanbul (15 million) and the Turkish capital Ankara (5.5 million) but also between Ankara and Konya (2.1 million), bringing the 193-mile (310 km) trip to two hours with two in-between stops. It wasn’t long ago that some Westerners derided Turkey as a third-world country, but on high-speed rail anyway Turkey is the developed country with the United States the underdeveloped one.

Advantages Over Air Travel

The other major criticism of high-speed rail is it can’t compete with air travel; however, to someone living in or near Downtown Seattle hopping a ultra high-speed train to Portland or Vancouver is much faster than flying. Airports instruct travelers to arrive at least one hour early. In Seattle, the light rail trip to Sea-Tac alone takes about 45 minutes and drops off passengers a 10-minute walk from security. High-speed rail passengers might already be at their destination while air passengers are still standing in line at security.

Air passengers repeat the same routine at their destination, traversing long distances from gate to exit at the airport to catch a train or taxi to downtown Portland or Vancouver–which may add another 30 minutes or more. Due to all the rigamarole, downtown to downtown travel times between the major Cascadian cities might be closer to three hours rather than the one hour high-speed rail offers (or two hours from Portland to Vancouver). Rail’s ability to drop off travelers downtown is a huge advantage. Rail’s efficiency in boarding and deboarding and lower cost allows high-speed rail to be competitive with air travel on trips up to 600 miles (965 km) according to the Federal Railroad Administration.

High-speed trains are also electric whereas air travel’s high-octane fuels comes with a high environmental impact. Electric air travel is still speculative at this point. One Kirkland-based company is promising to deliver to small hybrid electric planes to market in 2022, but they’d only have a top speed of 340 miles per hour and seat 12 at most. Full-size electric commercial planes seem a lot longer off. Airports are expensive pieces of infrastructure to maintain in their own right with the Port of Seattle planning multi-billion dollar terminal expansions to keep up with demand. High-speed rail decreases strain on busy airports, perhaps saving them some expensive capacity upgrades down the road.

High-speed rail would meet the promise of a region that bills itself as cutting edge while its regional transportation is decidedly behind global peers. The preliminary study of economic impact suggests urban agglomeration effects would more than pay for high-speed rail’s sizable upfront price tag. And the preliminary feasibility study already showed that high-speed rail would attract enough ridership to support its operational costs. We should follow through with the full business case study, as Governor Jay Inslee has proposed, so that we do not let this opportunity slip between our fingers. It appears $1.5 million of the requested $3.6 million has been lined up after the Washington State Legislature authorized $1.2 million and British Columbia provided $300,000 more.

The economic impact study starts at page 77 of WSDOT’s report:

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.