From its inception, Northgate Mall has been a beachhead of autocentric suburbia within Seattle’s urban landscape. So it came as a surprise and joy to many urbanists when the Seattle Times, Puget Sound Business Journal and other outlets wrote last week that Simon Property Group plans a major redevelopment of Northgate Mall with the addition of office, housing and open space to what is now just parking and retail. The long overdue redevelopment makes sense with light rail service coming to the aging mall’s front door in 2021. It also contains many of the ideas expressed by Charles Bond in a 2014 article in The Urbanist titled 10 Ways Northgate Mall Could Become ‘Downtown Northgate’. I’m not saying he is the inspiration for all of this, but he did a great job identifying many of the issues.

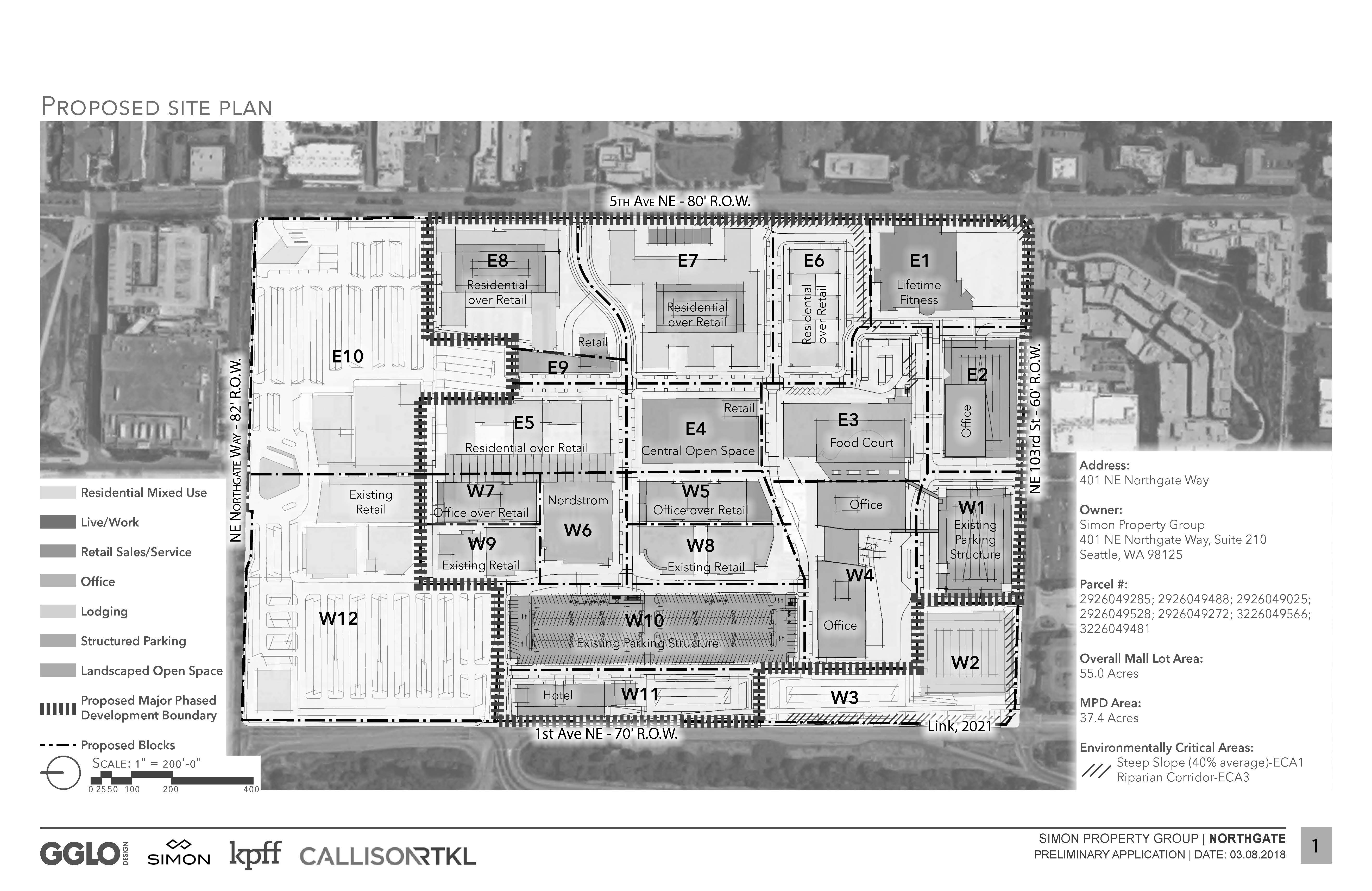

The preliminary report says they envision having about 500,000 to 750,000 square feet of retail, 500,000 to 750,000 of office, several hundred units of housing and a hotel. Their site plan also shows a new square at the heart of the project. But is that enough? Is a city just a mix of places to work, shop and sleep or are there other qualities we as urbanists need to advocate for as this project moves forward? And is it enough housing to make a neighborhood or should we be advocating for more?

How Much Housing is Enough?

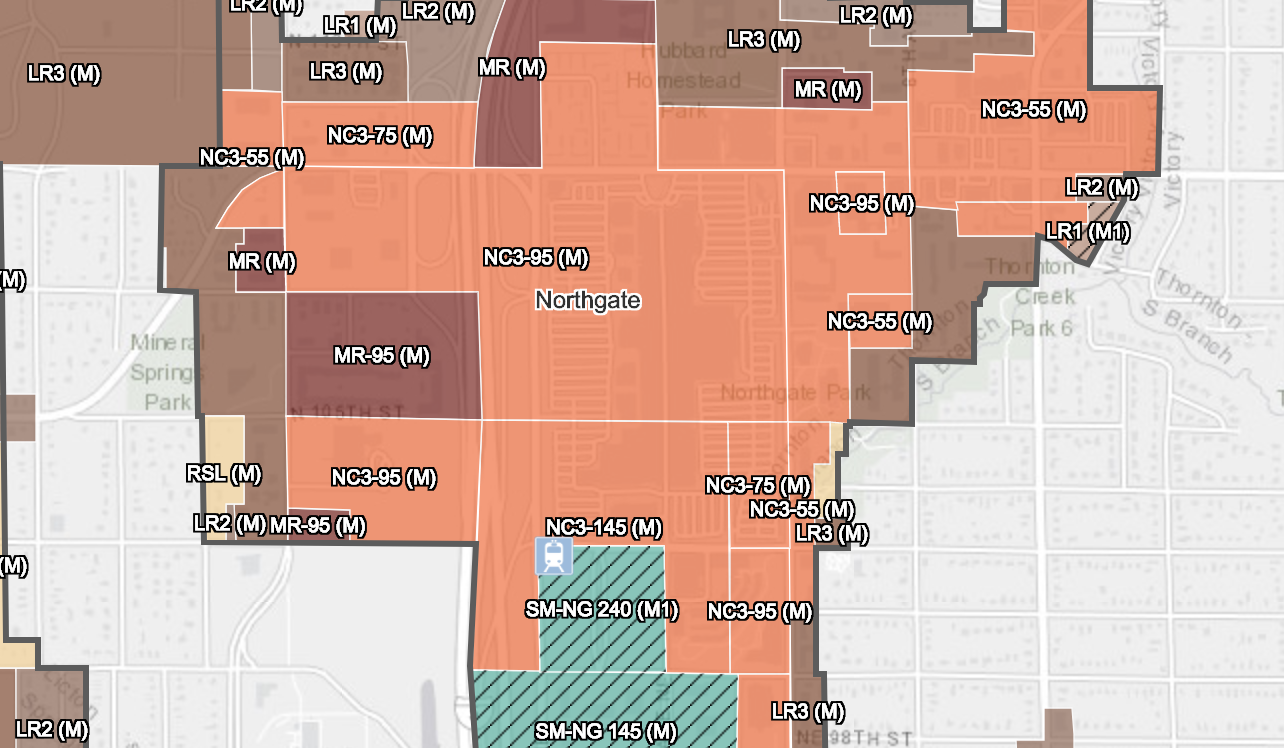

The early press for this project has said that the developer expect to include several hundred units of housing in this project, but is that enough to change a neighborhood? Is that enough in the midst of a housing crisis? Directly adjacent to a light rain station? I don’t think so. Part of the problem is that the city has chosen a relatively timid option for upzones in the area as part of the MHA process. Most of the site is currently zoned with a 85-foot or 125-foot height limit. Under the MHA preferred alternative they will be raised to 95 feet and 145 feet respectively. As I said above, this area is directly adjacent to a Link station, has no residents to displace and no historic buildings. It is parking and shopping center, the ultimate pain free target for redevelopment. The city should raise the height limit much higher than it is—even to 240 feet as it is directly south. Failing this, the developer should ask to be upzoned. This would mean more housing neat transit and more affordable units, expanding upon the large mixed-income complex planned on publicly owned land next to the station.

A similar redevelopment of surface parking and and aging theater at Lloyd Center mall in Portland plans to add about 1,200 units in two phases and this is coming shortly after a separate developer built about 600 units (and the largest bike garage in North America). Interestingly, one of the architects told me that the idea with the 600 units that have been build at Lloyd Center was to build enough housing simultaneously that it would catalyze a change in perception of the neighborhood over night. Just having that many new residents would lead to a rethink of what that part of the city is about. This is exactly the kind of thinking that Northgate needs now.

Urbanism is Not just Buildings and Density

Possibly the largest danger in redeveloping this key site is that it doesn’t get woven back into the city’s grid, but rather it becomes an insular island of walkable urbanism that continues to exist within a very suburban context. One has no farther to look than University Village to see this tragedy unfold. What was once a typical mall had densified and become more walkable, but also has chosen to turn its back to the rest of the city by walling itself in with parking garages and streets that are hostile to walking and biking. Within the development it is wonderful for strolling and shopping, but the expectation is that its visitors will all arrive by car and very little effort has been made to reconnect it to the surrounding street grid.

In the case of Northgate they are proposing to redevelop 37.4 acres (though the entire property is 55 acres). The surrounding blocks are roughly 3.7 acres each (600 feet by 270 feet) so the grid could be reestablished and the proposal could be broken into 10 normal sized blocks. As it is it looks as though they are making an effort to divide up the site and possibly reestablish the grid where possible–though several of what look like streets appear to be terminating in parking lots. This is an issue we should watch as the project moved forward. We should also work to insure that what streets are built are public and complete.

There is another precedent for failed urbanism across the lake that shows how Northgate could go awry: Bellevue. From the Seattle side of the lake it appears to be a city, but when I have ridden my bike through I find it to be a suburb with high rises. By this I mean it has allowed density, but chosen to privilege the car over walking, biking and transit. With its super block, wide streets and massive parking garages it has failed to cultivate any street life. This also mean that the level of auto dependence remains high, negating much of the climate change benefits of density. This is where the city can and should step in and use this as an opportunity to tame some of the streets that run through the area. By slowing traffic and reorienting roads for walking, biking and transit the city could avoid the pitfalls of Bellevue and enhance the areas potential as a residential neighborhood where people can safely access the new Link station.

No Risk, No Reward

No matter what happens with the redevelopment of Northgate Mall, it will surely be better than what is there today. The owners should be commended for taking this step. That being said, this is a once in generations opportunity to shape a whole neighborhood in the heart of the city, and the tone set with this project will have repercussions for decades to come. So we should strive to make this the best version of the project it can be and advocate for the most housing and the most walkable, bikeable and transit-friendly streets and sidewalks we can. If we succeed, we can lay the groundwork for Seattle’s next great neighborhood. If we fail, we will have to wait decades for another opportunity to have such a radically positive effect on this part of the city.

Patrick grew up across the Puget Sound from Seattle and used to skip school to come hang out in the city. He is an designer at a small architecture firm with a strong focus on urban infill housing. He is passionate about design, housing affordability, biking, and what makes cities so magical. He works to advocate for abundant and diverse housing options and for a city that is a joy for people on bikes and foot. He and his family live in the Othello neighborhood.