It looks like the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) is about to apply the brakes to Seattle Department of Transportation’s car funnel that is the new Mercer Street. A few weeks ago the state transportation agency installed signals that will allow it the ability to meter the five lanes entering I-5 from Mercer, both northbound and southbound. This Saturday, those meters will get turned on, but only on weekends; weekday metering will not start until after April 10th.

For almost a year now, the upgraded Mercer Street traffic signal technology from Uptown to I-5 has been doing what it was intended to: increase vehicle throughput. Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) picked the corridor to be the first in the city to get the “adaptive signal” treatment after the complete rebuild of the street from one-way to two-way, completed in 2014, resulted in travel times that were around the same as they were pre-construction due to the much higher volume of cars on the new two-way Mercer. Called SCOOT, the system’s objective is clear, if not linguistically, on the SDOT project page: “to keep people driving moving”.

Because the signals along Mercer keep traffic moving by prioritizing east-west movement for cars, other types of travel are not prioritized. Last summer, Mark Ostrow outlined how pedestrians were being impacted: walking time frequently lags behind the time allocated for traffic in the same direction, leaving many pedestrians waiting at the curb. Because the adaptive signal system measures vehicle throughput and not pedestrian (or bus rider) throughput, it can’t prioritize the latter, except in heavy-handed ways around the margins of the system. In November, SDOT tweaked the amount of time pedestrians were allocated to cross Mercer in one cycle, which also resulted in fewer walk cycles overall. After all, as SDOT’s blog post on the issue mentioned, “As for walk cycles, it’s important to note that…Mercer[‘s eastern portion] has high vehicle volumes.”

With the average daily traffic levels on Mercer at Fairview going from 37,900 vehicles in 2010 to a staggering 66,100 in 2016 (the most recent year for which there’s data available), it’s not surprising that Mercer’s ramps might be dumping more traffic onto I-5 than can safely merge onto the existing lanes. But it begs the question as to how sustainable SDOT’s approach of prioritizing east-west traffic to and from the freeway is long-term. We don’t yet know exactly what the impact to the capacity of Mercer Street will be with these new ramp meters, but it’s beginning to look like the multi-million dollar investment in smart signal technology simply moved the bottleneck onto I-5.

In addition, SDOT has stated the goal of expanding SCOOT technology to another chronically congested corridor nearby: Denny Way. Denny is also congested with vehicles getting to and from I-5: how will adaptive signal technology work with ramp metering? Will the car funnel only work until WSDOT needs to implement freeway demand management on the on-ramps there? Will this issue come up with nearly every corridor that leads to and from I-5?

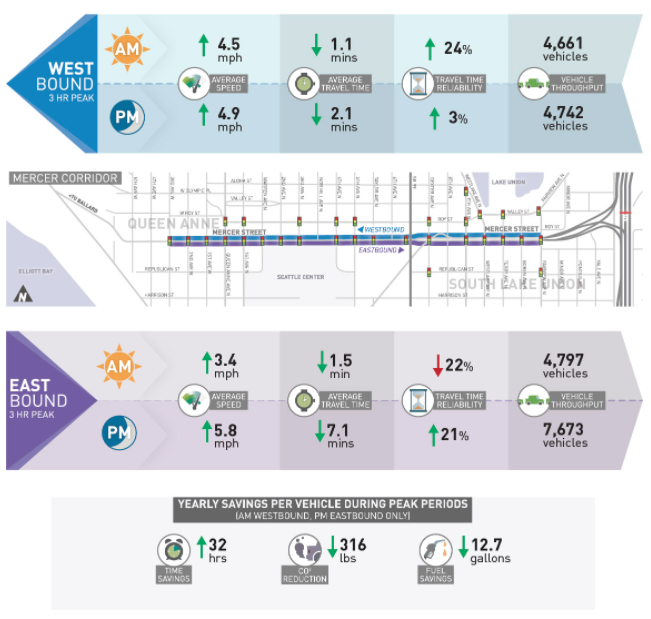

Since the launch of SCOOT on Mercer, regular statistics have been posted to the project page showing the system’s performance. The data from January of this year shows 7,673 vehicles moving through Mercer during the three hours of PM peak, when there is the most eastbound demand on the street. That’s actually down from the first few weeks of SCOOT’s implementation, where the total numbers were closer to 9,000 vehicles.

The most remarkable part of the results of Mercer’s signal upgrade as presented by SDOT is the assertion that carbon emissions are being reduced as a result. According to their numbers, from January, the average vehicle is emitting 316 fewer pounds of carbon per year as a result of the efficiencies gained though these signals. To assert emission savings from a street that has seen overall vehicle numbers grow by almost 30,000 per day in just six years is, well, dishonest. In a imaginary world where the number of cars on a street remains exactly the same all the time, yes: moving cars more efficiently will reduce in less idling and fuel and carbon savings. But as traffic improves, more people will be persuaded that they’d like to drive on Mercer. Improving the “efficiency” of the street has the same induced demand result as adding another lane, just on a slightly smaller scale. On the flip side, we see a de-prioritization of other less carbon-intensive modes, which has the same effect of inducing driving.

As cities around the country become aware that expanding their major streets is a fool’s errand, they increasingly appear to be turning to multi-million dollar signal investments as an alternative to adding lanes. But “intelligent” signal technologies may be the urban freeway expansions of the 21st century: demand inducers that turn cities away from the real cures of urban congestion: safe places to walk and bike, dedicated transit, and demand pricing.

Tomorrow, the City Council’s Transportation and Sustainability Committee will be considering whether to authorize a federal matching grant to implement intelligent traffic systems around the University of Washington. At this point, it’s not exactly clear what a $4 million grant from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) would go toward, just that it’s earmarked for “advanced transportation and congestion management technologies”. The matching grant would be coupled with $5.5 million in city funds. If streets in the University District are being readied for the same “upgrades” that Mercer Street received, we should ask ourselves if those improvements are in the long-term interest of our city and our planet, or if we’re just moving bottlenecks around again with the quixotic goal of improving congestion.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.