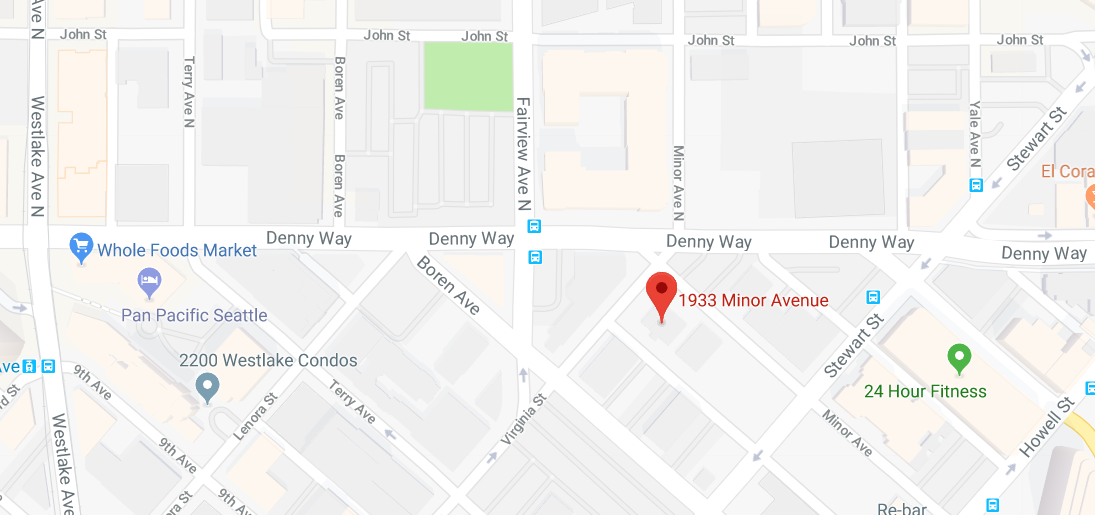

When Mayor Jenny Durkan announced her “Building a Bridge to Housing for All” plan to sell a prime city-owned parcel at 1933 Minor Ave in the heart of Denny Triangle for $11 million in order to fund some “bridge” housing and rental vouchers, some lamented the permanent loss of public land for temporary relief.

Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda was among the skeptics. At a Welcoming Wallingford meeting on Wednesday, Councilmember Mosqueda proposed a stricter policy in selling off public land, and even kicked around the idea of a moratorium on sales of city-owned land until such a policy is in place. She said that Mayor Durkan asked her to sign on to the plan. However, Councilmember Mosqueda said she declined because she was concerned about losing public land.

“The thing with funding for those who are unsheltered–we need that desperately as well–but it should go into capital projects so we’re actually building the housing,” Councilmember Mosqueda said. “One thing I can put out there is there a possibility of a moratorium on sales until we can get those conditionalities worked out.”

Seattle’s Communication Shop

The parcel in question here houses a communication shop–a one-story structure mainly for storing vehicles while they get worked on–for the city’s information technology (IT) department. 40-story towers are sprouting all around the site, close to Denny Way and some of the tallest height limits in Seattle. In the same megablock, Miami-based developer Crescent Heights plans twin 39-story towers at 1901 Minor Ave. If that project goes forward, tower spacing rules would likely shrink the buildable envelope of the communication shop site; one of the towers would be close to the lot line and require an 80-foot buffer above the tower podium (the first eight floors).

The city’s justification for selling the site is that developing affordable highrises is challenging and private developers already bought up the properties neighboring the small site, Councilmember Mosqueda said. Having a small site limits redevelopment potential and even if a large enough site was pieced together, it’s true the Seattle Office of Housing and its non-profit partners have mostly shied away from highrise projects. A 13-story project planned in First Hill would be the first affordable highrise built in Seattle in more than 50 years.

A good bet is the City will sell its site to Crescent Heights since the developer has a bigger proposal it’s been simultaneously working through the permitting process that includes the City site–not to mention an award-winning experimental design they’ve been kicking around. The full block proposal has 943 apartments and 662 underground parking spots, compared to the 737 apartments and 424 parking spots planned on the smaller lot. Like the smaller proposal, it cleared design review in 2016, but still needs a master use permit. Both proposals vested before the Seattle City Council passed the Downtown/South Lake Union rezone, meaning the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) requirements wouldn’t automatically apply to them.

Tackling Underused Public Land

Councilmember Mosqueda wants a comprehensive city policy dealing with underused public land and suggested a city-run land bank could be a way to more proactively acquire land before it’s snapped up by private developers.

“I’ve been saying where’s the full map of all of the publicly available land so we can build on that land right now,” Councilmember Mosqueda said. “The city has a map. The county has a map, but it doesn’t sound like we have a full map yet. It sounds like one is coming in March, but I’m like it’s 2018; I want to know how many parcels of developable land that we have available that are not just sitting empty–like a lot–but also underutilized.”

There’s an argument that an underused public land survey should include land locked up in urban freeways and their interchanges and frontages. Freeway lids can unlock land such as Lid I-5’s proposals to reclaim more than a dozen city blocks adjoining the University District which are currently a tangle of on- and off- ramps. There’s also several proposals for a Downtown I-5 lid–and I’ve also thrown out the idea of removing I-5 entirely from Downtown Seattle, either of which could put public land to much better use.

A public land usage policy may have avoided some blunders. I wrote about the issue of squandering public lands back in 2015. The Seattle City Council has managed to let a property right under its nose go to waste for a decade: the long-embattled Civic Square project, also known as the empty pit across from city hall. An updated 57-story design appears finally to be on the path to actually getting built; the planned 520 apartments will be market-rate with the city pocketing $5.7 million for its affordable housing trust fund and $16 million from the purchase price. That $21.7 million the city is ahead could quickly get sunk into land costs if it hopes to acquire another site in the downtown core to build. Of course with the threat of a lawsuit weighing down the city’s options, the Civic Square deal may have been the best that could be made of the situation.

Acquiring land is one of the biggest hurdles affordable housing providers must negotiate. Typically non-profit builders seek city subsides to finance their projects after they’ve secured a site, which is an increasingly competitive bidding process as the real estate boom continues and prime sites get rarer. Better leveraging land the public already owns offers a way out of this conundrum. In some cases, perhaps public land can be leased rather than sold to keep the valuable sites in public hands. Additionally, to exert more control and pick up the pace of affordable development, Seattle could take a direct role in building public housing rather than relying so heavily on non-profit developers. Councilmember Mosqueda indicated she’s open to the idea of Seattle Office of Housing directly building public housing again.

The communications shop site would have presented some big opportunities for public use. Perhaps a public library and community center (the first in either Cascade or South Lake Union) with several stories of mixed-income housing overhead? Even with a lot too hemmed in for a tower, worthwhile projects may have been possible.

Mayor Durkan’s Bridge Housing Plan

Meanwhile, Mayor Durkan’s press release focused on the perks funded by $11 million in proceeds from the sale: “This one-time investment would leverage $3.5 million for essential city services and $10.7 million for affordable housing, safer spaces for those without shelter, and provide housing stability for households on the verge of homelessness. The sale of the property located at 1933 Minor Avenue is expected to close in Summer 2018.”

- $5.5 million in a Bridge Housing Investment Strategy to increase our capacity for people experiencing homelessness in new bridge housing and shelter. “This strategy will kick off with a project to serve chronically homeless women in our community by the end of Spring 2018 with additional solutions to be deployed later this year;”

- $2 million for Seattle Rental Housing Assistance Pilot Program which is a rent voucher program Mayor Durkan outlined on the campaign trail last year.

- $2.5 million relocating Seattle IT’s communications shop and acquiring a new lease;

- $1 million for design costs for a new Seattle Fire Department facility; and,

- $2 million upfront Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) payment for building affordable housing. “The city

will be able to leverage the full payment of approximately $7.7 million several times over through other funding sources.”

In other words, $3.5 million (31%) of the $11 million sale itself will go toward things that aren’t helping housing affordability, the ostensible reason given for selling the land.

It appears Mayor Durkan currently has the support to pass the plan because four Councilmembers–Sally Bagshaw, Bruce Harrell, Debora Juarez, and Rob Johnson– have pledged support for the sale.

“Mayor Durkan’s proposal has strong support from the City Council because it will do what we’ve been trying to do for years: address the affordability crisis from many angles, moving people into and through managed shelter into respectful permanent housing,” Councilmember Bagshaw said in the press release.

“By funding new shelter and housing options and also including a payment to Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA), I am happy to see that these dollars would address both short and long term housing needs,” Councilmember Johnson added.

It’s interesting to see MHA contributions used to justify selling public land. Certainly the city extracts a benefit this way, but once land leaves public ownership it’s likely gone forever. Moreover, it’s a one-funding source and shelters and a rent voucher program would need a longer-term dedicated funding source to continue to make a difference.

“Leveraging one city property, we can provide essential services and attack our affordability crisis,” Mayor Durkan said in the press release. “There’s no quick or simple solution to solving this urgent challenge, but we can focus our efforts to rapidly deploy cost effective shelters to move people out of doorways and tents and into safer spaces.”

Temporary relief–rent vouchers, temporary shelters, and tiny homes on parking lots–is well and good, but, at the rate we’re at, a century from now we might look back and wonder where all Seattle’s public land went. Rather than selling off land to fund bridge housing, the more prudent move is likely to get additional affordable housing dollars elsewhere–whether an employee head tax, income tax, carbon tax, boosted housing levy, or anywhere really–and build on the land the public already owns. (Maybe we could even build on a city-owned golf course?)

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.