People tend to think of country music rather than urbanism when they think of Nashville, but Tennessee’s capital is plotting an urban transformation all the same. Nashville leaders hope to use a $5.2 billion transit package dubbed Let’s Move Nashville to achieve their aim. The plan calls for a mix of light rail and buses, both of which would use a 1.8-mile transit tunnel to cruise through downtown traffic. It’s funded primarily with a sale tax hike, but the city proposes to offer free or reduced transit fares to lessen the burden on low-income residents. The transit measure goes to ballot in May across Davidson County, which is contiguous with the city.

Let’s Move Nashville might not have gotten off the ground if its champion Mayor Megan Barry hadn’t prevailed in the 2015 election over her more fiscally conservative opponent David Fox, becoming Nashville’s first female mayor in the process. Mayor Barry’s platform is unabashedly pro-transit: “Let’s talk about my main priorities as Mayor: transit, transit, transit!”

Last year, Mayor Barry launched a Vision Zero campaign with a three-year action plan and promised to improve sidewalks, bike facilities, and street design to make zero traffic fatalities a reality. If she convinces voters to support Let’s Move Nashville, she may well succeed in leading Nashville down a urbanist path rather than staying on the meandering path of auto-oriented sprawl to a nowhere cul-de-sac.

Nashville is growing rapidly and surpassed 660,000 residents in 2016, according to US Census figures. Even so, the city sprawls out over 504 square miles, translating into a density of about 1,300 per square mile. By and large, Nashville has grown out rather than up. Mayor Barry’s transit plan would aim to channel growth along a rapid transit network, providing a framework to incubate density rather than feed more sprawl.

And it’s not just growth-minded leaders; Nashville residents have been clamoring for light rail, too. Erin Hafkenschiel, director of the Mayor’s Office of Transportation and Sustainability pointed to resident polls to demonstrate this support. “Overwhelmingly, Nashville residents said they wanted the light-rail options,” Hafkenschiel said, in an interview with City Lab’s Kristen Capps. “They wanted the go-big, the first scenario of light rail and commuter rail.”

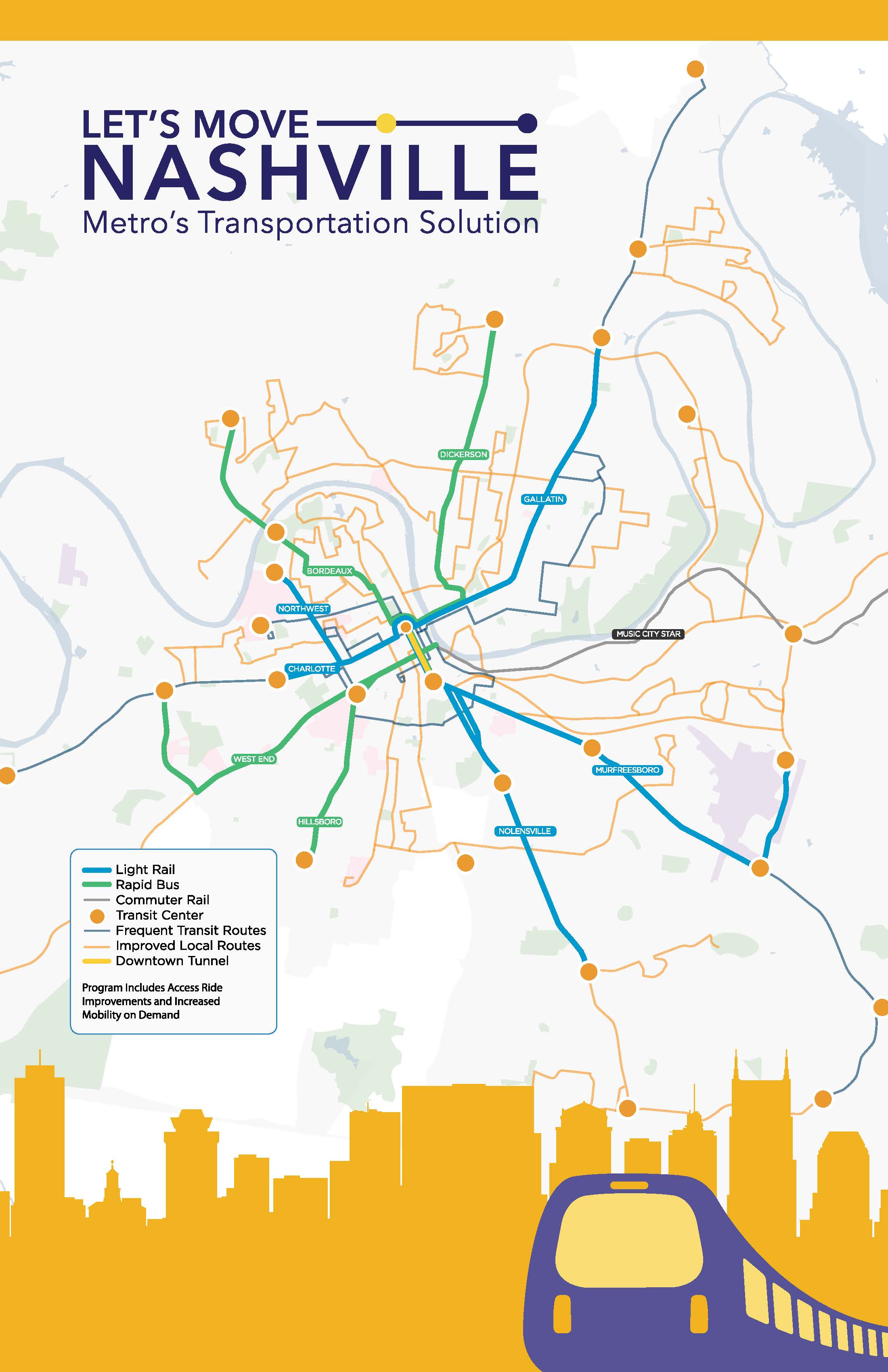

Going Big: Transit Tunnel, LRT, and BRT

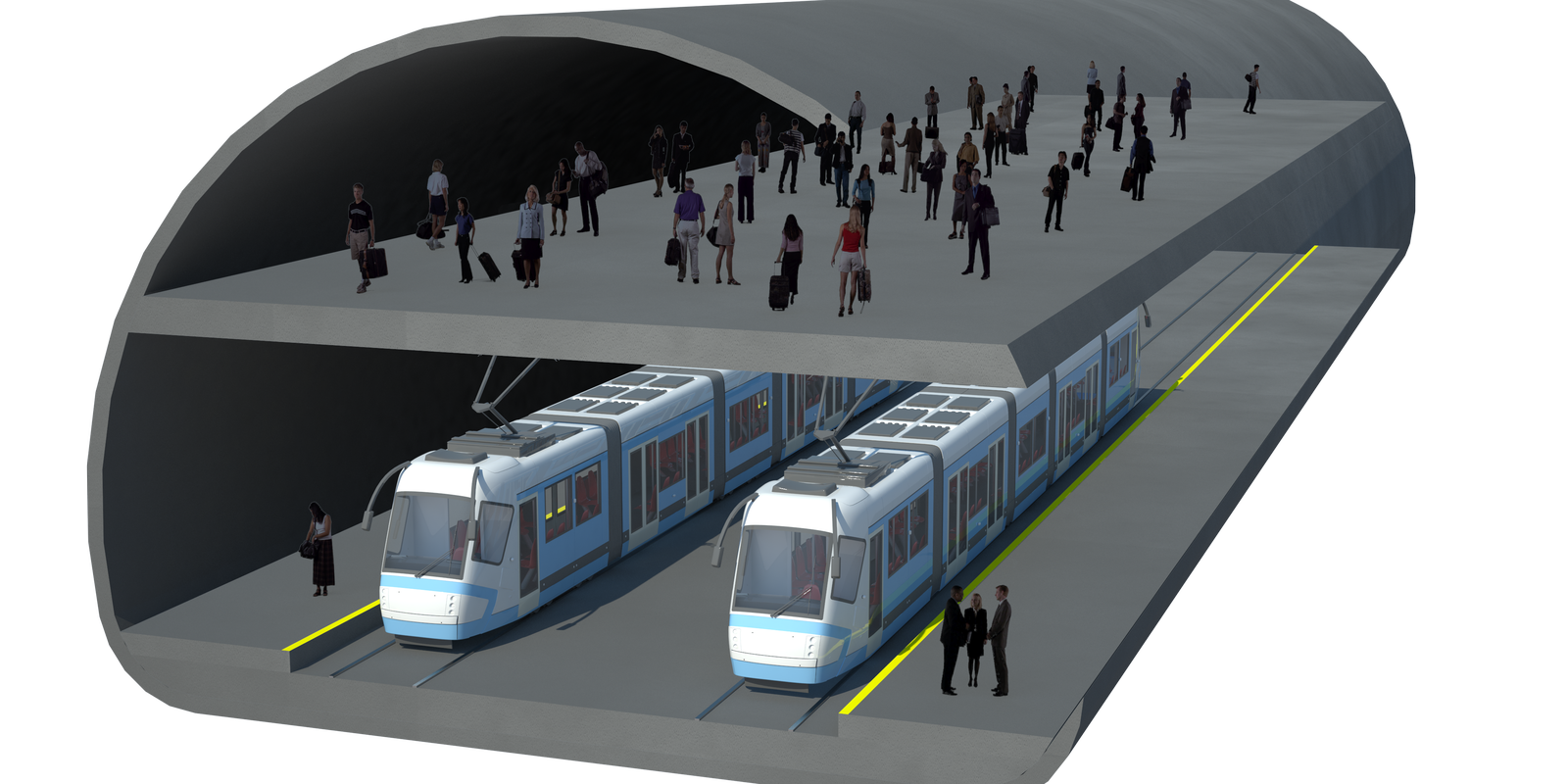

The downtown transit tunnel sets this plan apart. At-grade light rail lines radiate out from the central corridor, but using the downtown tunnel should vastly improve transit times over existing bus service.

Many transit agencies have made the mistake of ignoring downtown bottlenecks to the detriment of the whole network. For example, Portland’s streetcar network looks good on paper but the capacity, reliability, and speed of its lines continue to be hampered by the surface-running design downtown, which both forces delays at traffic lights and limits the length of trains to a city block. Minneapolis has also punted on dealing with downtown delays and instead queued up a series of suburban light rail routes. Even Dallas–a “metroplex” of 7.2 million people–is only now trying to build a subway tunnel to free its light rail network from downtown gridlock. Nashville is ahead of the curve as a metropolitan region of about 1.9 million. This ambitious vision might be why Nashville is a finalist to land Amazon’s HQ2 even without the massive tax break some other cities offered.

The transit tunnel would serve both light rail and buses, much like Seattle’s downtown transit tunnel does today (although Seattle plans to kick buses out before Northgate Link opens to improve light rail reliability). From the north-south downtown transit tunnel under Fifth Avenue, light rail and rapid bus lines fan out in all directions.

Five Light Rail Corridors

Nashville Metro Transit Authority outlines five light rail corridors totaling 26 miles in length:

- Gallatin Road — Heading northeast to Briley Parkway, this line provides “swift access to East Nashville’s growing neighborhoods, restaurants, and schools.”

- Murfreesboro Road — Heading southeast this line would connect Downtown to the Nashville International Airport (and points in-between) and use the transit tunnel.

- Nolensville Road — Heading south, the Nolensville Pike line would use the transit tunnel, stop at the proposed new soccer stadium, and terminate at Harding Place.

- Charlotte Pike — Heading west, the Charlotte Pike line would terminate at White Bridge Road.

- The Northwest Corridor — Sharing track with the Charlotte Pike line before branching to the northwest, “this LRT line will take advantage of existing rails to connect residents to jobs and opportunities in the corridor and around the city; as well as offer ready access to three of Nashville’s prestigious higher education institutions: Tennessee State University, Meharry Medical College, and Fisk University,” Nashville Metro Transit Authority said.

Four Rapid Bus Corridors

The agency promises that rapid bus corridors will include level boarding and off-board payment, which should limit dwell time. The plan also promises queue jumps and dedicated lanes “where feasible.” Four corridors (totaling 25 miles) have been identified for rapid bus service.

- Dickerson Road — Heading north “this quickly growing corridor for commerce will be more accessible from downtown to Briley Parkway.”

- Hillsboro Road — Heading southwest, this route would serve Vanderbilt University, Midtown, and Green Hills.

- West End Avenue – This route serves West End (makes sense) as far as White Bridge Road.

- The Bordeaux Route — This route heads northwest: “Travel all the way to Kings Lane along Rosa Parks Blvd, Buchanan Street, and Clarksville Pike with easy stops at places like the Sounds Stadium, Farmer’s Market, and the vibrant Buena Vista neighborhood in North Nashville.”

Timeline

Let’s Move Nashville wisely plans to deliver some bus improvements quickly out of the gates. Several local routes will get improvements and greater frequency. By 2023, rapid bus service will be operational in the four planned corridors. Ideally, that would grow the transit rider base as construction progresses on the tunnel and light rail projects–admittedly Nashville’s transit ridership isn’t very high today. Light rail is slated to start coming on line in 2026, with the whole network finished by 2032.

Affordable Housing

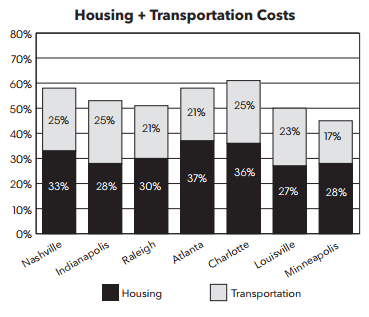

Mayor Barry’s plan includes an affordable housing strategy, and earlier this month the affordability task force she convened delivered its recommendations. Nashville’s prices haven’t seen the huge jumps like big coastal cities have and building housing at a rapid pace is part of why. Nashville built 11,203 apartments in 2017, which is just behind Seattle’s 12,008, with both in the top ten in apartment production nationally according to Real Page. On the other hand, transportation costs are quite high—eating up almost as large of a chunk of Income as housing costs for the average Nashville resident. That’s why vastly improving transit and adding reduced fares for low-income riders (as is planned) is a crucial step to making Nashville more affordable.

The affordability taskforce also made recommendations that address housing directly. The biggest ask is securing a new funding source to match at least 2% of the $5.2 billion capital investment, which works out to about $104 million. That fund would then leverage triple the investment to build affordable housing along the new high quality transit lines going in–perhaps using the land bank that is also proposed. The plan also calls for strategies to keep rents affordable for small businesses and create new small business opportunities along the transit corridors.

Nashville leaders have turned to Tax Increment Financing (TIF) as an affordability tool–Tennessee law preempts the adoption of inclusionary zoning or rent control. Tax increment financing would aim to funnel increased property values along transit lines into projects with affordable units in the same areas, counteracting displacement. The taskforce had this to say: “This TIF framework should be established well in advance of the transit development so that the market has the ability to incorporate this into the development pro-forma. It is recommended that, unless updated future market research and data strongly indicate otherwise, a minimum of 20% of residential development receiving public subsidy must be set aside for affordable housing.”

Will it pass?

Yonah Freemark gave a rundown of the transit package on Tuesday and acknowledged it may be a tall order winning over the electorate. Much like in Seattle, Nashville’s local media seems to be falling over itself to amplify transit skeptics. Freemark did a great job of debunking the arguments of an oft-cited Vanderbilt economics professor who simultaneously argued Nashville’s transit would not be used and would cause gentrification. Go figure!

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.