The early 1800’s were terrible times to be a British peasant. Parliament had been steadily granting landlords’ requests for enclosure since the 1500s, fencing off common land used by peasants for communal subsistence gardening. The landlords got a great deal; the newly vacant land could be used to produce more commodifiable goods (usually wool, but also minerals). The peasants were not as lucky. Stripped of their homes, communities, and food, the dispossessed were forced to sell themselves for subsistence. Many showed up starving and desperate for wages on the streets of the booming industrial and port towns.

British cities at the time were not healthy places. Laborers as young as five, working nearly 3,600 hours per year by 1840 (compared with 1,440 in the 1300s), faced severe injury or death working 16-hour days in the factories. The average life expectancy in towns like Manchester was 20 to 30 years lower than the countryside.

Faced with sudden explosions in homelessness and debt, Parliament responded with a militarized criminalization of poverty. Countless people were swept off the streets and impressed into the British Navy. Others were shipped around the world to the American and Australian penal colonies, themselves nearly purged of their large indigenous populations by British and European imperialists.

The working class had little political recourse. Standing or voting for Parliament was restricted to landowning men–the very people responsible for so much working-class misery. Around 98% of the population was completely excluded from the political process. The world was being radically reshaped by the world’s richest with no concern for those at the margins.

Fast forward to Seattle in 2018 and we have the same problems: an exploding homeless population that regularly endures forced eviction, powerful corporate developers vacuuming up city blocks and public land, entire communities being displaced, a global environmental crisis, and governments that remain unresponsive to the most marginalized communities’ needs.

If we are to address these problems in a meaningful way, we must first recognize that these problems are neither unique nor isolated. Rather, the conjunction of massive racial and economic inequality, global climate breakdown, and widespread housing crises are all parts of the structural crisis of globalized neoliberal capitalism. The system isn’t failing; it’s operating exactly as designed.

Supply or Demand?

Take housing. In King County, the unhoused and housing insecure population is over 10,000 strong. According to market logic, this must signify an absolute housing shortage. In fact, the opposite is the case–as of December 2016, there were over 200,000 empty bedrooms in King County. Most of these are in single-family homes in outlying areas far from job markets and without good transit (by design), but many are not–Capitol Hill’s echo-y mansions could easily fit more people. Amid this flush supply of empty bedrooms, prices for even leaky century-old houses with lead pipes are skyrocketing.

Of course, this argument is not complete. The market-based argument counters with some variation of “people want to live in vibrant places,” which is true, but generally contradicts market theory. The physical demand for housing is most acute for the 51% of Seattle tax filers who earn under $50,000 per year, yet the only housing being built is structurally unaffordable. Existing housing prices are kept massively inflated by speculation. And the strongest defense of the current system is, essentially, “rich people have high demand for culture”.

That culture is usually created by people who need cheap housing–people of color, queer communities, artists, writers, students, etc. Gentrification can be interpreted as commodification and extraction of that culture, to be accumulated by landowners in the form of exorbitant rent. Often this process includes displacement of those low-income, cultural communities, leaving only token allusions to the former residents–like rainbow sidewalks or indigenous placenames. Under contemporary late capitalism, living in “the gay neighborhood” or “historic neighborhoods” is another wealth signifier magically worth an extra $500 in rent or $50,000 in house value, not unlike the garish and confusing features of your average McMansion. And that doesn’t even touch the rooftop barbecues.

Housing is a Structural Crisis of Market Capitalism and Landlords Like It That Way

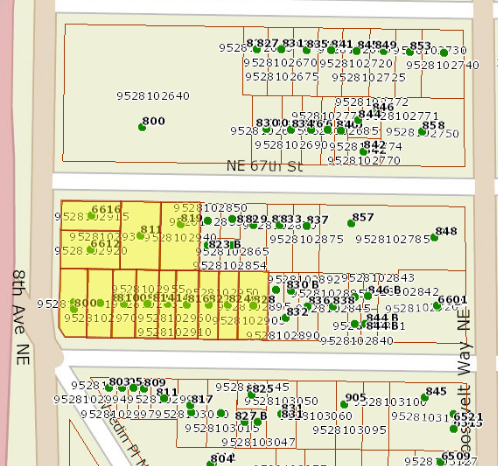

Inflated housing value would be bad enough if it were isolated to small, individually- or family-owned structures like detached houses. Land consolidation by corporate developers is much more pressing. Take Roosevelt Station, scheduled to open in 2021. The City has been allowing large companies to purchase entire blocks near the station–often a dozen individual lots or more–to construct single buildings on the newly huge plats. Most of the housing in the station’s walkshed–a few thousand units, at least–is owned by a small handful of investment firms.

This pattern is nightmarish–and not just because tower- and block-scale construction may not even lead to appreciable walkability or density. Instead, it is a large-scale concentration of power and land ownership in a time of skyrocketing inequality.

Just like the Industrial Revolution-era British landlords, Seattle real estate investors are primarily interested in making lots of money. Renters’ and landlords’ interests are diametrically opposed–renters want cheap rent with the opportunity of ownership (i.e., a path to not paying rent at all); landlords want permanent rent-paying tenants who will pay ever-growing rents. In this sense, housing is an extractive industry like fossil fuels or old growth logging–only the resource being extracted is our financial livelihood.

Housing is also a growing battleground in modern class conflict. Seattle is quickly becoming a town of perpetually impoverished renters subjugated to a rentier class that owns a growing share of the city’s land and housing. Meanwhile, housing insecurity is feeding the ballooning unhoused population that faces arbitrary forced eviction by the police state and slashed social services.

At the base of the housing debates in Seattle, we must recognize that this land was all violently stolen from indigenous people by an earlier generation of extractors. Today Seattle has a large population of indigenous people who are disproportionately unhoused. In other words, the ancestral stewards of this land are more likely to be kicked around by “private owners” whose only attachment to the land is value extraction.

Talking Solutions

Any sustainable urban policy–housing, transportation, food production–is doomed to fail without a robust human rights agenda. This cannot be done without challenging the market system and the commodification of essential human rights–both inside and outside formal political institutions.

The biggest obstacle to solving this crisis is breaking through the narrow logic of market capitalism. Under this regime, housing and land are commodities to be traded on the global speculative market. As is the case in Seattle, this often has little bearing in the real economy. Housing is seen as a financial investment to maximize profit (extracted in the form of rent) from as many housing units on as much land as possible. This type of logic is blind to issues of land use, pollution, and human or environmental suffering. Forgoing the twisted profit imperative–and challenging the concept of ownership itself, to the point of “rebuilding the commons”–opens up a wider set of options.

Two promising structurally affordable housing models are gaining in popularity: limited equity housing cooperatives and community land trusts. Both models are based in collectively owning and/or managing housing and land. In the cooperative model members own all property collectively and individually have the right to occupy their unit (typically in a building). Community land trusts own land in common and own their individual unit (typically a house) separately. In both models, the sale prices of units are controlled in some way to ensure continued affordability over time.

The unifying features of these models are collective ownership, stewardship, and direct democracy. In effect, this allows for residents to share housing costs and takes housing off the speculative market. More importantly they offer affordable long-term housing options, a supportive community, and meaningful decision-making power. To challenge the power of extractive landlords, we must build collective power to take control of our own land and housing.

These cooperative, community-owned institutions are already in place throughout the region – and the work they are doing is far beyond the scope of investment firms. A favorite is the Lopez Community Land Trust on Lopez Island. They have constructed six housing projects on Lopez Island–most are net-zero energy and include permaculture gardens, all at relatively low cost. How many Vulcan buildings are net-negative energy permaculture structures?

Challenges and Potential

Barriers to widespread cooperative housing remain. The largest is financial; despite the growing number of Seattle rental cooperatives (where the house/structure is owned by a landlord), piecing together enough money for buyouts is difficult.

Most community land trusts rely on long fundraising campaigns and financial partnerships with other organizations, much like the Africatown/Forterra project announced last year. Individual organizations get creative–Lopez CLT often draws skilled community members to volunteer labor, for example. Some generous folks have even donated houses to land trusts for almost nothing. And local credit unions, such as Verity, have begun discussing loan options to cooperative and community-owned projects. Still, the financial difficulties are pressing.

The work of building resilient social infrastructure is nearly as tough. Functioning cooperatives are built on social cohesion and trust–two things that get short shrift in America. Building small ‘D’ democratic structures and sharing arrangements can be tricky, as anyone who has ever had an argument over dishwashing knows. Luckily, there are plenty of cooperative veterans and resources centers (like the Northwest Cooperative Development Center) eager to share knowledge.

The work is rewarding, though, particularly for those traditionally disempowered by the racist global market economy that exploits indigenous people and communities of color. Cooperative ownership can allow folks to build wealth–in the economic and social sense–while reconnecting to each other and the land. It’s not inconceivable for such community-owned projects to be key parts of reparations for Indigenous and African-American groups. Indeed, these cooperative economies are thriving in places as disparate as Chiapas, Mexico and Emilia-Romagna, Italy.

Taking the Right to the City around the world

Of course, none of these patterns are new. Displacement and rebuilding of the city has been used as a tool by the powerful for centuries, much like the 1800’s British landlords. The popular phrase “the Right to the City” captures the fierce resistance to gentrification; first coined by sociologist Henri Lefebvre in 1968, it has been put by anthropologist David Harvey as “far more than the individual liberty to access urban resources: it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city.” It is a fundamental challenge to the status quo political economy of a city by and for technocrats and the global ultra-rich; it is a cry for collective self-determination by the most disenfranchised being taken up around the world.

Barcelona faces many similar problems as Seattle. Barcelonans endure crushing rents and endless waves of exploitative tourism—another form of gentrification. The radical grassroots movement Barcelona en Comu swept into the city government in 2015, less than a year after its founding, capturing 25% of the city council and putting housing organizer Ada Colau in the Mayor’s office. The party’s core is radical participatory democracy and rebuilding the public sphere after decades of privatization, including expanding public housing and the region’s thriving network of cooperatives.

Cooperation Jackson has similarly reshaped Jackson, Mississippi. The organization is a wide network of housing, food, and worker cooperatives built on social and environmental justice principles–a tall order in the Deep South. A prominent organizer with the organization–Chokwe Antar Lumumba–was overwhelmingly elected to the mayor’s office last year.

At home in Seattle we have seen an explosion of groups fighting for these same principles. The prominent Housing For All Coalition has secured a string of political victories since kicking off last year. And at the City’s latest hearing on the Fort Lawton redevelopment, hundreds representing organizations from the Seattle Democratic Socialists of America to tech solidarity organizations came out to push for affordable housing. Our own Right to the City movement is taking off in front of our eyes.

The main lesson from these movements is that rights to housing, to the city, to a healthy community and environment are won through major grassroots mobilizations and deliberately building resilient social infrastructures. When we realize our collective power, we can change the world for ourselves and our communities. Given the scale of suffering caused by this structural crisis of capitalism, we must build and wield that power–because billions of lives depend upon it.

Bob Kaminski is an organizer with the Seattle Neighborhood Action Coalition.

Further Reading:

The Right to the City: A Verso Report by various authors (Verso Books, 2017)

Jackson Rising: The Struggle for Economic Democracy and Black Self-Determination in Jackson, Mississippi by Kali Akuno and Ajamu Nangwaya (Daraja Press, 2017)

Governing The Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action by Elinor Ostrom (Cambridge University Press, 2nd ed. 2015)

Ostrom in the City: Design Principles for the Urban Commons by Sheila Foster and Christian Iaione (The Nature of Cities, 2017)

Social Ecology: Communalism Against Climate Chaos by Brian Tokar (ROAR Magazine, 2017)

Seattle Booms Because Amazon Is The Master Of Platform Capitalism