We shape our cities, and afterwards our cities shape us, to paraphrase Winston Churchill. In this, he eloquently drew a line between the built characteristics of our surroundings and the social outcomes they promote. Winston would no doubt feel vindicated though probably saddened to see that over the intervening years his assertion has been backed up by a wealth of research that confirms some built form characteristics are linked with high levels of stress, lower propensity to be active and social stigma amongst other things. These bring with them real, largely predictable problems that stifle lives: greater vulnerability to diabetes, heart disease, obesity, mental health problems, alcohol and drug abuse, and violence. The causes of this are many and their interplay complex and extend far beyond just the way cities are designed. However, “there is a reciprocal relationship between urban social conditions and the built environment,” according to Dr Sharon Friel.

For those adversely impacted, these impacts echo through generations as children grow up without personal, family or community experience of attainment or opportunity. They are often exposed to high levels of contaminants and the evidence of the world around them suggests no alternative but to resign themselves to a diminished life. They are separated from positive experiences and exposed to negative ones to lead shorter, less healthy, more isolated, and more stressful lives. They are denied the opportunities to explore and expand their abilities to develop their latent skills and realize raw talents. Thus they are deprived of a shot at fulfillment and we are all denied their contribution.

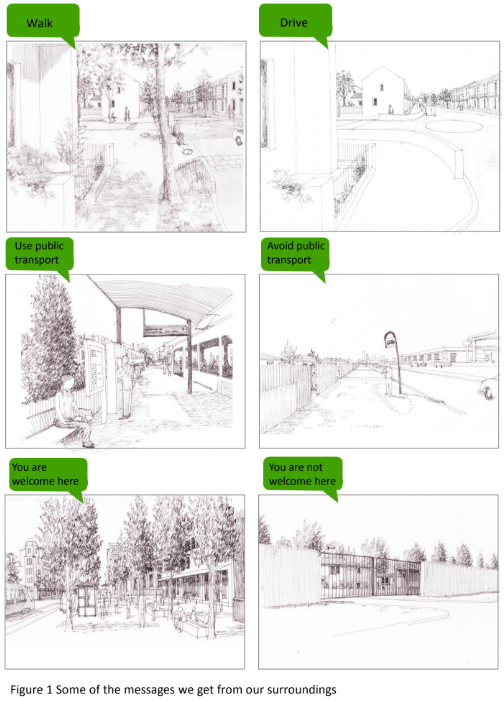

This is a tragedy and injustice of the highest order. Yet despite the tireless commitment of many civic-minded people in government and civil society who have sought to address this problem such deprivation seems endemic in our towns and cities. I would like to suggest a way of looking at this problem and potentially help to address it is to look at our surroundings as we looked at food and thought of cities in terms of how they nourish us. With this perspective a good city offers a broad ‘experience menu’ of activities and choices that nurture their inhabitants (allowing them to walk, be active, engage with each other, co-operate, etc) (figure 1) and those people can chose from that menu the experiences that matter to them personally (their experience diet) so they can self-determine their own, best way to meet their needs, thrive, and fulfill their potential.

Unfortunately, human beings are often not good at prioritising our needs. Even though we know at one level that getting out and about, having exercise and interacting with people is good for us, if our surroundings make these things difficult, some of us will overcome these challenges but many will find these physical and social barriers prohibitive. For many it is easier, feels safer and is way more familiar to stay at home and watch the TV. We choose to drive rather than walk, even when walking is a reasonable alternative we choose indoor screen-based play rather than be active outside. We consume sport on TV rather than playing it ourselves. Thus it is not enough just to provide opportunities to do healthy, nourishing things, we need to tilt the balance of influences so people want to do the things that best support their health. Thus the compassionate city serves fries but the salads are nicer.

That’s where good urban design comes in. Urban designers can tailor our surroundings to make nurturing behaviours like being active, sharing space and activities and experiencing nature (amongst other things) more appealing and get from the experience menu to our experience diet. This then raises the question how should designers wield their pens to achieve this outcome? I was lucky enough to have the opportunity to address this issue and document my observations in “Designing the Compassionate City” to be published in early 2018 by Routledge. This book revealed that in addition to the well-known spatial qualities readers will be familiar with (also covered in the book) there are a number of key recurring themes that might be just as important in creating nurturing places.

Some of these themes are:

Changes in hearts and minds are as important as those on the ground. Experiences may go from the experience menu to our experience diet by either by changing the place or the way it is interpreted. Sometimes all that needs to happen is for people to look on their surroundings differently; giving greater weight and value to the things that facilitate them to meet our needs and diminishing the weight they put on the things that distract or deter them from meeting these needs.

Design out appropriation. Nurturing places control uses that can overwhelm beneficial experiences, seeking to balance uses and minimize intrusion. A good example of appropriation are the busy roads that blight pedestrian life on the adjacent sidewalks and an inspiring example of overcoming it are the woonerfs of the Netherlands that cater for vehicles but don’t allow them to dominate the street, allowing play, socialization, and nature to escape the private domain and occupy easily accessible shared space (Figure 3).

Create adornable public spaces. These are spaces that serve a core purpose and contribute to our amenity just by being there, such as footpaths, parks, squares, and street furniture, but can provide us with a further level of delight and interest when they are being adorned by people for a wide range of self-determined uses. For example, features that offer the theater of the streets, that invite children to play, that invite adults to stay long enough to bump into someone else they know, that are enlivened by smiles, laughs, artworks, and just by occupation by others (see below).

Finally think ‘legacy’. Cities are complex biological and physical systems that are influenced by many people with many different agendas to take the city in a particular direction. With care we can change this momentum and foster hope and self-worth by giving people compelling evidence that walking, cycling, engaging with others is fun and by empowering them with new skills and insights so their ‘islands of competence’ might grow and coalesce. In this way offering experience of overcoming new challenges.

As you can see, these ideas don’t quite fit easily into the silos of policy or practice. Looking to provide people with a balanced and nutritionally complete balance of experiences that will be right for them may be challenging, time-consuming and possibly expensive. However, if doing nothing means towns and cities stay places that stifle many of their inhabitants’ human potential, with all that entails, then the question we need to ask ourselves shouldn’t be “how can we afford to make the changes necessary to design the compassionate city?” but “how can we afford not to?”

All images from Designing the Compassionate City by Jenny Donovan, published by Routledge 2018 and available at this link.

Jenny Donovan

Jenny Donovan is the Principal of the Melbourne-based urban design practice, Inclusive Design. She set up the practice to focus on and advocate for urban design that emphasizes improved social outcomes. Her work spans urban and landscape design, social and environmental planning, and neighbourhood renewal in Australia, the UK, Palestine, Ireland, Ethiopia, Kosovo, and Sri Lanka.