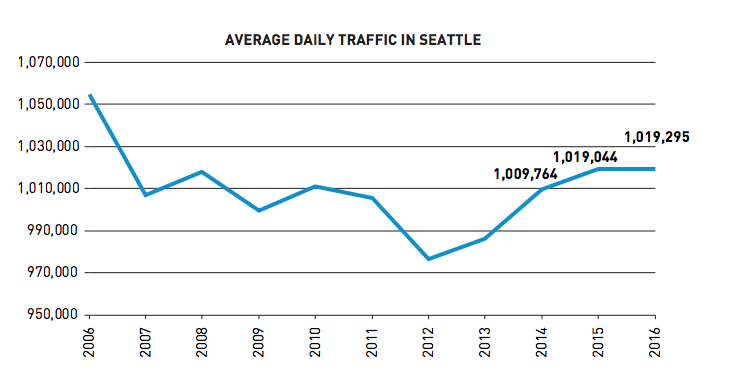

The Seattle Department of Transportation earlier this month released its 2017 traffic report, which finalizes a year’s worth of data from 2016 to provide a picture that can be comparable to previous years of data. One of the most notable conclusions from the report is that SDOT’s estimates for average daily traffic volumes in the city stayed completely flat, only increasing by 250 vehicles. Average daily traffic volumes had been declining prior to 2013, but had been trending upward since then. Traffic volumes staying flat overall fits within the trends we’ve been seeing earlier this year around downtown commuting: as we reported earlier this year, of the 45,000 jobs added in downtown Seattle since 2010, solo commuters downtown only increased by 5%, with the rest of the added commutes being added via transit, biking, and walking.

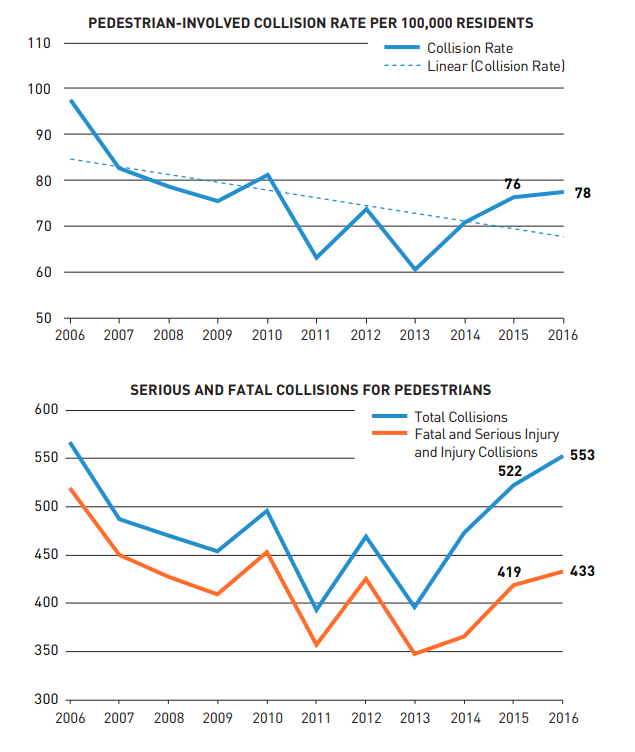

The 2017 traffic report also breaks down collision data, to provide a snapshot for year-to-year progress toward the city’s goal of eliminating serious and fatal injuries on our streets by 2030. But there’s also a danger of focusing too much on the trend line of collisions to find out if we’re making progress on Vision Zero: serious and fatal injuries are symptoms of the systemic problems that need across-the-board solutions. There are some areas where Seattle is making progress, but they are mostly few and far between right now. Worst of all are the trend lines for people on foot.

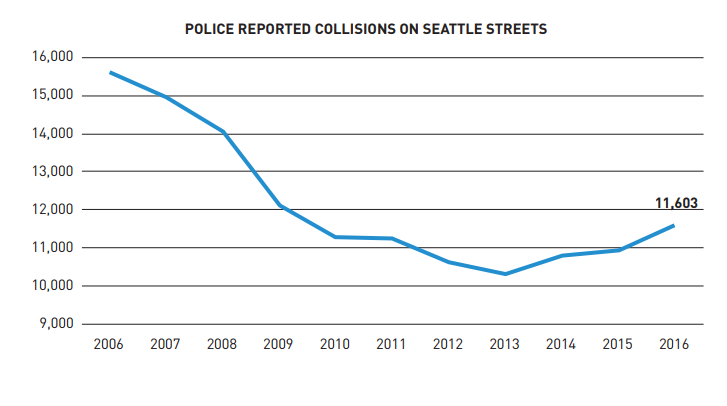

Collisions reported to the Seattle Police Department in 2016 were up for the third year in a row, generally following the trend of average daily traffic volume, and were at their highest levels since 2009.

But how are we doing preventing collisions involving vulnerable users from happening and, when they do, preventing serious injuries or deaths? In total number, the number of pedestrian-involved collisions in 2016 were at levels that the city hasn’t seen since 2006. There were 428 pedestrian-involved collisions in 2016 that involved serious injuries and five that were fatal.

From the data it’s clear that our streets are not improving for pedestrians: 2017 data, while not complete yet, provides more evidence for this. So far this year, 10 people on foot were killed on our streets, double the number from 2016.

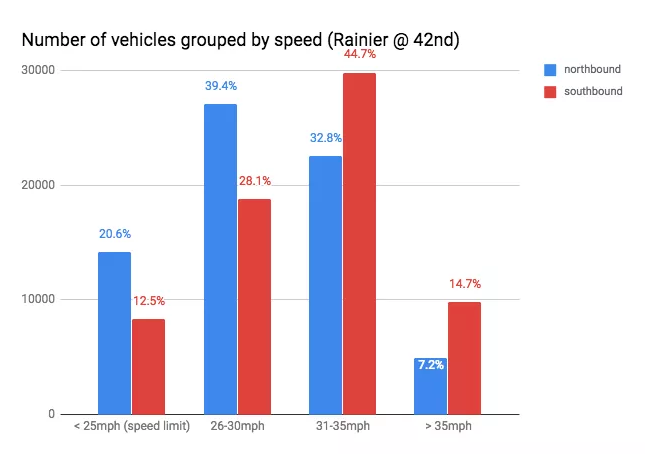

To stem the tide and make our streets truly safe, it’s not enough to hope that we are seeing a positive trend line in the data in front of us. We must demand system-wide changes to our streets. One of the biggest things we can do to both prevent collisions and ensure that they don’t result in serious injuries is to reduce the speed of drivers. Seattle’s city-wide changes to speed limits that took effect in 2017 will definitely play a part in getting some drivers to slow, but in most instances design changes are the true solution to speeding traffic: people drive the speed they’re comfortable driving.

Andres Salomon earlier this year crunched the data from Rainier Avenue (which in 2016 entered the ranks of the 10 busiest arterial streets in Seattle) after the road diet on a small section converted two lanes in one direction to one, adding a center turn lane. After lowering the speed limit to 25 mph from 30 mph, most drivers were still going way faster than that. A culprit suggested in that instance for drivers continuing to speed was the wide lanes along Rainier, as they were actually widened to 12 feet.

In northeast Seattle, NE 65th Street is a hotspot of collisions of all types: the changes proposed by SDOT include not adding any additional pedestrian crossings. A lack of crossings will encourage drivers to speed up between traffic lights, pitting them against pedestrians attempting to cross at unmarked crosswalks. In addition, drivers will encounter a wide travel lane at bus stops, allowing them to pass stopped buses, compounding a dangerous situation for pedestrians. Most people on foot are going to get the message: don’t cross, we’re prioritizing other modes here. What this street design does not do is create a situation where, in the event a collision does occur, injuries are not serious. Making these changes under the banner of Vision Zero is pretty problematic.

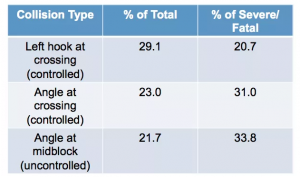

Late last year, I wrote about how SDOT had completed and was beginning to analyze its study of eight years of traffic collision data on vulnerable users, which they called the Bike and Pedestrian Safety Analysis (BPSA). The study identified several top factors involved in pedestrian collisions, like left turn movements accounting for 29% of total collisions.

By looking at what types of intersections see frequent collisions, safety changes can be applied broadly to prevent tragedies before they occur. And that’s exactly what SDOT signaled it was about to start doing: after the BPSA was completed, the department announced that it was changing the way it was prioritizing both new and improved traffic signals, based on collision data. They released a list of crash-prone intersections that they would be analyzing to add protected left-turn signals, where pedestrians and turning vehicles are not in the crosswalk at the same time.

At the end of 2017 most, if not all, of the intersections remain unchanged. This is the type of systemic change that will be needed across the entire city and we will need to act fast to achieve our goal by 2030. David Gutman at the Seattle Times identified the top intersections where pedestrians were hit in the past 10 years: a clear majority of the intersections listed included unprotected intersections.

It’s time for a systemic change in how we design our streets. Do that and the data will follow.

The featured image is by Alex Brennan/Capitol Hill Eco District.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.