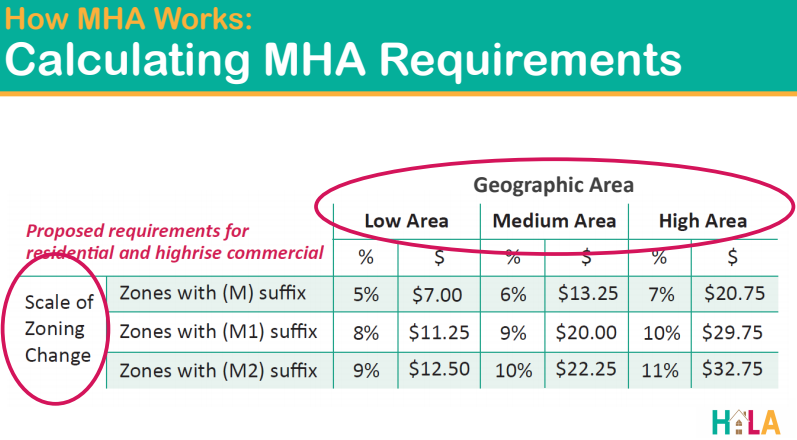

The Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) released its preferred alternative for the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) zoning changes earlier this month. Much was made of difference between Draft Alternative 2 and Alternative 3–which had a displacement analysis–but, for the most part, the preferred alternative sticks to the original framework: granting a bare minimum of one additional floor of zoning to implement the MHA (inclusionary zoning) requirements at an “M” level between 5% and 7%. As such, it represents a huge step forward taking MHA to every multifamily-zoned corner of the city while also signaling a missed opportunity to guarantee higher affordability percentages and greater housing capacity in transit-rich areas.

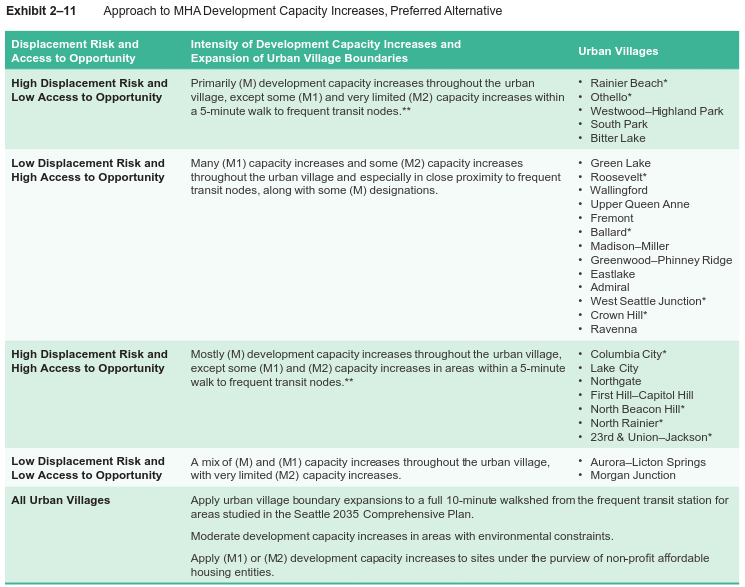

Granting larger magnitude upzones could have generated more instances of “M1” zones with requirements between 8% and 10% and especially large increases that generate “M2” zones with 9% to 11% requirements. The anti-displacement Alternative 3 could have conceivably meant M2 upzones in wealthy North Seattle urban villages (with low displacement risk and high opportunity) in order to lessen zoning changes in high displacement risk neighborhoods. In practice, the preferred alternative–though keeping some aspects of Alternative 3–keeps M2 upzones few and far between.

“High Access to Opportunity” neighborhoods that see no M2 zones include Capitol Hill, Upper Queen Anne, Interbay, Fremont, Northgate, Green Lake, Ravenna, Columbia City, Admiral, and West Seattle Junction. Capitol Hill, you may have noticed, just got a subway station last year. Northgate will get light rail by 2021, and West Seattle Junction will get its own $2 billion line by 2030.

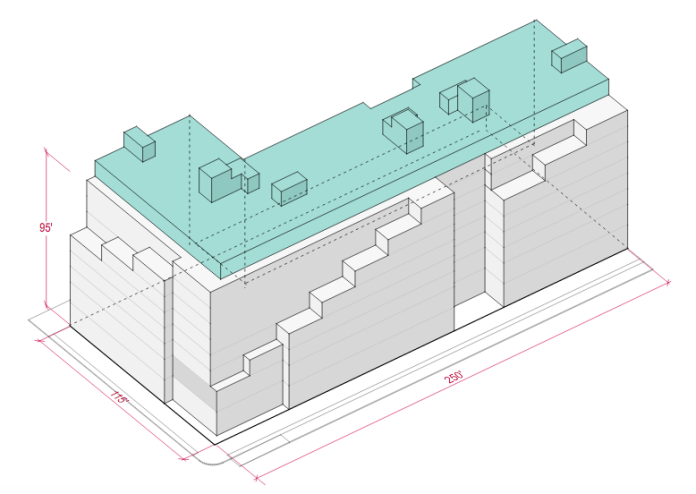

The lack of M2 zoning seems to relate by a shyness to implement highrise zoning in any neighborhoods that didn’t already have it, as I and many others had suggested. Neighborhoods like Capitol Hill and Ballard already had generous enough zoning that the only way to get to an M2 upzone mathematically would have been to go beyond midrise to implement a highrise zoning like Neighborhood Commercial 125 (NC-125) or NC-165. OPCD didn’t appear interested in taking that step this time around–even in Capitol Hill.

Other neighborhoods like Ballard, Madison-Miller, Crown Hill, Greenwood, East Lake, Morgan Junction, and Wallingford saw a block or two of M2 zones while mostly getting M upzones and a smattering of M1. Lake City, albeit a high displacement risk neighborhood, doesn’t even get an M1 upzone, let alone an M2. Same for Bitter Lake. While less intense zoning changes may mean less physical displacement, economic displacement (i.e., being priced out) is anybody’s guess. Neighborhoods forgoing M2 and M1 may miss the higher affordability requirements they bring.

This isn’t to paint too dour of a picture. M1 zoning were relatively more prevalent than M2 and its MHA requirement is just a 1% step lower at each level. For many, there was hope that High Opportunity Low Displacement Risk urban villages would relate more directly to M2 zoning in practice rather than mainly in theory. Reaching M2 from midrise might have meant following the Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda recommendation in Appendix E to merging NC-85 zoning into NC-125 in order to get to a more useful zoning that actually gets built out more frequently. Instead, we’re stuck with a lot of NC-95, which forces more concrete floors without providing much height to recuperate the greater costs associated.

We can certainly hope that as the opening of West Seattle Link and Ballard Link nears enough, OPCD will revisit zoning plans and do more to take advantage of these transit investments and guarantee more housing and affordability near the stations. For now, urbanists will have to content themselves with the framework for bigger changes being in place, even if M2 was used sparingly this time around. The M1 and M2 framework should come in handy down the line.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.