Awhile back I wrote about adding a RapidRide E rail line that continues to First Hill to Seattle Subway’s Vision Map, and the idea caught fire a bit. Seattle Subway proposed that by using rubber-tired metro technology, the project–which they dubbed the Magenta Line–could qualify to use the City Transportation Authority (CTA) since it uses a fixed guideway like a monorail does. Back in 2002, the State Legislature granted Seattle (or any city with a population exceeding 300,000) the ability to invoke the CTA with a majority vote in a ballot amendment.

It turns out to be surprisingly easy to get a CTA on the ballot. It’s as straightforward as the Seattle City Council voting to do so or a petition gathering enough signatures, Seattle Subway Executive Director Keith Kyle said. “The ballot measure can happen via council vote or by mind-bogglingly small amount of signatures–less than 4,000,” Kyle said.

CTA: Vestige of Monorail History

CTA’s intent was to provide a funding mechanism to expand the Monorail that could be activated by passing a ballot amendment. Seattle passed amendments in support of the Monorail four times, but, to make a long story short, the Seattle Monorail Project’s poor management and a lack of establishment support ultimately called the endeavor into question, and a fifth ballot measure failed by a wide margin. Assets were liquidated and the monorail dream was dashed, but, as fate would have it, the funding mechanism remains.

The City Transportation Authority statute stipulates that the taxing authority can be used for “a transportation system that utilizes train cars running on a guideway, together with the necessary passenger stations, terminals, parking facilities, related facilities or other properties, and facilities necessary and appropriate for passenger and vehicular access to and from people-moving systems, not including fixed guideway light rail systems.” The fact that a rubber-tired metro is not light rail presents an opening, although this interpretation would need to stand up in court.

What Is A Rubber-Tired Metro?

Rubber-tired metro systems are popular and widely used in Japan and in cities such as Paris, Montreal, Santiago, and Mexico City. Under this system, rubber tires on rolling pads propel the trains while traditional steel wheels on steel tracks provide guidance and a fail safe. Rubber-tired metros provide the advantage of readily handling steeper grades thanks to their greater traction–this advantage could prove pivotal for serving First Hill. Rubber-tired metro boast a smoother ride than conventional rail with less jostling. Faster acceleration and shorter braking times can also tighten up headways.

Some disadvantages of rubber-tired metros include higher energy consumption and higher maintenance costs, in part because rubber tires do not last as long as steel wheels. The more complicated trains also tend to be more expensive and run hotter. Running hot can be a major concern for a deep subway that is difficult to vent such as the London Underground. However, an elevated system would avoid the issue.

Fine-tuning the Magenta Line’s Route

- Use existing Monorail right-of-way on Fifth Avenue. Seattle Subway’s feedback on my proposal helped fine-tune a more advantageous routing. The big change is running the line on Fifth Avenue using existing Monorail right-of-way rather than on Second Avenue, which would have required expensive land acquisitions and numerous headaches. The stop at Harrison Street would offer a connection to the future Ballard Link station buried in the vicinity. From there the E could head to the Seattle Center connect with the Monorail right-of-way at Broad Street and 5th Ave N, and then it’s smooth sailing to downtown along Fifth Avenue.

- Use Madison and Union Street to serve First Hill and the Central District. The line would turn at Madison Street to make the climb to First Hill. Once in First Hill, the E could use E Union St to reach the heart of the Central District at 23rd and Union, adding only a mile to its length but greatly improving its usefulness and serving a community so far neglected by light rail.

- A mix of elevated and median-running on Aurora Avenue. Elsewhere, the route replicates the RapidRide E, except running in the center, elevated as need be. Some portions, like the uninterrupted stretch between Harrison Street and N Winona St, would not need to be elevated, except at stations. Elevating station allows more spacious stations, separates riders from Aurora Avenue traffic, and provides a new pedestrian crossing.

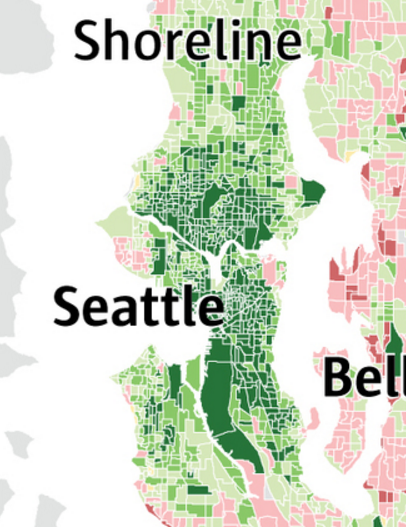

ST3 election results by precinct. (Kelly Shea/The Seattle Times) - Stopping near Aurora Village Transit Center. A terminal could be located at N 200th St, as the RapidRideE does, assuming Shoreline joins and approves the measure. Using the Monorail authority would likely happen at the municipal level. If we wanted to continue the E line through Shoreline, then our neighbor to the north would also have to greenlight the line in a city vote. It seems likely Seattle would support adding a new rail line–particularly one that could finish ahead of some ST3 projects–but Shoreline is less reliably pro-transit. Still it is relatively pro-transit for a suburb and did support ST3 by a healthy margin, as you can see by the map by The Seattle Times.

- Keep urban stop spacing. The downside of upgrading a bus line to rail is that rail lines typically have fewer stops. This does allow faster end to end times. However, we want the walkshed to emanate fairly continuously from the route since most of the area is either already dense or zoned to get there. The benefit of running above ground in state-owned right-of-way is the stations shouldn’t be expensive, especially compared to underground lines.

- George Washington Bridge. An obstacle for getting the Magenta Line to work is figuring out how to cross the Fremont Cut. The simplest way would be to just use Aurora Avenue’s existing crossing: the George Washington Bridge. Unfortunately, the 1931 bridge may not be up to the strain of adding tracks and trains. Determining that a new crossing is necessary would have a large effect the total price tag.

Strategy Going Forward

Kyle warned against unrealistic expectations when pushing another big transit initiative such as funding the Magenta Line with CTA.

“Getting everything lined up to actually win a ballot measure while not suffering the same fate as the monorail (we will need establishment support) will be much more difficult,” Kyle said. “I’m thinking of a 2024 measure and we’ll have to start working on the idea by next year, essentially.”

Nonetheless, diligently laying the groundwork can pay off in time.

“If this process has taught me anything, it’s this: It takes years for people to get used to an idea and years more for it to become inevitable enough to actually happen,” Kyle said.

Perhaps we will get to a place where a metro on Aurora and Fifth Avenues and Madison Street feels inevitable. For now, the battle for support and legitimacy continues.

A CTA Route for Tacoma and Spokane

If Tacoma and Spokane were to get ambitious about building out their transit with a rubber-tired metro, they would qualify to use CTA if they gained about 85,000 more residents. That would have sounded far-fetched before our latest boom, but Tacoma is growing steadily, gaining about 20,000 residents in the last decade. Or to take a less patient tact, either city could go on an annexing kick to get over the 300,000 mark. For Tacoma, it could prove one of the more viable ways to expand on ST3.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.