Some vocab first:

- MHA – Mandatory Housing Affordability; Seattle jargon for inclusionary zoning.

- Inclusionary Zoning – This is the common term for MHA; it requires new development to either include subsidized housing units or pay into a fund that helps pay for subsidized housing units to be built elsewhere.

- HALA – Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda; the 65-point plan to address housing affordability in Seattle developed by a committee formed by ex-mayor Ed Murray and released in 2015.

- Linkage Fees – Similar to inclusionary zoning except the inclusionary part — meaning including subsidized units on the same site as new development is not emphasized.

- Hard Costs – The on-site portion of development costs including construction labor and materials.

- Soft Costs – The off-site portion of development costs including professional labor (like architects) and development fees.

- Variance – The expected deviation from an average, but squared so that larger deviations have an outsized effect.

You’ve probably read an article like “Six possible solutions to fix the affordable housing crisis” that pop up every few months. They’re typically a hodgepodge of recommendations including zoning deregulation, tenant law tweaks, tax incentives, and European design imports. I’m happy this subject is getting so many column inches but I am also disappointed.

I’m disappointed because the recommendations are made up of isolated policies that fail to address the root cause of the affordable housing crisis: demand (particularly the way demand betrays neo-classical economics in urban spaces). This is the “multi-pronged approach” of the “complex problem of housing affordability” where the prongs are all pell-mell and the problem is misunderstood. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t supply-side solutions to the housing crisis, too.

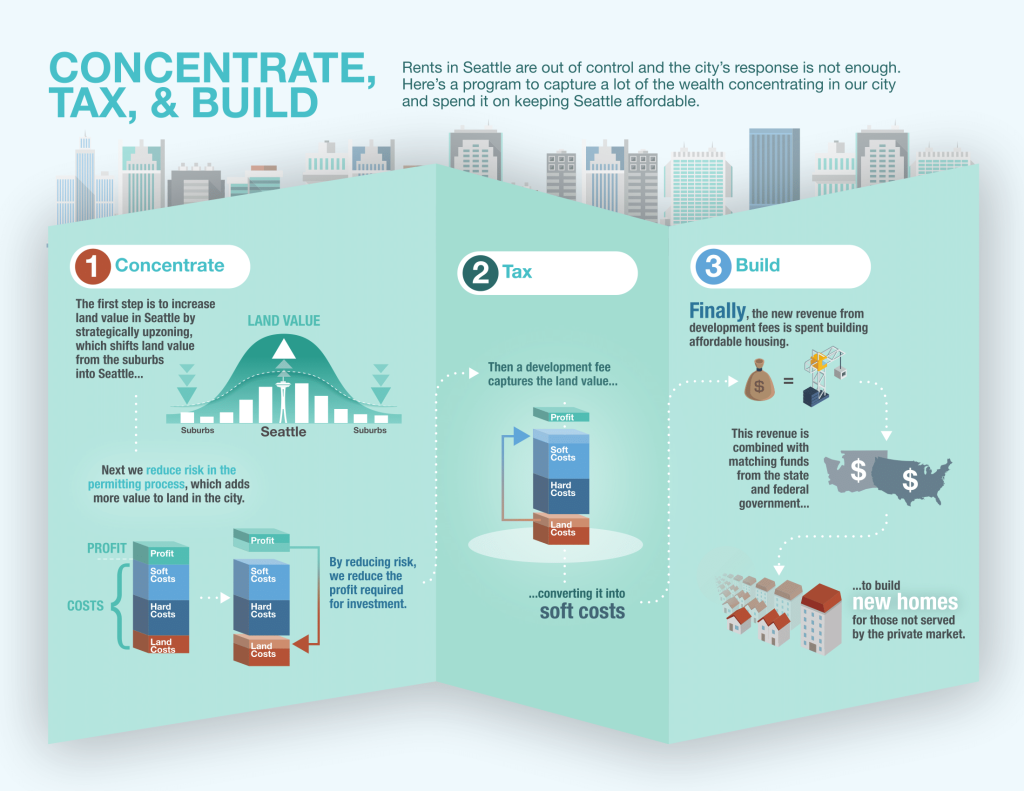

I’m proposing a four-point platform that works on both sides of the housing market — supply and demand. On the supply side, it concentrates value into urban land, captures that value through development fees, and funnels those fees into subsidized housing supply — a concentrate, capture, and build program. On the demand side, it taxes high incomes that drive the price of housing skyward. Together, this is the core of the most effective affordable housing platform.

In Seattle, the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA, but also better known as inclusionary zoning) program — the centerpiece of the 65 HALA recommendations — combines upzones with inclusionary zoning. MHA represents former Mayor Murray’s efforts to appease both for profit and non-profit housing developers with 6,000 affordable, rent-controlled units alongside upzones throughout the city (and the implicit agreement to not pursue Councilmember Mike O’Brien’s linkage fee proposal from 2014). It is a compromise, surely, and its modestly-sized proposals (in a nutshell: modest upzones for the for-profit developers paired with single-digit inclusionary zoning rates for the non-profits) have left an opening during this campaign season to dream bigger. The question is, can the dream of a more affordable Seattle be made real? Or, must we content ourselves with small barricades from overwhelming market forces — lest we make things even worse?

Seattle City Council candidate Jon Grant and former mayoral candidate Nikkita Oliver have made 25% inclusionary zoning a central policy plank of their campaign platform. But, as Grant admits on a post to his website, “[c]urrently, not every neighborhood or project in Seattle will be able to absorb a 25% requirement.” Specifically, there might not be enough value in the land to absorb 25% inclusionary zoning. Typically land makes up about 20% of the value of new residential development and less for larger commercial projects. It’s this gap — between the land value percentage of new development and the percentage of inclusionary affordable units required that ought to give everyone pause1.

I’ve made the case previously that development fees like inclusionary zoning or linkage fees, when proportional to land value and telegraphed to the developer prior to buying land, are actually paid for by landowners. This idea is anathema in many urbanist circles but not to people who study land economics and policies. So it’s worth taking a detour to repeat a couple quick summaries of the inclusionary zoning research before moving on.

“Policy makers are understandably concerned that affordable housing requirements will stand in the way of development. But a review of the literature on the economics of inclusionary housing suggests that well-designed programs can generate significant affordable housing resources without overburdening developers or landowners or negatively impacting the pace of development.” – Lincoln Land Institute

“Critics often claim that inclusionary housing policies are not effective at producing affordable housing and have negative impacts on local housing markets. However, the most highly regarded empirical evidence suggests that inclusionary housing programs can produce affordable housing and do not lead to significant declines in overall housing production or to increases in market-rate prices.” – Center for Housing Policy

And, if your interest in the research is piqued you can go straight to The Urbanist’s collection of interviews with the researchers themselves.

So, that 25% inclusionary zoning rate Grant and Oliver have proposed wipes out most if not all of the land value in a typical new residential development, threatening the feasibility of residential development. We can either stick with single-digit inclusionary zoning, grateful for the 6,000 rent-controlled housing units in 10 years projected under the current plan, or we can put a lot more value into the land — through strategic upzones and purposeful policy reforms — and build roughly four times the number of affordable units2. This is the same “four times” figure mayoral candidate Cary Moon has called for, we just get there in different ways.

Seattle residents have suffered through skyrocketing rents for the last several years with little relief from their government. So it’s not surprising that affordable housing has become a central campaign issue during this election season. This is a ripe time to present a straightforward affordable housing platform that works economically and politically. It responds to renters’ and housing activists’ complaint that MHA doesn’t do enough. It responds to homeowners’ complaints that MHA asks for too much neighborhood disruption for too little affordable housing. And it responds to the politicians who want something that works legally and economically and can pass council.

If you think the city’s response to the housing crisis falls short, then this is the platform for you.

The Present Affordable Housing Crisis Is Not the First but It Is Exceptional

(If you’re just interested in the policy platform, skip this section. But I’ve read enough articles minimizing the size of the affordable housing crisis that I thought it’s worth another detour to justify a robust response to the present crisis.)

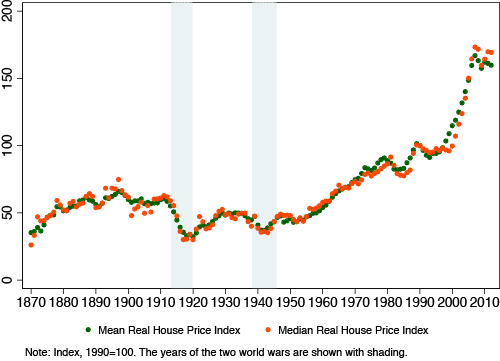

Our present crisis of affordable housing in cities is not without precedent but beginning in the 1990s, with the rise of the global information economy, the size of the crisis stands without parallel in the modern era.

14 unweighted inflation-adjusted house price indices from “Home prices since 1870: No price like home,” Center for Economic and Policy Research.

The late 19th Century in the United States saw dramatic housing price increases with urbanization, notably from European immigration and the decline of agricultural employment. Urban population and, to a lesser extent, wages, the two key components of housing demand, rose, and so did tenement housing. But the ballooning demand for housing was tempered by the rise of new transportation systems — streetcars, trains, elevators — that effectively expanded the volume of developable land, bringing new land into use as housing just as urban populations boomed. Since the 1990s, however, global capital has increasingly concentrated in cities with the rise of professional service industries like banking, insurance, and law that depend on personal interaction and a variety of support services only cities can provide. In the years that followed no transportation revolution was available to match expanding urban demand with expanding urban land3. Yet the concentration of capital in cities continues. Today you can add tech to the list of high-wage industries that are moving into cities, all while wages outside these industries have remained stagnant for decades.

The size of the affordable housing crisis is so large that any serious affordable housing platform ought to be potent enough that it threatens to overwhelm other systems in the city — schools, water treatment, transit services. I don’t know if 2,000 or more additional units of housing a year does that, but among feasible proposals to address the affordable housing crisis it gets the closest.

The Four-point Affordable Housing Platform

1. Concentrate regional development in Seattle by increasing zoning capacity, especially through zoning that favors dense but relatively affordable construction (e.g., rowhouses, duplexes, and other “missing middle” typologies).

Seattle has been increasing its zoning ever since the Growth Management Act required it to have enough “buildable lands” for 20 years of projected growth. The buildable lands metric measures potential number of housing units in a city allowed under law but it doesn’t specify what type of housing units. And so Seattle has flirted with and sometimes enacted policies that decrease types of housing while at the same time zoning for greater total housing units. This is a deficit of the Growth Management Act but it shouldn’t preclude Seattle from taking the lead and developing its own buildable lands report that emphasizes the building types that have historically provided urban housing for the “poor, young, and single.”

Alan Durning, of Seattle’s Sightline Institute, wrote a book, Unlocking Home, on just these types of buildings that were prevalent in Seattle’s pre-war era but which have since nearly disappeared. He writes in a Slate article summarizing the book,

“Most Americans live in houses or apartments that they own or rent. But a century ago, other less expensive choices were just as common: renting space in families’ homes, for example, or living in residential hotels, which once ranged from live-in palace hotels for the business elite to bunkhouses for day laborers. Working-class rooming houses, with small private bedrooms and shared bathrooms down the hall, were particularly numerous, forming the foundation of affordable housing in North American cities.”

In addition to the single-room occupancy housing that has nearly disappeared (except for college students), there is a whole set of more familiar building types that have and could provide housing for middle- and lower-class families for whom downtown towers and well-appointed townhouses have been out of reach. These include rowhouses, courtyard apartments, duplexes, triplexes, mother-in-laws, and dingbats: lowrise housing that provide a lot of options at a (relatively) low price.

Allowing more housing types is a benefit in its own right, but it is also an important piece in the larger strategy of maximizing the value in land so that it can be captured through programs like inclusionary zoning. Upzones may not dramatically increase regional housing supply because it likely moves housing production from one part of the region (suburbs) to another (city) but it at least brings the environmental and health benefits of urban living even if its affordability benefits are more questionable. It does indirectly benefit affordability, however, by concentrating regional land value in city land, making it available for a land value capture scheme like inclusionary zoning.

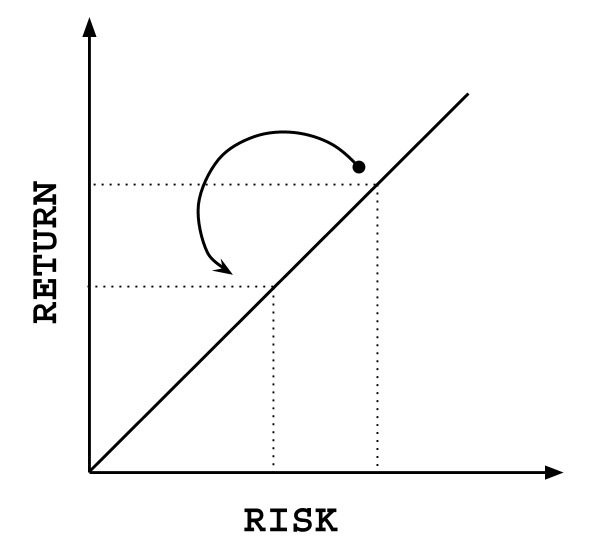

2. Reduce risk in the permitting and land use process by reducing the variance of approval or rejection of similar projects.

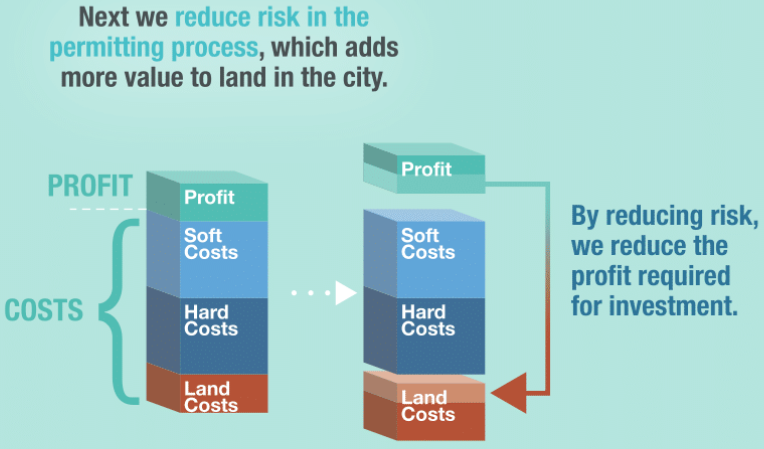

Wealth can be further concentrated in land by going after risk in the permitting process.

Clear outcomes in the permitting process reduce risk. Reducing risk reduces cost because as risk goes down, average profit margins fall to compensate for the lower risk. This is why grocery stores have low profit margins (low risk; groceries are recession-proof) while real estate has higher profit margins (moderate risk) and tech startups have even higher profit margins (and high risk). Reduced risk attracts investors and builders to a market which, through increased competition, reduces profit margins.

Specific policy reforms here are well-tread and, in some cases, already underway: reducing permitting wait times (because time adds uncertainty and costs money), improving inter-departmental communication (so bureaucrats can navigate bureaucracies), reforming design review (it’s not good at improving design and, again, takes a lot of time). But, what hasn’t been tried is going after risk directly: a plan to reduce the variance of outcomes in the permitting process.

Financial risk is measured in variance of returns and we can similarly measure risk associated with permitting offices and review boards by measuring the variance of outcomes — “approved” or “not approved,” to give a probably-too-simple metric.

The city can therefore reduce the financial risk of development by examining comparable projects to determine if and where outcomes differ, determine if the differences are justifiable and, should they not be, enact the specific reforms to reduce variance in outcomes. This is more of a heuristic than a specific policy. It guides us towards identifying the specific reforms and, consequently, can be generalized to apply across jurisdictions with diverse planning and development contexts.4

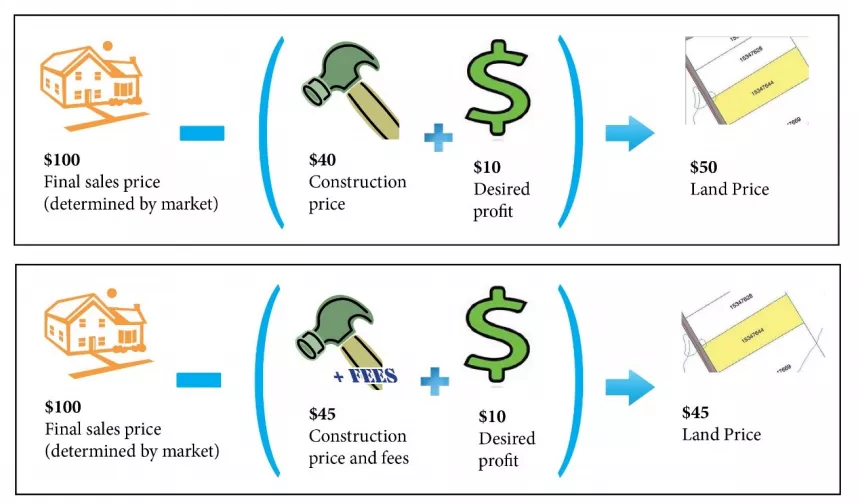

But making permitting outcomes clearer doesn’t directly help affordability because land owners can now sell their land for more. Market-rate housing prices are largely set by demand which is, at its most fundamental, a function of the number of people in a housing market times their average wages. When clearer permitting outcomes reduce developers’ profit margins, the cost of development goes down. This doesn’t reduce the price of housing, yet. The market price for land, on the other hand, is set by subtracting the cost of development from the market price of housing. In other words, it is the residual of the market price after everyone (except land owners) gets paid. When development costs go down, land prices go up. Conversely, when development costs go up, land prices go down as the diagram below shows.

Diagram from Policy Options Report on incentive zoning reform in Seattle. (Rick Jacobus and Joshua Abrams)

So how does reducing the variance in permitting outcomes help affordability? It doesn’t if we stop here. It just makes land owners richer when they sell their land. In order to help affordability there needs to be a way to capture the value permitting reform adds to land.

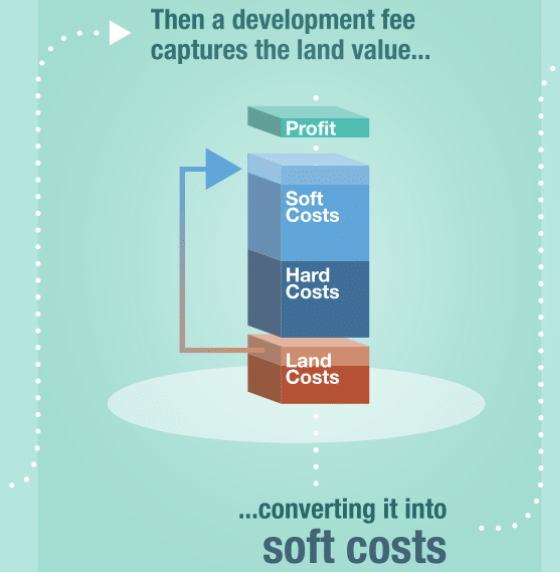

3. Capture land capital gains by charging a fee on development so that it scales with the value of the land. Then put those fees into non-profit housing development.

Because land price is set by the residual market price of housing after the cost of development is removed, if development fees go up then land prices go down. Next, in order to put the fees to use, the fees are directed to non-profit development which typically serves populations at 50% or 30% of the area median incomes. These groups, making less than $48,000 and $28,800 for a Seattle family of four, respectively, are not served by new development and unable to compete for older market-rate units. What are now capital gains on land would be captured and transferred into a distinct housing market that is presently under-served by the public sector and completely unserved by the private sector.

The more value we are able to add to land by reducing risk in the permitting process, the more value we can extract from land through the likes of inclusionary zoning and linkage fees. The 6,000 new affordable units expected from Seattle’s MHA recommendation would seem meager if we enact these first two programs together.

So much has been written about the supply side of housing even though demand primarily drives housing prices. Commentators and activists recognize that there’s nothing we can do to discourage large migrations of high-income people moving to an area and driving up costs, short of destroying urban livability. Opening up a garbage incinerator in South Lake Union would dramatically lower prices but no one seriously wants that so we are left debating supply-side policy — the give and take of upzones and linkage fees that is central the HALA plan. However, there is one thing our state legislators or the Supreme Court can do to change the demand side of housing — the fundamental cause of the affordability crisis in Seattle and many American cities.

4. Tax high incomes and put it into housing. Abide the Constitution and put it into education, too.

If we want to get serious about affordable housing we can work on implementing the first three recommendations above. But if we want to do something really significant we cannot ignore the demand side of the housing problem. The big problem of housing affordability — the one that has been considered too big to address — is that income inequality has been intensifying and this is especially true in cities like Seattle.

Part of this is driven by the increased size and speed of global capital (look for an international capital gains tax, like the one recommended in the penultimate chapter of Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century to fix that). But the fundamental component of housing demand is population times average wages and it’s by taxing high-end wages where we can have the biggest impact on demand.

Seattle developers have been building for the higher end of the income spectrum for some time because that’s what high land prices force them to do. I’ve already outlined a plan to lower land prices through development fees above but we can also reduce the demand that drives high-end housing construction that is resource intensive and takes up precious space from more modest housing.

State voters failed to support a high-end income tax in 2010 but with anxiety over housing costs having ballooned since then, a high-wage income tax sold as blunting the effects of high-wage earners on housing prices has a new and timely appeal. The passage of a small tax on high-wage earners in Seattle earlier this year is evidence that politicians are willing to take a risk on something that seemed impossible not too long ago. The Washington State Supreme Court will decide the constitutionality of that law but in the meantime we should begin the coalition building for a larger income tax by emphasizing the connection between an income tax and stunted rents.

A 10% tax beginning at 150% area median income ($100,800 for a single person) would make a significant dent in the distortionary effects the expanding income gap has on the housing market. 10% brings us in line with income tax rates in Oregon (9%) and California (11%). For higher incomes we can have higher tax rates. Let the bean counters figure out the specifics because the evidence says high-end income taxes are indeed a free lunch. Studies on high-end income taxes have shown that wealthy people do not pack up and move when their income taxes go up. And by not taxing high-end incomes we are — in an expression borrowed from developers — leaving money on the table.

In the meantime, as we wait for a lengthy legal battle to play out, concentrating land value, taxing land value, and building affordable housing is economically, legally, and politically viable. It can be implemented long before the Supreme Court rules on an income tax.

With the new revenue from a high-wage income tax, the state can choose to invest directly in affordable housing or, maybe, fund the services — schools, utilities, transit, etc. — that an additional 2,000 or more units per year will bring to Seattle.

Finally, a progressive income tax, the most politically (and legally) ambitious of these four proposals, diminishes the boom-and-bust real estate cycle. The funds from these four policies can be used as a kind of Keynesian counterbalance — saving construction industry jobs from the wild swings of the market that send thousands locally to the unemployment lines in bad times and inflate building costs during booms5. The larger the funds the stronger the counterbalance.

With the implementation of this final prescription we will have touched all the major components of housing price:

- We’ve increased land value by concentrating regional development potential in our jurisdiction through upzones

- We’ve decreased profits by reforming procedures and policies that create unnecessary differences in development outcomes, putting more value into land.

- We’ve converted all this concentrated land value into soft costs through development fees like inclusionary zoning or linkage fees.

- We’ve spent those development fees and a significant portion of the income tax during downturns in the market to counterbalance the boom-bust cycle that put about 30,000 area construction workers out of work this last go-around. Now, with scarce workers and scarce equipment, we’re paying for it with inflationary hard costs.

It’s now up to voters to demand local candidates pursue an affordable housing platform that works together to maximize affordable housing and it’s up to politicians to answer that call.

1. This is a gross simplification but it allows us a place to start talking about the limits of inclusionary zoning as a policy.

2. There are a few ways to approximate the wealth concentrated in land. Using a generic allocation approach, I take the 1:4 ratio of land to improvement value of new houses (the commercial ratio is less regular with downtown projects up to 1:8 but less extreme for lower-risk projects outside the core) to come up with a back-of-the-napkin estimate. For example, a new townhouse in a close-in neighborhood sells for $1,000,000 and, with a 1:4 ratio, $200,000 comes from the land. Then, taking the annual value of new building permits in Seattle ($2.63 billion per Localscape property new building permits in last 12 months in Seattle on 8/25/17) and dividing by 4 ($657 million) gets us the value of land under new buildings. If we can capture 50% of that value (a rate similar to a land levy in Bogotá, Columbia known as the Betterment Levy) and get 1-for-1 matching funds (from local and federal funding sources) then you get about 2,200 new units of affordable housing per year or, in HALA terms, 22,000 units in 10 years without increasing the cost of private sector development. And that’s a conservative estimate because it doesn’t take into account the other set of policy recommendations above that first seek to increase the value of urban land before capturing it.

3. Telecommuting, the one technology with the promise to dramatically decrease the cost of transportation like rail and elevators did more than 100 years ago, never fully materialized.

4. Which isn’t to say that popular reforms like fixing design review or eliminating inspection redundancies aren’t valuable. These are often idiosyncratic to a jurisdiction and don’t generalize easily to different places. In any case, these fixes, too, add value to the land which can be later captured to socialize the benefits of the reforms instead of privatizing them into the pockets of land owners.

5. More than a third of the area construction jobs using Bureau of Labor Statistics Standard Occupation Classification code 47-0000 (construction and extraction occupations) from May 2008 to May 2012 for the Seattle-Bellevue-Everett metro division.

Linkage Fees are a supply-side solution: Or, how land owners end up paying for development fees

Michael Goldman

Michael works as a real estate valuation analyst. He graduated from the University of Washington with a Masters in Urban Planning and a specialization in real estate. Before Serial broke the long-form true crime scene wide open, he had a podcast about pet adoption.