In June, I wrote about how the One Center City stakeholder group was heading toward a downtown where the Downtown Seattle Transit Tunnel could no longer accommodate buses, but where no additional street space had been allocated on the surface for public transit.

A quick recap: in either March or September of 2019, Convention Place Station is slated to close and the entirety of the tunnel will no longer be able to accommodate buses. Sound Transit and King County Metro are moving forward with truncating several bus routes that currently operate on surface streets in downtown Seattle or in the tunnel, particularly the routes that use the 520 floating bridge.

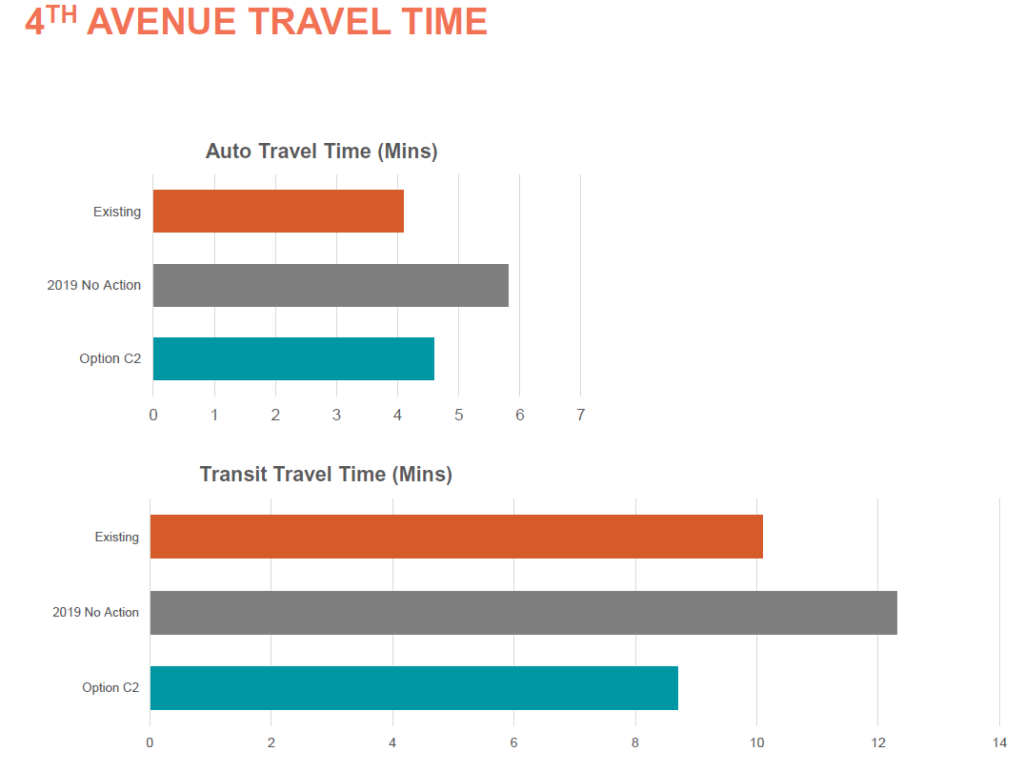

The idea of either adding an additional bus lane to 4th Avenue or even converting 5th Avenue into a two-way transit mall were both discarded as either impacting traffic too much for marginal gains in transit travel time (4th Avenue) or impractical to implement given the timeline and neighborhood opposition in the core of the downtown retail district (5th Avenue).

The major geometric issue to solve is northbound transit capacity. A crucial part of the plan is a two-way protected bike lane to galvanize the center city bike network and finally provide safe connections through downtown up the hill from 2nd Avenue. Traffic studies had shown that transit times would be slowed down if the number of buses on 4th Avenue remained the same and an additional general purpose lane was converted to a bike lane and the dedicated turn signals needed to keep users on the bike lane safe prevented free left turns off 4th.

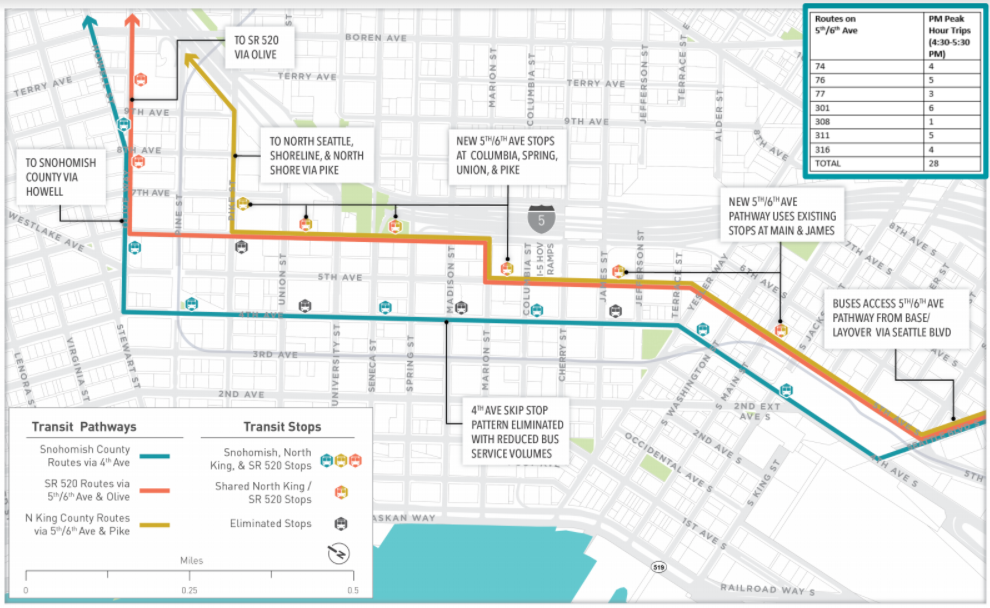

On Thursday night, the One Center City advisory group was presented with a solution. 5th Avenue, which is southbound for most traffic, has a continuous contraflow transit-only lane that currently ends at the express lane entrances to I-5 at Cherry Street. If this was extended to Marion St, and a transit only lane installed there, buses could get onto the new two-way 6th Avenue, which has room for an additional transit lane. From there buses have an easier way to get out of downtown via Pike Street or Olive Way. Just under 30 buses per hour would use this pathway during the PM peak when traffic is at its worst.

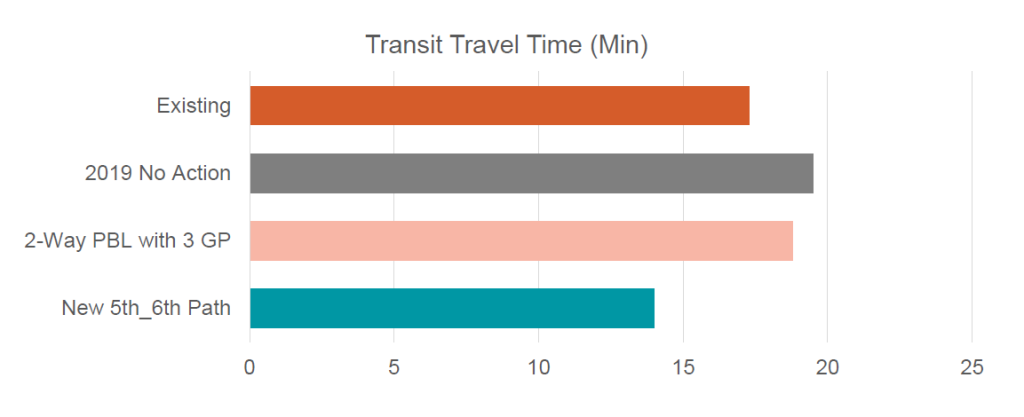

Buses that use this route would have a quicker travel time through downtown than with any other option, including current travel times and travel times on 4th Avenue with the single transit lane remaining.

In addition, because those buses are removed from 4th Avenue, travel times on that street increase for the remaining buses, which can now move more freely and do not have to leapfrog each other. In addition, the signals along 4th Ave are proposed to be adjusted so that right-turning traffic has a dedicated signal allowing vehicles to exit the transit lane without waiting for pedestrians to cross the street, keeping buses moving. Travel times for private automobiles on 4th Avenue will increase only slightly due to one lane’s repurposing as a bike lane.

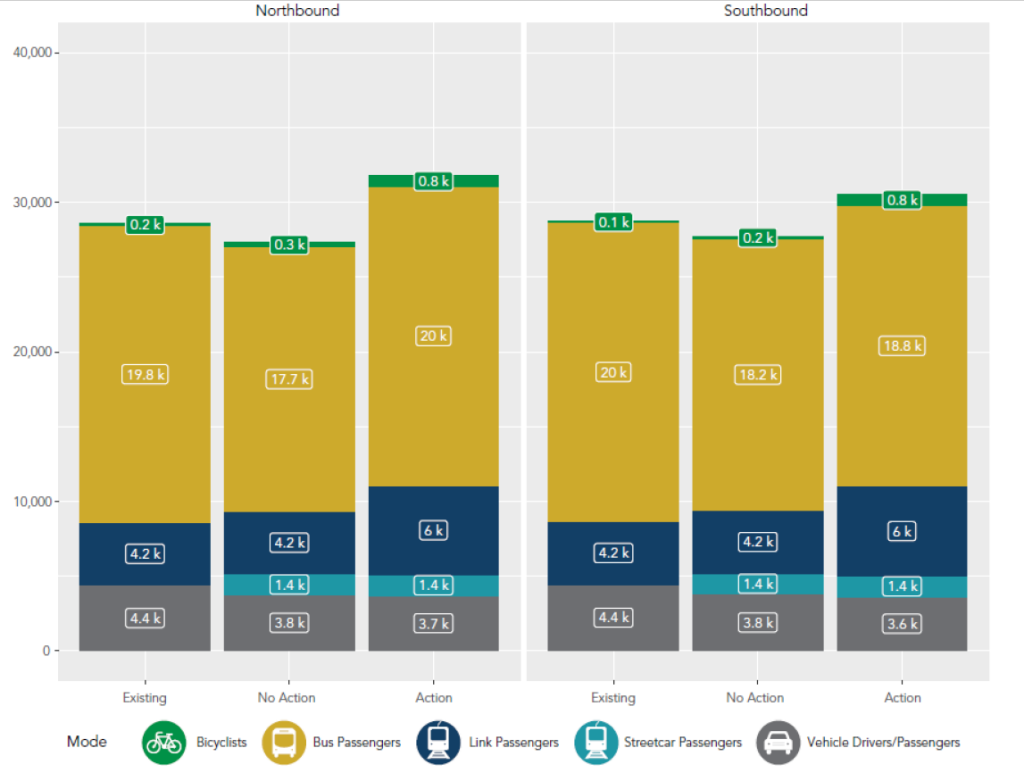

The proposed changes are going to increase overall user throughput on these streets downtown, as shown in a graphic presented to the advisory board. It illustrates pretty well the benefits that come from prioritizing transit northbound, where Link is not as able to get people to their destinations. The only problem with the graphic? There’s an entire mode missing: pedestrians. The throughput of people on foot downtown is not something that should be discounted when viewing capacity issues like this, but gains for pedestrians in One Center City are more elusive, and I plan to address them in an upcoming article.

Growing Bicycle Mode Share in the Center City

With the addition of another north-south bike route through downtown, and the long-awaited installation of protected bike lanes on Pike and Pine allowing easier bike travel between Capitol Hill and Downtown, as well as the installation of other facilities on 7th, 8th, and 9th Avenues, the One Center City bike improvements are expected to take what are currently estimated at 42,500 daily bike trips in all Center City neighborhoods (including Uptown, Capitol Hill, and South Lake Union) to 110,000 daily bike trips in 2023. That projection includes 25,000 daily trips made on bike share bikes by then, under the assumption that the free-floating bike share model currently in pilot sticks is still operating then.

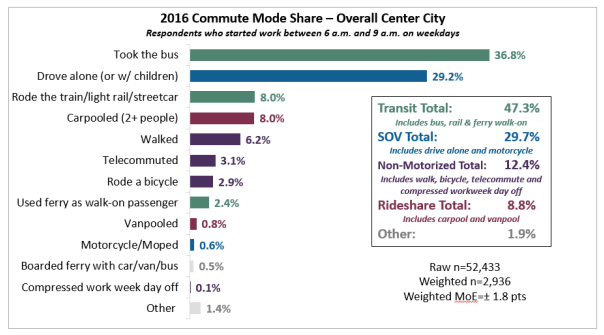

The number of people who commute into the center city by bike has been stagnating for the past few years, with the 2016 number holding at 2.9%. With the number of center city jobs estimated at 250,000, this suggests that just over a third of the bike trips in the center city right now are commute trips.

The Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) is moving quickly to implement the core components of the next stages of the downtown bike network, with crews out this past weekend putting down the first markings for what will be the protected bike lane on Pike Street between 2nd and 6th Avenues. SDOT intends to have those east-west PBLs completed this month, and to have the first segment of the 4th Avenue PBL in place in central downtown by the end of this year. It’s almost as if a galvanizing event that determines the future of the city is happening in early November.

begin of pbl layout on Pike pic.twitter.com/3P3I2ckcl9

— Dongho Chang (@dongho_chang) September 16, 2017

3rd Ave Restrictions to Expand

In addition to expanding off-board payment to all buses on 3rd Avenue, which has been part of the One Center City plan for a few months, the transit agencies are responding to calls for more priority on the existing 3rd Avenue transit street by recommending two changes: that the restrictions that do not allow private vehicles to travel more than one block on the street be extended from peak hours to the entire day (not 24 hours, but from the current morning period through the evening period), and extending the geographic range for those restrictions north from Stewart Street where it currently ends to the very important Belltown transit hub of 3rd & Virginia.

Many advocates are correct to lament the lack of compliance and dearth of enforcement along the corridor as a good reason not to expand this imperfect system. Ironically, it can seem traffic actually moves faster when vehicles do not adhere to the restrictions and simply travel along the corridor with buses. Drivers exiting 3rd Avenue in front of waiting buses encourages conflicts with pedestrians. 3rd and Pike Street was ranked the third most dangerous intersection for collisions over the past 10 years, which is insane given how few vehicles we should be seeing turning off a transit-oriented street. Ideally the political will would exist to turn 3rd Avenue into a true transit mall, but it’s pretty clear that we aren’t there yet.

The map below shows all of the proposed changes for 3rd Avenue through 6th Avenue.

Moving Forward with One Center City

The advancing of a new transit pathway through downtown is a huge achievement for the agencies involved in One Center City. Now that the pure geometric questions of how to prioritize transit and implement the center city bike network through downtown have clear answers, the agencies, with the help of the advisory group, can move on to the important issues of public realm improvements in the near and short term.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.