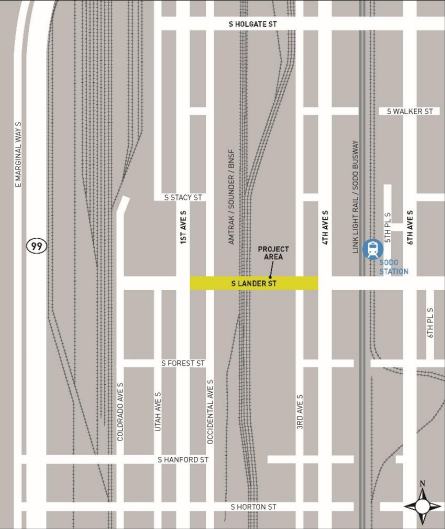

On Monday the Seattle City Council passed a resolution signaling intent to move forward with plans to renovate the Seattle Center Coliseum (popularly dubbed KeyArena despite shirked royalties by KeyBank). The day after, the Port of Seattle came up with the additional $10 million to close the funding gap for the Lander Street overpass and the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) announced it would begin construction as soon as next year.

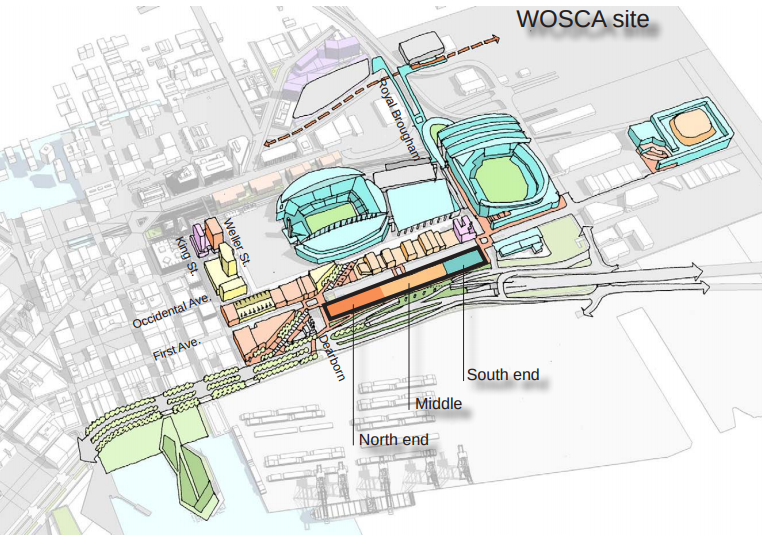

Seemingly, these moves close the saga of where Seattle would put the arena to host its WNBA team, the Seattle Storm, and perhaps lure an NHL or NBA expansion team. The arena will be the existing Seattle Center Coliseum renovated to the demands of the modern NBA and NHL (read: lots of luxury box seating) as proposed by the last bid standing from Oak View Group. To fill the $564 million complex, CEO Tim Leiweke said the group will not just lure an NHL team and (eventually) bring back the Sonics but also attract enough concerts to make it a “top ten venue.”

SoDo Arena Prospects Dimming

Although Oak View Group’s arena deal isn’t quite a done deal yet, its progress seems to be slowly closing the door on a SoDo arena. The move to solve Lander Street Overpass’s funding gap without the help of the SoDo arena deal takes away one of lead investor Chris Hansen’s major public benefits and points of leverage. Last year, the Seattle City Council denied Hansen’s Occidental Avenue vacation proposal, and he came with a sweetened offer, withdrawing the request for $200 million in municipal bonds and adding $10 million in Lander Street Overpass funding for the street vacation. The council took a wait-and-see approach.

Now, the City says the SoDo street vacation is on indefinite hold as it negotiates the final Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with Oak View Group regarding the Seattle Center proposal. City officials expect a draft MOU by September 12 and hope for a final agreement by the end of the year, Geoff Baker reported. Hanson has an active MOU himself, but it will expire in December if he doesn’t secure an NBA or NHL team within that time. Securing a team within four months seems a tall order.

Hansen doesn’t seem to be giving up just yet; his group commissioned a study allegedly showing the SoDo Arena would be a better deal for the City. The study was authored by Dr. Justin Marlowe, a professor of public finance at the University of Washington’s Evans School of Public Policy and Governance. Marlowe’s model indicated the SoDo Arena would funnel three times as much money into the City’s general fund, but it does not appear the study took into consideration the financial losses the City would be likely to sustain once SoDo Arena makes the publicly-owned (and currently profitable) Seattle Center Coliseum obsolete. The arena’s Paul Thiry-designed roof was officially deemed a historic landmark this month; thus, if the City wanted to redevelop the Seattle Center site as anything other than an arena, its options would be very limited. Perhaps the City would profit from a SoDo arena magically appearing on its tax rolls, but how much more than it would lose as the Seattle Center Coliseum falls in disrepair and disuse?

Lander Street Overpass: Political Football

Ryan Packer argued the City was ranking the Lander Street overpass too high of a priority given its big price tag (now estimated at $125 million) and other more pressing transportation priorities to fund–priorities that better serve people walking and biking. We now know that includes a court order to build 1,250 curb ramps per year until it has fully complied with the Americans with Disabilities Act. The 22,500 total curb ramps mandated could cost upwards of $300 million unless SDOT significantly trims its costs per installation. Not all of Lander’s funding is fungible–$45 million comes from a federal grant for example–but $20 million comes from the Move Seattle levy, which was billed as a multimodal package, and conceivably could have been transferred to other projects approved in the levy.

Now, to be fair, the overpass will include two curb cuts and some accommodation for pedestrians and cyclists on one side of the street, as the project website describes: “The new bridge will feature a 14-foot walking/biking path on the north side of the bridge that is physically separated from the road. The bridge approaches will also include new curb ramps that meet current standards for accessibility.” Kudos, SDOT. Just 22,498 curb cuts to go. And maybe that south side sidewalk one day.

Proponents of the SoDo Arena were quick to point out Lander Street Overpass blocks Occidental Avenue three blocks south of where the Port of Seattle has argued Hansen’s blocking the same avenue with his one-block street vacation would gravely jeopardize freight mobility. While on face value this is a bit ironic, in reality Port of Seattle’s freight mobility concerns appear to have more to do with the additional traffic the arena would generate on other freight routes rather than on Occidental Avenue itself.

By investing an additional $10 million to close the Lander Street Overpass funding gap, the Port of Seattle kills two birds with one stone. The extra money clears the last hurdle for the overpass it has deemed essential for the reliability of both freight rail and trucking. Plus, the move also holds off the SoDo arena development it sees as worsening traffic and encroaching on industrial lands east of its freight terminal. How long the Port’s move holds redevelopment at bay is another matter.

What Happens To SoDo?

SoDo arena backers have argued if Hansen’s bid is blocked he could still redevelop the large site–even under existing zoning–as 85-foot tall office towers, and they seem to suggest this would be a worse outcome for the Port of Seattle. SoDo Arena’s Lead Landscape Architect Mark Brands argued as much in a project update video in May.

“What happens if the city council rejects the updated street vacation request? The answer relates to the rapid pace of growth in Seattle and the likelihood the site will be redeveloped as office buildings, which current zoning allows for,” Brands said. “Unlike having an arena on the site which will generate traffic at non-peak hours in the evenings and weekends, traffic to and from the office building will be in direct conflict with the freight community.”

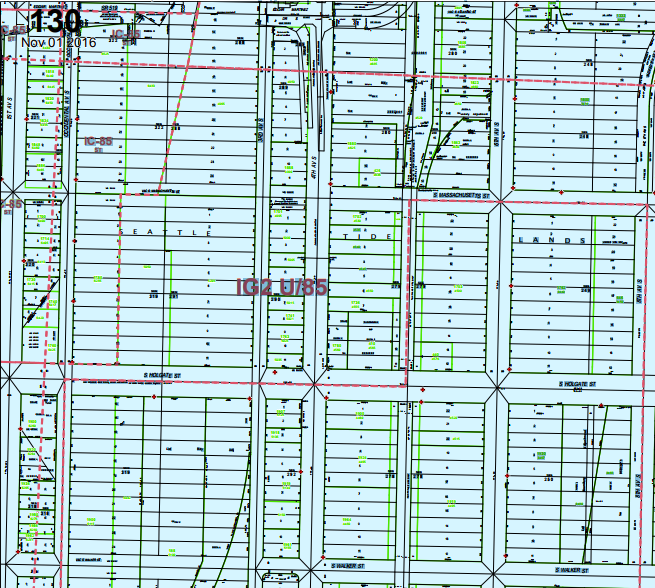

While Brands is correct current zoning allows office development, he may be overselling how attractive it would be considering existing code stipulates the offices must be small due to skimpy maximum use sizes for offices in industrial zones (i.e. IC-85, IG-1, and IG-2.) Small office buildings are not likely to be very profitable projects, especially given the high price Hansen paid for his SoDo land–his group paid close to $125 million for the 12.65 acres it has accumulated, Chris Daniels reported.

That said, an overhaul of the Stadium District zoning and development standards has long been in the making. A 2012 Stadium District Concept Plan by the stadium authorities that oversee Safeco Field and Century Link Field envisioned building 2,000 homes within 15 minutes of the stadiums, in addition to adding hotels, a promenade, and even a waterfront streetcar (following First Avenue as far south as Starbucks Center). The Department of Planning and Development (DPD) did a soberer assessment and issued a Stadium Study in November 2013. Fatefully that was the same month Mayor Mike McGinn lost his re-election bid; the city council shelved the plan. Under Mayor Murray, the City undertook an industrial lands survey to get a better sense of whether it was adequately planning for future industrial needs. Concluding that process may provide a path to enacting the Stadium District plan.

Chris Hansen’s group owns land within the Stadium District Overlay–which terminates at S Holgate St at its southern edge–but some of its purchases lie outside the overlay, placing those parcels within the Duwamish Manufacturing/Industrial Center (MIC). The City is under pressure to preserve lands for industrial use, particularly within the Duwamish MIC. Thus, it’s possible Hansen will get caught being a major industrial landlord when he didn’t intend to be. If a Stadium District rezone does happen (and let’s hope it does since building 2000 homes in the Stadium District is a worthy goal) then the Stadium District lands Hansen owns could be well positioned to redevelop.

What Happens To Uptown?

Meanwhile, it’s been an eventful time for the Seattle Center and the Uptown neighborhood that encompasses it. Not only will it upgrade its coliseum to a shiny new arena, the Seattle Center also appears to be getting a high school with its own (smaller) stadium. Moreover, Uptown is expected to get its upzone next month to unlock the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program, bringing both taller buildings and more guaranteed affordable homes to the neighborhood.

Detractors suggest developing Uptown with a bigger arena, a high school, and more housing will worsen already bad traffic and strain already strained parking. Which brings me to my last point: Uptown will also have its own underground light rail station by 2035 offering warp speed transit to Ballard, Downtown and anywhere else connected to Link. Additionally, Uptown could have another rail station if we dust off the Monorail taxing authority to upgrade the RapidRide E to an elevated rubber-tired metro. Transit is the future.

The featured image is a rendering of the “Arena in Seattle Center” by Oak View Group.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.