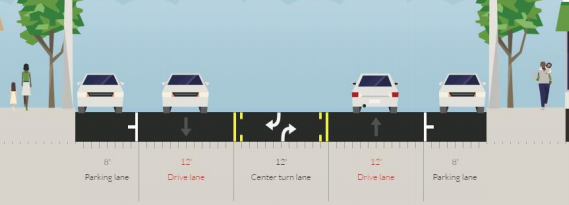

In August of 2015, a pilot project to tame a short segment of Seattle’s most dangerous street, Rainier Avenue, resulted in pretty dramatic results. When the street in Columbia City was reduced from two lanes in each direction to one, with an added center turn lane, collisions overall decreased 15% and those that resulted in an injury were down 30%. Crashes involving pedestrians and people on bikes were down 40% and only one person involved in a crash in the study area since the pilot project was implemented has been seriously injured.

The number of drivers speeding has also come down quite dramatically while overall travel times for drivers on Rainier through Columbia City are only slightly up. A pretty significant amount of traffic on Rainier Avenue has been diverted to Martin Luther King Jr Way, a street that is still under capacity for vehicle traffic based on its overall design. The first phase of the Rainier “road diet” (a term I eschew as it usually results in more roadway for other users) was by all accounts a resounding success.

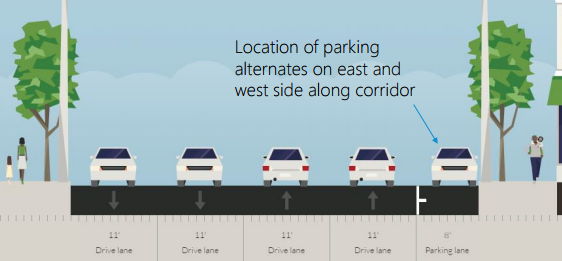

The long-term future of Rainier Avenue looks even better than a simple four-to-three lane rechannelization; changes planned for the busiest part of Rainier, in Mount Baker, will have repercussions for the entire street over the next decade. But in the mean time, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) is looking to expand the rechannelization further south, from S Kenny St where they left off in 2015, down to S Henderson St in Rainier Beach. Again we have a street with two lanes in both directions, where speeds are too fast and collisions much too common.

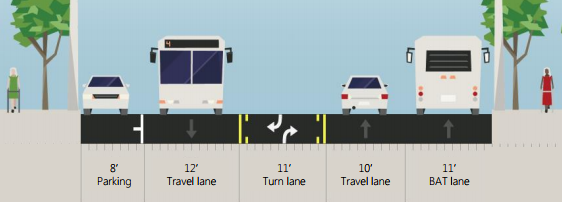

The most likely near-term improvement for the southern part of the street looks pretty similar to what was done in Columbia City, with one key change: there is room to implement a BAT (business access and transit) lane to give buses priority. A BAT lane was only installed in one segment on the Columbia City segment, at the intersection of S Edmonds St in the heart of the business district. I’ll talk more about the possible transit lanes in a minute, but for now the important thing to note is that a large travel lane that will be frequently empty, particularly at night, will clearly encourage people to both pass slower moving vehicles and also encourage higher speeds in general, if there are no visual cues to drivers that they should go slower. Of course, this is also the case with the center turn lane, but the BAT lane would compound this. This would be a big danger to pedestrians crossing at unsignalized intersections along Rainier.

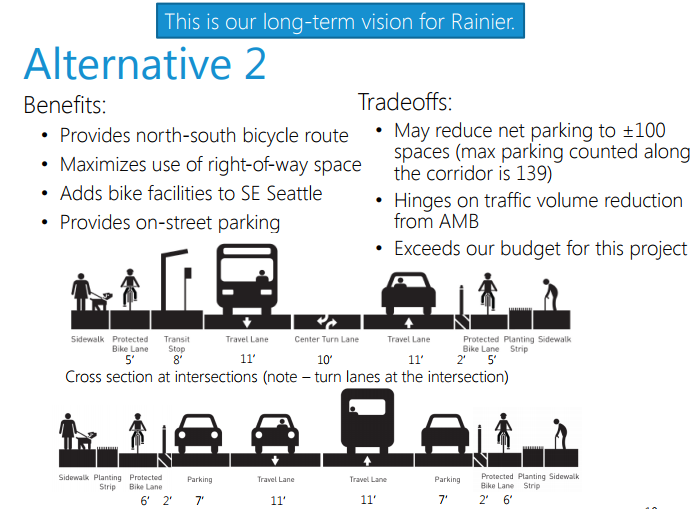

The second alternative is what SDOT is calling their “long-term vision for Rainier,” but they are noting up front that, even with an extra $1 million that was added to the budget last year for rechannelizing Rainier, that they don’t have the full funds to implement it.

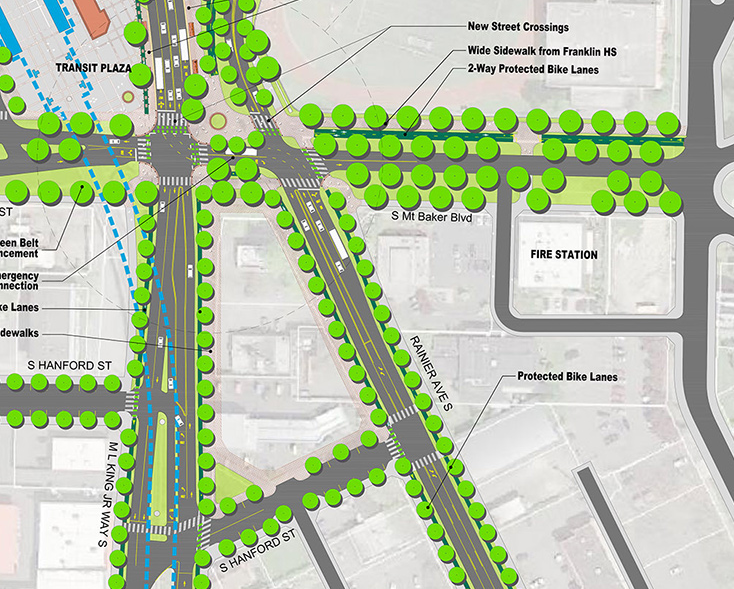

This proposal would add protected bike lanes on both sides of the street, reduce the street to two lanes in both directions, and at intersections bus boarding islands would be added, allowing buses on Rainier to stop in traffic and not waste time merging back into it. This is a successful model of transit operations as evidenced by streets like Dexter Ave N, but currently traffic volumes on Rainier Avenue are too high for this to be successful, according to the department.

The fact that SDOT considers bike lanes on Rainier Avenue itself to be the long-term goal for the street is a big win. It is only in the past few years that this reality has begun to be acknowledged broadly. There is no other flat route into and out of the Rainier Valley. SDOT is constructing a very long neighborhood greenway throughout the valley, but that will function as a compliment to, not a substitute for, a direct bike route to and from Downtown and other neighborhoods. But two things are clear right now: we don’t have the full money, and traffic volumes appear too high to implement the configuration that SDOT wants.

Accessible Mount Baker as the Catalyst

With the construction of Link light rail on Martin Luther King Jr Way S in the mid-2000s, a lot of traffic that had been using MLK switched to Rainier Ave. After light rail began service, the traffic stayed on Rainier Avenue. MLK is still under capacity, with some traffic that had been on Rainier returning to MLK with the first phase of the Rainier rechannelization in 2015. But the real catalyst for change on Rainier will be coming in the form of Accessible Mount Baker, a massive planning effort to make the transit hub where MLK and Rainier converge in Mount Baker less hostile to people on foot and bike.

Once complete, Accessible Mount Baker will function like a traffic diverter for Rainier Avenue, and SDOT expects the traffic volumes on Rainier to plummet. This will eliminate, according to the transit division at SDOT, the need for dedicated transit lanes in Rainier, even as Route 7 is upgraded to RapidRide status.

Accessible Mount Baker is not yet fully funded either, but is well on the way, and SDOT expects most of the improvements to be in place by 2021. Unfortunately, waiting for Accessible Mount Baker means waiting to see lower speed limits on the northern section of Rainier Avenue, where there are a lot of collisions due to high speeds.

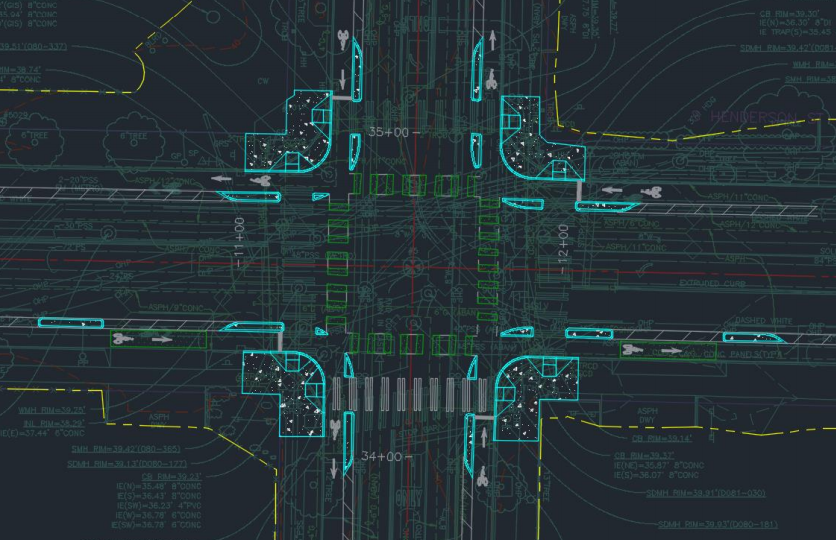

Henderson and Rainier

One of the most problematic intersections in the Rainier Valley is S Henderson St and Rainier Avenue. No other intersection in the Phase Two rechannelization project has had more pedestrian collisions. It was passed over by the Move Seattle Oversight Committee for improvements as part of the 2016 Neighborhood Street Fund projects, but it is being eyed again for special treatment as part of the Rainier Phase Two improvements, and it could be the first chance for Seattle to get a truly protected intersection. Unfortunately money is an issue here as well, with the current design estimated at over $1 million to implement.

An important thing to note is that while the proposed design certainly looks like it would benefit pedestrians and people on bikes, it isn’t quite a protected intersection because it is lacking the complete concrete wedges at all four corners, instead using partial concrete barriers that still leave riders exposed at certain points. We should not be reinventing the wheel every time when it comes to Vision Zero improvements like this, and we should find a way to get the cost down because, without improvements like this, we won’t make the required strides toward eliminating serious injuries.

Currently the Phase Two improvements are planned to be constructed next year. Rainier Avenue needs protected bike lanes now, but SDOT is laying out a clear path to getting there. The sooner we are able to get the entirety of Rainier Avenue changed, the better.

You can read more about the project alternatives and next steps at the SDOT project site.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.