Seattle Subway’s Vision Map generated a great deal of attention and that’s great for growing the transit-advocacy movement as we seek to build our success in passing ST3. That said, some neighborhoods were conspicuously missing from the vision, such as First Hill and Belltown. Generally, the principle in building high capacity transit should be start with your highest transit-use neighborhoods and then work your way out. Almost invariably the highest transit use neighborhoods are dense in housing, jobs, and/or entertainment. First Hill and Belltown are definitely in that category–the densest census tract in Washington state is in Belltown–we should definitely be including them in our rail plans. One way to do that would be upgrading the RapidRide E to elevated rail and then extending it to First Hill and potentially on to the Central District or Capitol Hill.

High Ridership

Jane Jacobs advised transit planners to look to their network’s busiest bus routes when deciding where to build rail. The RapidRide E fits the bill as Metro Transit highest ridership bus route, hitting 17,000 rides in 2016. (Highest ridership even without a N 38th St stop to serve Lower Fremont, the busiest neighborhood it crosses before reaching downtown.) The Aurora Avenue corridor carried 29,500 rides when Routes 5, 26, and 28 are included since they use it to and from downtown. For perspective, South Kirkland to Issaquah light rail is projected to get daily ridership of 12,000 to 15,000 in 2041, not even surpassing today’s RapidRide E.

Obstacles

Seattle Subway sites engineering challenges when explaining why Aurora Avenue wasn’t included in their plans. However, building elevated would seem to minimize many of those issues, such as tunneling under the Fremont Cut and avoiding the Bertha tunnel (by going over it rather than deep under it.) Building elevated rail rather than a subway on Aurora Avenue makes the problem more clearly political; we may have to take a lane away from general traffic to build the support structure for elevated rail and the associated stations. Sounds far-fetched. But what if Sound Transit did WSDOT a favor and purchased SR-99, or at least the center lanes, reducing their maintenance load? Controlling SR-99 right-of-way, Sound Transit would have the power to realize an elevated light rail plan. The pinch point would likely be the George Washington Bridge, which is aging and not necessarily light rail ready but perhaps could be reinforced and retrofitted. If not, perhaps we have to assess whether we’re approaching the time to plan a replacement for the bridge, which was dedicated in 1932.

The obstacle E rail still faces if it ventures toward First Hill is that old Seattle nemesis–a steep grade–and its newer nemesis: crossing I-5, but those challenges may not be so insurmountable. Compared to engineering deep tunnels and stations, smoothing out the grading of the elevated track toward Capitol Hill and First Hill doesn’t sound so bad. That routing would require gaining about 250 feet in half a mile. Making a 8% or 9% grade out of that is conceivable.

Bolder, please. pic.twitter.com/Y9dkeqk8og

— Qagggy! (@Qagggy) July 18, 2017

Another obstacle is overcoming aesthetic objections to elevated rail in dense urban areas. It’s clearly not out of the realm of possibility since Sound Transit prefers to use elevated rail in Ballard–although, side note: we may change their mind when the difficulties and expense of a second Salmon Bay bridge crossing become more apparent. People may associate elevated rail with the failed monorail expansion measures; however, when King County voters realize they can get more transit for their money, it may prove popular again.

Nice — But to be clear — that yellow line isn't on our map (yet anyways.)

It has some pretty serious technical challenges.

— Seattle Subway (@SeattleSubway) July 19, 2017

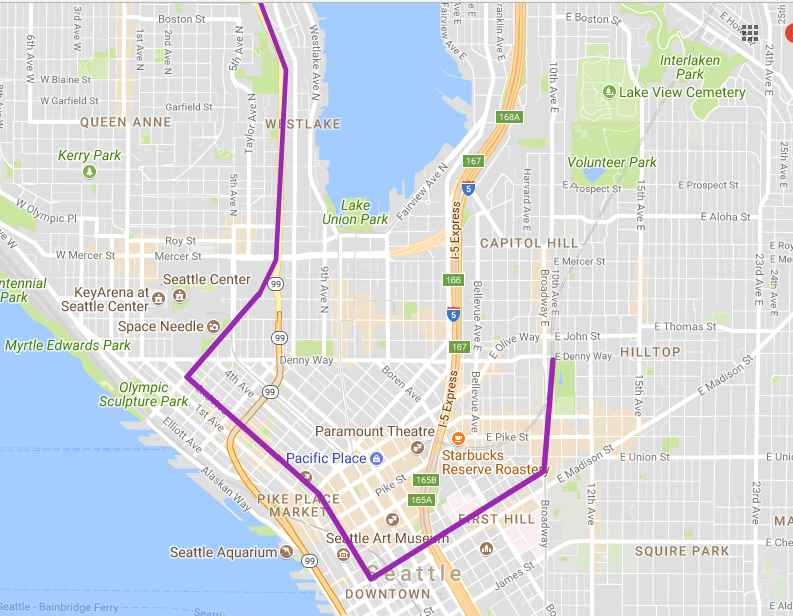

Despite the obstacles, we must get our priorities right; Seattle’s rapid transit network must work for our densest neighborhoods first before seeking out new car-dependent hinterlands to tame with transit-oriented development. Before we tackle another Lake Washington crossing and build two lines to distant Woodinville, we need to get our central Seattle neighborhoods integrated into the network. Building elevated rail on Broad Street, Way, Second Avenue, Spring Street and Broadway could accomplish that goal. The improvement in service would be enormous since downtown bus routes are often stuck in debilitating traffic at peak hours, even before One Center City attempts to manage controlled decline of downtown bus service rather than a visionary transit plan.

Serving The Central Area With Rail

Another benefit of this E alignment is it could interline with other lines like Seattle Subway’s Gold Line with service to the Central Area, or alternatively, the Gold Line would use elevated track to reach Downtown instead of tunneling up and around, shortening the distance of new tunnels to dig and track to lay. Instead of meandering up to Roy St and 15th Ave E, the elevated route could either take a direct line toward First Hill on Union or stop near Denny Way and Broadway to offer transfer to Central Link at Capitol Hill Station. An elevated Central Area line could potentially stop at Boren Ave and 16th Ave and 23rd Ave on E Cherry St before turning toward 23rd and Union or Mount Baker. That’s somewhat close stop spacing, but elevated stations are much cheaper than subway stations to build, opening up the possibility.

A Rail Plan For Seattle

With core downtown neighborhoods served and the eastern Capitol Hill, Central Area, Lower Fremont, Phinney Ridge, Greenwood, Aurora-Licton Springs, and Bitter Lake integrated into the rail transit network–in addition to the Ballard to Sand Point, Junction to White Center, and Ballard to Lake City lines already in Seattle Subway’s vision map–this ST4 package would have a lot to offer Seattle. Seattle Subway’s approach of focusing on King County may ultimately be the pragmatic path since the ST3 ballot measure had the most success there, while losing in Pierce County and breaking even in Snohomish County. Those counties may end up passing their own packages but scale of what’s needed is much larger in King County and rail is more clearly the solution for many King County corridors.

Seattle Subway helped ensure the ST3 ballot measure’s victory and their vision map will help inspire the grassroots movement to keep fighting for more transit in the Puget Sound region. A few improvements could help the vision map do even more to unite Seattle. To me the biggest improvement is turning the RapidRide E into an elevated rail line and extending it to First Hill.

Author’s Note: The earlier map created some confusion, so here is a map with a street grid for clarity. Alternate routes are possible, but this proposal centered on using Aurora Avenue right-of-way, until reaching the future (ST3) station at SR-99 and Harrison St, which will be underground and connect to Ballard.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.