My job as a dog walker and pet sitter takes me all over the city. I am car-free and rely mostly on transit, supplemented with car sharing. In recent years, Seattle has made good progress expanding its frequent service network and shifting from the old hub-and-spoke model to a frequent grid of routes. But for trips requiring transfers or without frequent service nearby, infrequent routes are a frustrating limiting factor.

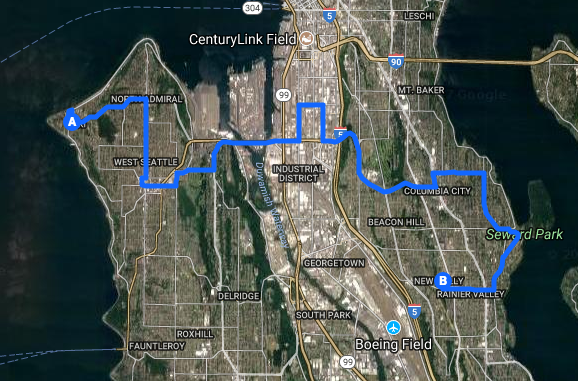

Route 7 works well enough with its 10-minute headways most of the day (dedicated lanes, signal priority, and ORCA readers, please!), but the advantages of that good frequency are largely lost when you have to wait 30 minutes to transfer to or from Route 50. At the same time, though it’s a low performer on ridership, the 50 is a useful route because it’s a crosstown line (doesn’t go downtown) that builds our grid so we can move away from hubs and spokes.

I rely on the off-peak 50 almost daily, and you needn’t look up its statistics to know that its ridership is low. It’s easy to see why: the route serves mostly low-density areas without many homes, jobs, or shops along the way. even much of the residential turf it serves is big, million-dollar houses with views of Lake Washington–these are generally higher-income people who are more likely to own cars and not ride the bus.

The right way to add frequency to the 50–and others like it–is to add height and density, trip origins and destinations, within its walkshed. One of urban planning’s most fundamental rules is that transportation and land use are inextricably linked, yet Seattle (like most U.S. cities) doesn’t coordinate these well. Planning and zoning by neighborhood is necessary, but why not also look at them by transit route?

There are pretty clear numeric thresholds showing how many trip origins and destinations you need along a route to justify a given level of frequency. The more development we focus along a route, the more it will rise in Metro’s metrics and earn promotions from 30-minute headways to 20 or even 15. That’s a virtuous cycle where marginal riders who won’t wait half an hour for the bus will start taking it. It also strengthens the frequent service grid, decentralizing transfers and adding crucial redundancy (choices and resilience) so people can circumvent, say, a Link disruption downtown and still get where they’re going with minimal delay.

I hear you objecting, “but those NIMBYs will never let us upzone!” Well, what if we add a carrot to the proposition? One of the reasons for my long-time support of inclusionary zoning is that it gives people concerned with affordability and displacement a reason to support increased height and density, as we see now with the University District, Downtown and South Lake Union, and Chinatown-International District. Likewise, if we could promise people that more density will bring their neighborhoods some of the benefits it should–like better transit–wouldn’t they be more likely to support such upzones?

This is what I call “The Density-Frequency Guarantee.”

It’s usually difficult to arrange in the U.S. because land use is controlled by city and county governments while transit decisions are made by separate transit agencies. And of course, King County Metro has to serve the whole county and allocate service based on its established guidelines and metrics. Metro can’t really make an explicit promise to one neighborhood to add service on its line if certain conditions are met. However, Seattle can through its Transportation Benefit District (funded through 2020 by Proposition 1).

Seattle and Metro could coordinate and set explicit benchmarks in residents, jobs, and local services for improving service to three (every 20 minutes) and four (every 15 minutes) buses an hour. Once the targets are met, the city could use Proposition 1 funds to buy service hours on these routes, fulfilling the promise of The Density-Frequency Guarantee. Infrequent crosstown routes get more frequency, and we get more homes and jobs located along them.

Jon Morgan is a former chair of the Seattle Pedestrian Advisory Board. He has been car-free since 1999 and lives in Rainier Valley.