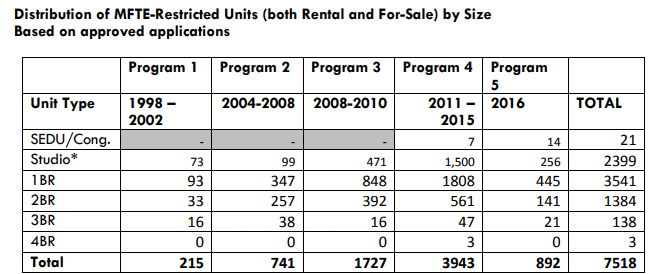

The Multifamily Tax Exemption (MFTE) program has approved 7,518 affordable units, as of the end of 2016. 855 affordable units were officially added to Seattle’s MFTE rolls in 2016, while one building with 12 affordable units saw its tax exemption expire along with the rent restriction. The 163 buildings actively participating have 28,580 total units and were worth $2.36 billion when originally appraised–and most likely have appreciated significantly since. Unfortunately for participating tenants, MFTE’s maximum rents jumped significantly in 2017, by as much as 6.9%. The recent rent hike only adds to concerns that the housing affordability MFTE is creating isn’t as deep as it should be given the scope of the tax breaks. Councilmember Lisa Herbold has argued the City of Seattle should be tracking the rent savings the MFTE program create versus the total tax break it doles out. It’s a complicated, perhaps oft-overlooked program but we will delve into the highlighted points below.

The MFTE program works by requiring new developments that opt in to provide 20% of their units to be affordable–some of those “family-sized”–in exchange for a property tax exemption, which they can use for up to 12 years by state law. Projects that do meet the family-sized units standard must provide 25% of their units as affordable.

Affordability is defined by unit type: the smaller the unit, the higher the affordability requirement, generally speaking. Most units are one-bedroom apartments that are set at 75% of Area Median Income (AMI) and were rented for $1,230 (or less) in 2016, followed up by studio apartments that rented for $903. If all utilities were included, the rents could be up to $125 higher.

The MFTE program was launched in 1998 and has gone through five different iterations. One consequential change was when the Seattle City Council voted in February 2015 to significantly lower the maximum rent for congregate microhousing and small efficiency dwelling units (SEDUs) from 65% (same as studios) to 40% of AMI (as a separate category). The chart above suggests SEDUs and congregate units almost never participate with the new rules. Before, some saw MFTE as a tax loophole for microhousing since the market-rate units were renting for close to 65% area median income at the time, even without the tax break.

Most of the buildings that applied for MFTE have continued participating, although some have withdrawn and a few have timed out of the program. The 2016 report states: “Since the program’s inception, the tax exemption has expired for 11 projects containing 451 total affordable units.” Below is how the program looked in 2015.

Table 1: 2015 MFTE Program Breakdown

| Unit Type | Area Median Income Cap | Maximum Rent | Maximum Income |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEDU/Congregate | 40% | $503 | $25,120 (1-person household) |

| Studio | 65% | $895 | $40,820 (1-person household) |

| 1 Bedroom | 75% | $1,219 | $53,775 (2-person household) |

| 2 Bedroom | 85% | $1,539 | $68,595 (3-person household) |

| 3 Bedroom | 90% | $1,827 | $80,640 (4-person household) |

Soaring Incomes Lead To MFTE Rent Jumps

One drawback of the MFTE program is that rents are capped at a ratio of Area Median Income. When median incomes go way up–like say when Amazon et al add a bunch of high-paying jobs–then the MFTE rates go up significantly. That happened this year as the rent limits for MFTE one-bedrooms jumped $85 to $1,315 (or $1,440 if utilities are included).

To tenants in the program, an $85 jump in monthly rent may feel like being at the whim of the market jump rather than protected by an affordability program. But such is life in Seattle where the median income has made enormous jumps, largely on the back of a huge wave of hiring at tech companies such as Amazon. Using Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) data for King County, the Seattle Office of Housing set $67,200 as the median income for a one-person household and $76,800 for a two-person household. Thus to qualify for a one-bedroom MFTE unit in 2017, a two-person household needed to have a joint income lower than $57,600; a one-person household would need to make $50,400 or less.

Table 2: King County Median Incomes & MFTE Rents

| Household size | 2015 Median Income | 2016 Median Income | 2017 Median Income |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-person | $62,800 | $63,300 | $67,200 |

| Two-person | $71,700 | $72,300 | $76,800 |

| Three-person | $80,700 | $81,300 | $86,400 |

| Four-person | $89,600 | $90,300 | $96,000 |

| 1BR MFTE Rent Limit | $1219 + utilities | $1230 + utilities | $1315 + utilities |

Seattle’s median income is lower than the King County-wide mark, but it seems to be growing even faster. Seattle’s median household income jumped almost $10,000 from 2014 to 2015 according to US Census data, Gene Balk reported. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) determined the median family income (four-person household) in King County went from from $90,300 in 2016 to $96,000 in 2017. That 6.3% year-to-year jump in King County median income explains how Seattle got a 6.9% jump in MFTE rents this year. But perhaps it doesn’t make it fair.

Councilmember Rob Johnson said he’d entertain the idea of tying MFTE’s rent increases to the Consumer Price Index (CPI) rather than floating with Area Median Income. Theoretically that would moderate rent increases.

“The chargeable rents are based on what can be afforded at various income levels that are based on Area Median Income and while it is frustrating to see those increase each year, I think from a policy perspective it is best to keep the affordability and rents tied to a measure that is compatible with other affordable housing programs,” Councilmember Johnson said. “One change that might be needed is to consider a CPI adjustment or other way to better tailor rent adjustments to our affordability goals.”

Fremont/Wallingford Example

Take the example of the Wallingford and Fremont neighborhoods. MFTE has delivered 223 affordable units in these two neighborhoods, according to the 2016 Seattle Office of Housing report. Nonetheless, new development is portrayed as “luxury condos” contributing nothing to affordable housing, which is misleading on several counts. First, development has been overwhelming skewed to apartments not condominiums in part due to strict condo laws in Washington state jacking up costs and liability concerns. Secondly, MFTE units are accessible to middle class households, and, as the data shows, their numbers are significant. Thirdly, new units prevent the worst kind of price escalation a booming economy and a capped housing supply causes. It’s easy to call new development “too expensive” but build no new housing and see how expensive existing housing gets. Price escalation has been severe in Seattle, but it could be so much worse. MFTE provides some relief from the high prices on the open market.

Table 3: MFTE Units In Fremont And Wallingford

| Building | Number of MFTE Units | Total Units |

|---|---|---|

| Bowman | 55 | 274 |

| Velo | 36 | 167 |

| Smith & Burns | 30 | 150 |

| Ray | 24 | 119 |

| The Noble | 19 | 93 |

| Positano | 14 | 66 |

| Vibe Fremont | 13 | 63 |

| All others | 32 | 154 |

| TOTAL | 223 | 1086 |

Does MFTE Deprive The General Fund?

The short answer is yes. Issuing a property tax exemption to hundreds of new buildings obviously affects the distribution of property taxes. Since city property taxes are levied at a set amount then distributed, this does not directly affect the total amount collected. However, Seattle Office of Housing (OH) calculates that it decreases revenues over the course of the programs in indirect ways–perhaps limiting how much property taxes can be increased for new priorities.

“Up until 2013 we thought that the cost of entire exemption was redistributed to other property taxpayers, now we know that about half (or about $85 million as of 2011) would be forgone tax revenue realized by the city over the course of all of those projects’ participation,” Councilmember Herbold said.

And MFTE will increase the burden on properties that aren’t exempted. Even so, King County calculates the shifted burden is relatively minimal. In 2016 it said: “Assuming a current median residence value of $480,000 and total real property value of $407.4 billion, based on the most recent 2016 figures as determined by the King County Department of Assessments, the MFTE program will result in an additional tax payment for the median Seattle homeowner of $10.84 in 2017, an amount that changes from year to year.”

The 2015 MFTE Report stated: “Assuming a median residence value of $427,000 and total real property value of $369.8 billion, based on the most recent 2015 figures as determined by the King County Department of Assessments, in 2016 the MFTE program will result in an additional tax payment for the median Seattle homeowner of $8.62.” And while the burden gets slightly heavier for other property taxpayers, Seattle OH estimated a pretty sizable chunk of revenue was lost in 2015. “Last year, they estimated, the city lost about $6.6 million in potential revenues to MFTE tax breaks, and shifted another $5.4 million from developers to the general taxpaying population,” Erica C. Barnett wrote in The C Is For Crank in February 2016

Councilmember Herbold laid out some issues with the program by email: “One question to ask is whether the cumulative rent savings for each of the unit types in a building is comparable to what the owner is receiving in the way of a property tax exemption. I have never seen this question sufficiently answered,” Councilmember Herbold said.

“[There are] confusing statements about the purpose of the program, which makes measurement of what we are getting for the tax exemption incentive very difficult,” she continued. “See this Auditor’s report: 2012 Audit. Is the goal 1. to buy down the rents in units of project development that is already occurring or is the goal 2. to stimulate development and buy down the rents in some of that development. Goal 1 would be very straightforward to measure. But goal 2 (which is one of the goals of the program) suggests that the tax exemption incentive should not just equal the value of the reduced rent, but it should also reward the developer for building.”

Other Means To The Same End

Another question Councilmember Herbold raised is whether another policy mechanism could get superior results. Would the same amount of money the tax exemption expends “result in more or less affordable units if we used some other taxpayer funded way to ‘buy-down’ the rents in private housing, for instance a City voucher program?” Councilmember Herbold asked.

If the City more carefully studied the question and found it could guarantee greater affordability with a voucher program using the lost property tax proceeds rather the existing program, that might be the way to go. To run some numbers, the estimated $12 million shifted or lost in 2015 would equal a $143 per month rent voucher for 7,000 households (assuming no overhead). If we were dealing strictly in lost revenue, the voucher would be about half that, based on OH estimates.

However, if policymakers strongly believe in stimulating multifamily development with incentives, then the existing MFTE program probably does that better. While rent vouchers would boost aggregate demand, developers would most likely prefer the easier calculation and more guaranteed benefit of 12 years without property taxes on their projected out budgets. Moreover, since the equivalent voucher would appear to be small, it seems like we are getting greater rent savings than the cost of the program, but it’s unfortunate this question has not been more explicitly tackled by the annual reports or occasional audits of the program.

Councilmember Johnson indicated he’d like to leave the program as is for now.

“At this point, the program is being used voluntarily by for-profit and non-profit builders to produce much needed affordable units in a very robust rental market,” Johnson said. “Therefore, I think that we should leave the balance of affordability and incentive in place.”

Moreover, he argued the latest update is making progress on its policy objectives, and that how the program is used could change as mandatory inclusionary zoning comes online.

“The program was updated in late 2015. Based on the 2016 data, it looks like we are having some success with the policy objectives of that update, for example producing more 2+ bedroom affordable units,” Councilmember Johnson said. “I think that it would be premature at this point to make additional changes. I am continuing to follow how the 2015 adjustments play out, as well as see how the program is impacted by the implementation of the Mandatory Housing Affordability program. I think we should take more time before evaluating what these programs are producing to make sure we are getting the most out of both programs and that they are still producing the range of unit mix and affordability that we need.”

Expiring Affordability

Altering the program to extend the affordability may get more urgent as a wave of units expire as they hit the 12-year limit for participation. Next year 35 units will expire, and 49 will expire in 2019 and 12 in 2020, but then the pace of expirations will pick up, Councilmember Herbold explained.

The affordability in MFTE buildings will be expiring over the next several years. There are a relatively small number (35, 49, and 12) of affordable units that would be lost due to exemption expiration between now and 2020. The number of affordable units lost due to expirations begins to increase significantly thereafter. This is due to the large number of projects and units that participated in the MFTE program in 2008. Larger losses of affordable units begin in 2021, with upwards of 3,000 affordable units expiring between 2021-2029.

Given the ongoing affordability crisis, Councilmember Herbold does see an opportunity to extend the life of affordability in the thousands of MFTE units set to expire in the 2020s.

“Now that the buildings are built, if we wanted to continue some sort of voucher program to maintain affordability in these buildings as the tax exemption expires, the question might be more straightforward about program goals, because we’d be rid of the question of a. whether we are paying developers to incent them to build and reduce rent or b. whether we are only paying them to keep the rents low,” Herbold said.

In an ideal world, 12 years might be enough time for new units to depreciate enough to be affordable to the middle class. Seattle probably isn’t living in that world right now, and a building hitting its MFTE expiration date could mean big jumps in rent for those benefiting from the restricted rents. On the bright side, people in MFTE units may already be used to $85 rent hikes so maybe it won’t seem so bad.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.