The Seattle City Council got its first glimpse this week at proposed rezones for three urban village nodes on 23rd Avenue in the Central District. On Tuesday, the Planning, Land Use, and Zoning Committee met to learn about the proposal from City staff and community members. While all three rezones are technically tied together, they are legislatively bifurcated into separate bills. The set of proposals are the result of the 23rd Avenue Action Plan which seeks to implement specific strategies to create walkable, mixed-use nodes that reflect the rich community character of the Central District, provide a variety of housing options, and support existing and new local businesses.

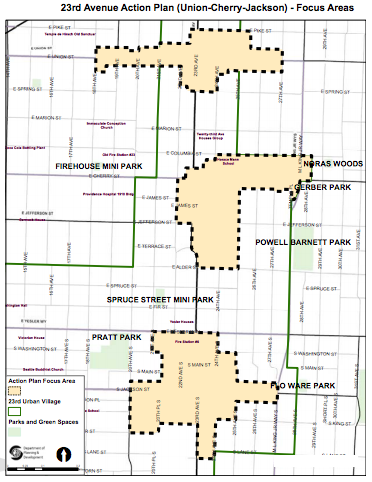

Each of the rezones would help implement the Mandatory Housing Affordability program by requiring most new development to contribute to the creation and preservation of affordable housing. The scope of the rezones is focused on urban village nodes located at Union Street, Cherry Street, and Jackson Street on 23rd Avenue, meaning that land use changes would only apply to a handful of blocks surrounding each key intersection. The three nodes are further broken down in to eight separate rezone subareas that are designed to achieve different objectives.

In March, the Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) published an urban design framework summarizing the overall vision and implementation strategies to improve urban design within each of the three nodes. Many of the implementation strategies are contained in the the rezone proposals as new development regulations (e.g., mid-block through connections, upper-floor stepbacks, and deeper ground floor setbacks).

Context and Displacement

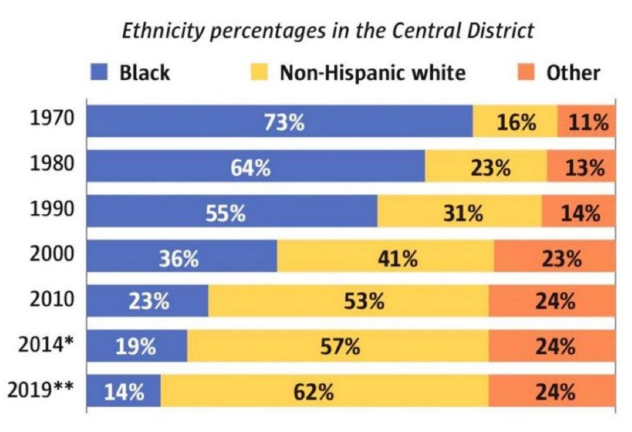

The Central District is recognized as a historically African-American neighborhood that has long been underserved and lacked a proportionate share of major investments. Part of that was the result of redlining through discriminatory lending and insurance practices that started in the 1930s, walling off whole neighborhoods in Seattle to African-Americans. The Central District was one place in the city that African-Americans could more easily locate in spite of these practices. From this context, the African-American community became deeply rooted in the neighborhood through institutions, businesses, and organizations. In recent decades though, the community has seen major cultural shifts as African-American residents have went from a majority to a minority in the neighborhood.

Gentrification has been a major contributor to the ethnic displacement that has taken hold in the neighborhood. African-Americans now make up less that 19% of the population. Some 47 years earlier, they made up 73% of the local population. A portion of this can be attributed to a net gain of residents in the neighborhood who come from other ethnic backgrounds. But there is an undeniable trend of African-Americans leaving while others–particularly Caucasians–move in. The 23rd Avenue Action Plan is one response to hold back this tide. The community plan is in many ways designed to retain an African-American identity and culture in the Central District.

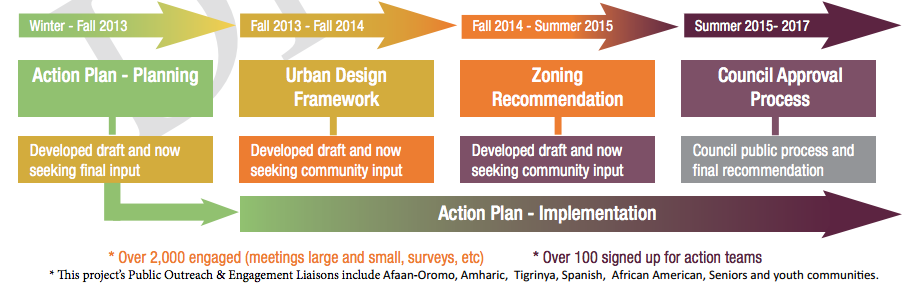

In fact, the 23rd Avenue Action Plan underpins much of the work related to the rezone and land use proposals being put forward. OPCD and other departments met with community action teams to develop an overarching plan establishing priorities, investments, tools, and strategies to be implemented in the years ahead. Examples include development of Jimi Hendrix Park and improvement to the Garfield Campus, a local commercial revitalization plan that focuses on African-American businesses, forthcoming commercial affordability strategies, affirmative marketing of subsidized housing to African-Americans, investments in new affordable housing projects, targeted use of Housing Levy dollars for homeownership and foreclosure prevention, and a variety of major transportation improvements like Madison BRT, Judkins Park Station, and 23rd Avenue Corridor Project.

The 23rd Avenue Action Plan has been a multi-year process that still has a ways to go, but could be adopted later this summer as a companion resolution to the rezones and land use changes. Instrumental in the process and development of the plan are groups like the 23rd Avenue Action Community Team and Central Area Collaborative, a diverse set of groups of individuals and businesses committed to building a strong community with unique identities.

Mandatory Housing Affordability

An important aspect of the rezones is the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) requirements that would be tied to them. Analysis by OPCD indicates that if all of the rezones are enacted at the planned 23rd Avenue nodes, approximately 50 new income- and rent-restricted units could be added in the next 10 years. City-wide rezones planned to follow would help realize even more affordable housing units in the area.

Developers would have a choice between building affordable housing or paying the City to create it instead. Payment is generally understood to help get deeper affordability and leverage other funding resources to realize additional affordable housing units that developers building on-site. City policy also places a preference to create affordable housing near the source of affordable housing payments, meaning that even if a developer doesn’t build affordable in the neighborhood, the City would likely still do so.

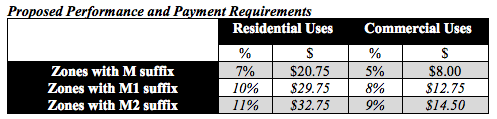

The MHA requirements differ based upon uses proposed for new development, whether a developer elects to build affordable housing and pay the City to do it, and the type of “M” suffix that is coupled with a property’s zoning. Residential development would have to provide somewhere between 7% and 10% of units as affordable or pay $20.75 to $29.75 per square foot as a fee to the City for affordable housing. Commercial development would have to provide between 5% and 8% of total floor area as affordable housing or pay a fee to the City for affordable housing equal to $8 to $14.50 per square foot. As an area with high displacement risk, the requirements are considered to be in the highest band applicable within the city.

23rd and Union

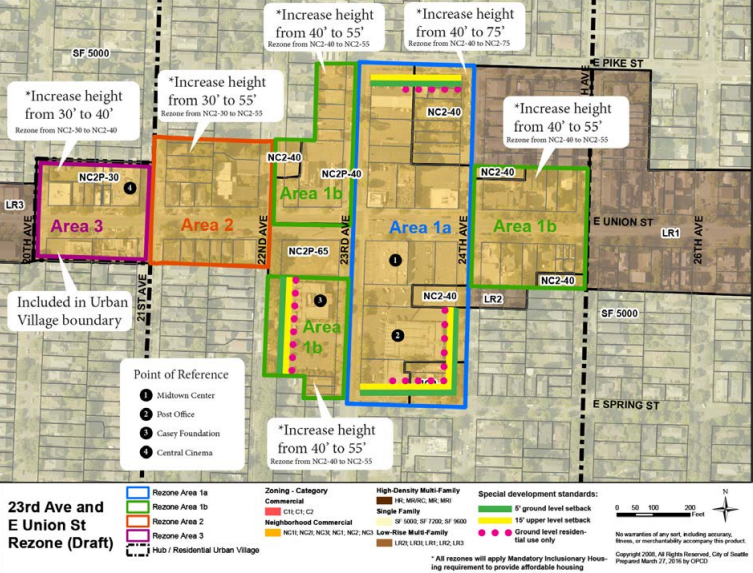

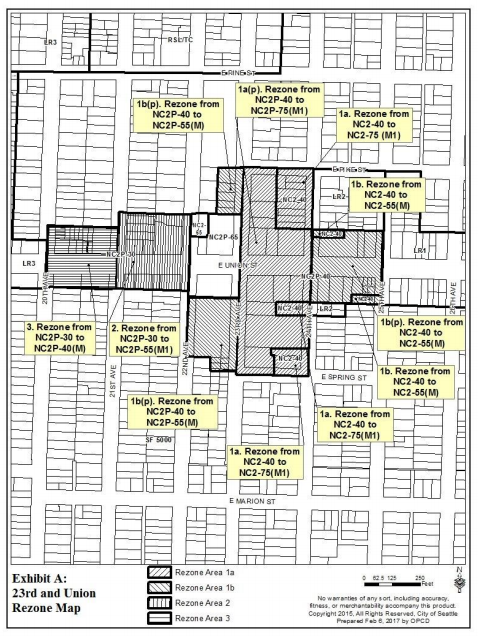

At the 23rd Avenue and Union Street node, OPCD has identified four distinct rezone areas. Zoning objectives differ between the areas, but zoning proposed for changes would all be Neighborhood Commercial 2 (NC2) zones that allow for both residential and commercial uses. Maximum building heights are proposed to increase by 10 to 35 feet. The highest building heights would cap out at 75 feet on blocks between 23rd Ave and 24th Ave. The lowest building heights would be at 40 feet. Lots adjacent to E Union St between 22nd Ave and 23rd Ave are not proposed for any changes. Additionally, some of the NC2 zones also would retain their Pedestrian Street designations (additional context on this is provided later).

The rezone proposal for 23rd and Union is coupled with specific urban design requirements. These would apply in Area 1a and Area 1b south of E Union St, as indicated in the map above.

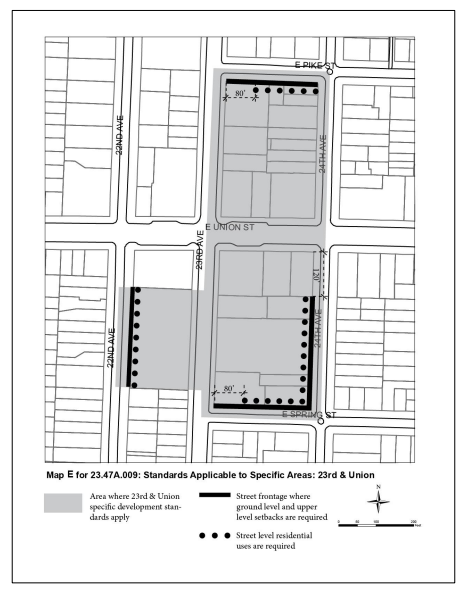

Street-level residential uses would specifically be required on the frontages of 22nd Ave, 24th Ave, E Pike St, and E Spring St, as indicated in the map below with black dots. The only exceptions to the residential use requirement are portions of the E Pike St and E Spring St frontages. The purpose of the requirement is to help better blend new development into the residential neighborhood areas near those block frontages.

Special ground floor setbacks and upper-level stepbacks would also apply to the same frontages as the street-level residential uses, as indicated by the thick black line in the map below. However, the requirements would apply to the whole block lengths on E Pike St and E Spring St, not just a portion. Generally, street-level setbacks would be five feet from the front property line. Upper-level stepbacks would apply to all portions of structures greater than 35 feet in height. Certain architectural and amenity exceptions to these standards would be provided for features like decks, balconies, and eaves.

About a third of the zoning changes would be coupled with an M-suffix, which is the lowest MHA bump that a development-capacity-increase rezone can get. However, the other two-thirds of zoning changes would get an M1-suffix unleashing the mid-range MHA requirements (see the MHA requirements table above).

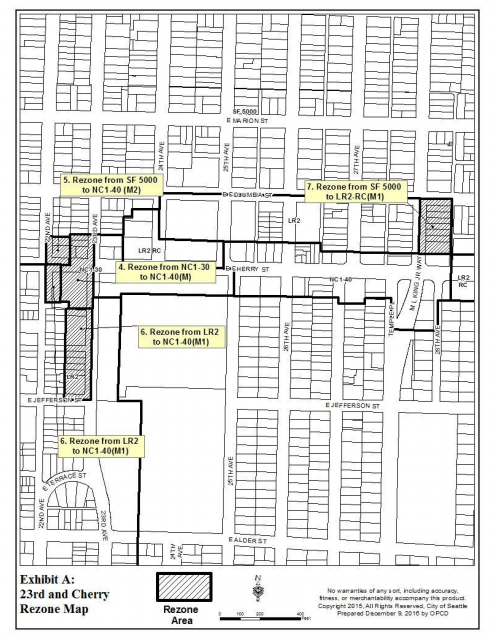

23rd and Cherry

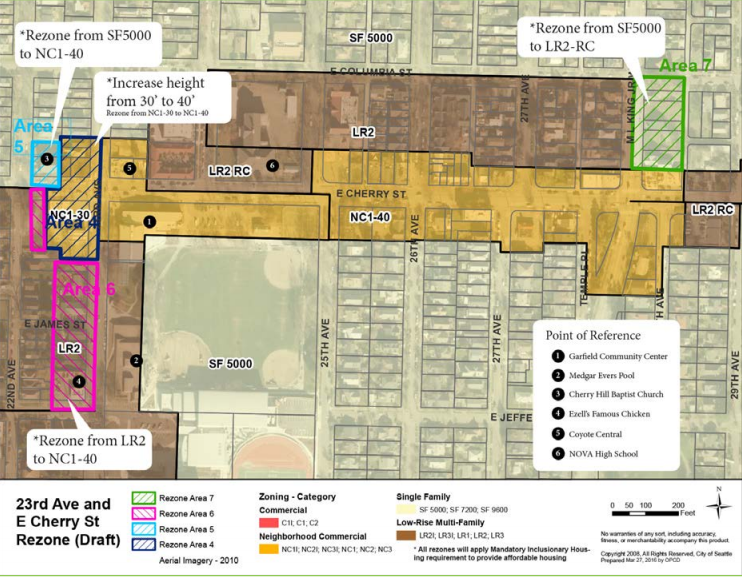

The 23rd and Cherry node has four distinct rezone areas that are proposed. Two of these would rezone single-family residential (SF 5000) properties to mixed-used zoning types: Neighborhood Commercial 1 (NC1-40) and Lowrise 2 (LR2-RC). The LR2-RC zoning would allow a limited amount of retail commercial uses as part of mixed-use development. Two pockets of Lowrise 2 zoning are also proposed to be rezoned to Neighborhood Commercial 1 (NC1-40). An existing Neighborhood Commercial 1 (NC1-30) would get a slight 10-foot height limit bump to max out at 40 feet like much of E Cherry St east of 25th Ave. In fact, all properties in the overall rezone proposal going to Neighborhood Commercial 1 would have a 40-foot height limit.

The rezones in the 23rd and Cherry node would unlock a mix of MHA requirements ranging from the low-end M-suffix to the high-end M2-suffix (see the MHA requirements table above).

The rezone ordinance for 23rd and Cherry would also come with some important changes to the Land Use Code. The changes primarily center on the MHA version of the Lowrise 2 (LR2) zone, but one key change also involves the MHA version of the Lowrise 1 (LR1) zone.

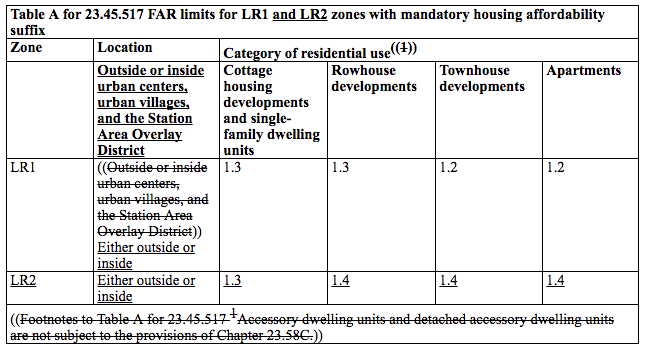

The first change would increase the floor area ratio (FAR) limits for different residential use types within an MHA LR2 zone. Generally, the designated use in the zone would get a 0.2 to 0.3 FAR bump from the base LR2 zoning variant (if you discount the green building incentive that comes with numerous requirements).

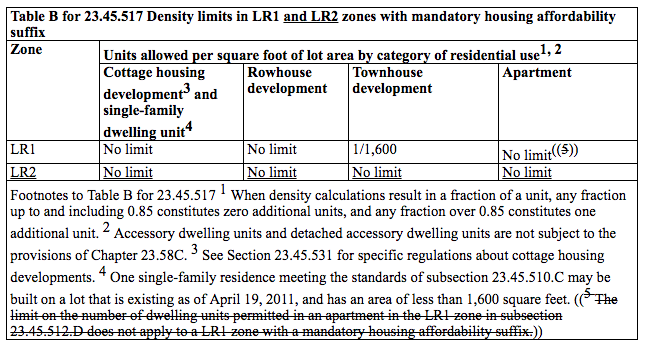

General density limits for residential uses in the MHA LR2 zone would also be established, though technically the development standard would clarify that there is not a restriction on density, in part because the FAR limit, maximum building height, and type of allowed uses would effectively create their own density limits. Compared to the base LR2 zone variant, the MHA LR2 zone would have more flexibility in density for all residential uses, except rowhouse development which already has no limit.

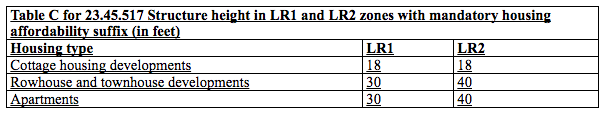

Lastly, the maximum building heights for uses in MHA LR1 and LR2 zones would be added. Cottage housing developments would be capped at 18 feet in height, which is already the current standard for both Lowrise zones. So the change in density limits and FAR are the main ways to achieve additional development, likely through wider structures. For rowhouse, townhouse, and apartment developments, the maximum building height in the MHA LR1 zone would be 30 feet which is the same for the base LR1 and LR2 zones today. However, it’s the MHA LR2 zone that would get a 10-foot height limit bump to a 40-foot maximum.

23rd and Jackson

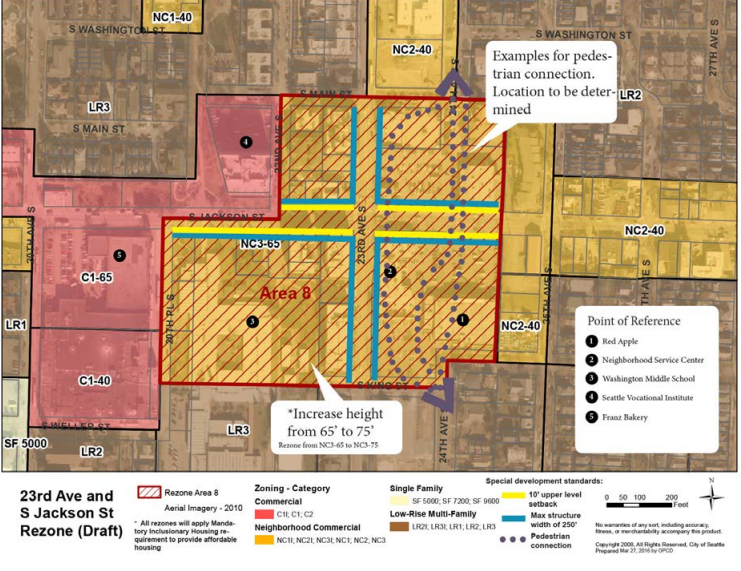

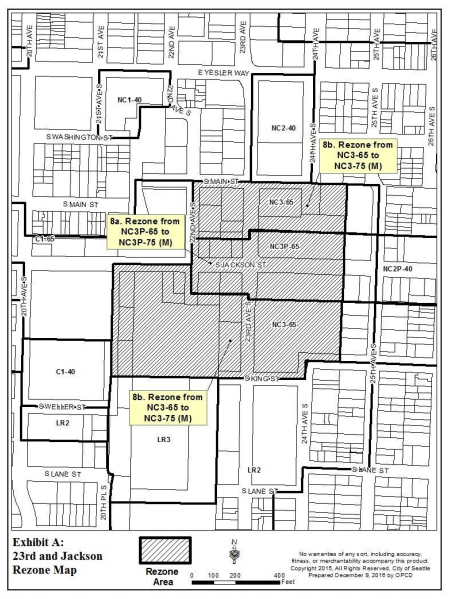

The 23rd and Jackson node has one general rezone area proposed. However, it is technically broken into three subareas since new S Jackson St is designated as a Pedestrian Street. Properties fronting S Jackson St, therefore, have a special prefix (the P-zone prefix) added to the underlying zoning designation–in this case Neighborhood Commercial 3 (NCP-65). Other Neighbhood Commercial 3 (NC-65) properties in the rezone area lack the P-zone prefix. The basic difference in the designation types is whether or not active ground floor uses and minimum development densities are required and where parking is allowed. All of the Neighborhood Commercial properties would get a 10-foot building height limit increase that maxes out at 75 feet (NC3-75 or NC3P-75).

Since development capacity would only modestly increase from the rezones, the lowest MHA requirements would be applied though the M-suffix (see the MHA requirements table above).

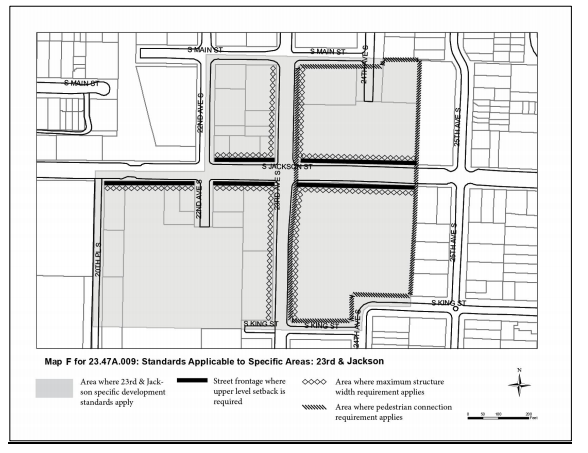

The 23rd and Jackson node would receive special urban design standards for development near the center of the urban village. The urban design standards focus on added stepbacks, maximum building widths, and a special pedestrian connection.

- Stepbacks. Buildings in certain areas would need to use upper-level stepbacks for portions above 45 feet on frontages identified with a thick black line in the map below. The upper-level stepbacks would need to be at least 10 feet from front property lines. Certain architectural exceptions to this standard would be provided for features like balconies and eaves.

- Maximum building widths. Frontages noted by the diamonds in the map below would be subject to a maximum building width of 250 feet. Buildings could be wider than this if they employ the use of facade modulation. The modulation would need to be at least recessed or projected 15 feet in depth from the rest of the facade and be at least 15 feet in width. Alternatively, buildings would need to be separated by at least 15 feet.

- Special pedestrian connection. For the large blocks between 23rd Ave S and 25th Ave S, a special north-south connection would be required for new development. The new pedestrian connection would need to be at least 15 feet wide and contain certain amenities, such as street furniture, bicycle parking, entries to businesses and buildings, overhead weather protection, or other pedestrian-oriented features. Additional requirements would also apply, including standards for the paved walkways at least six feet in width that connect to existing or planned sidewalks and crosswalks. The pedestrian connection could be located between buildings or between a parking area if fully separated with special treatments for pedestrian comfort and safety. Multiple developments would likely construct the pedestrian connection.

Next Steps

A public hearing on the rezones will be held Monday (June 26th) at Garfield High School. The meeting will kick off at 6pm. Over the coming months, Councilmembers will likely develop amendments and take up the overall package of legislation for a final vote sometime in August or September.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.