In late January, the four organizations involved in the One Center City plan–King County Metro, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT), Sound Transit, and the Downtown Seattle Association (DSA)–presented a set of options intended to alleviate the pressure on Downtown travel during what they are calling a “period of maximum constraint.”

To quickly recap how we got here: the expansion of light rail eventually will force buses out of the Downtown Seattle Transit Tunnel to facilitate higher train frequencies. The Washington State Convention Center (WSCC) wants to speed that time table up by as much as two years to as early as Fall 2018 to expand the convention center on the Convention Place Station site, which King County Executive Dow Constantine wants to sell for $161 million. The WSCC might not keep its mammoth $1.6 billion project on schedule and it might not gain approval until it convinces the City of Seattle the project’s public benefits are sufficient. Nonetheless, even without the added monkey wrench the WSCC Addition adds, light rail construction will require buses out of the tunnel before East Link is ready, leading to this period of maximum constraint and the need for One Center City.

However, the biggest culprit for the “maximum constraint” will be induced by the closure of the viaduct, which studies show will cause increased traffic on surface streets Downtown. Advocates urged city leaders to shy away from a single project meant to be a catch-all replacement for the highway, and to instead focus on improving Downtown streets and transit. That didn’t happen.

Last week, the One Center City advisory group got a look at what improvements are getting the green light, and which ones are going to be too disruptive, expensive, or take too long to implement.

Fifth Avenue Transit Mall Off The Table

The most ambitious idea to come out of the entire process was the concept of turning Fifth Avenue into a two-way transit-only street from Stewart to Jackson Streets during peak hours. This would have essentially reduced to zero the additional operating costs associated with increased congestion Downtown for buses, but also would have required up to $28 million in capital investments to reconfigure Fifth Avenue as a transit mall. It also would not have added very much travel time to personal vehicles Downtown, with the removal of bus lanes on Fourth Avenue and the conversion of Sixth Avenue to two-way operations between Stewart and Marion Streets. The Fifth Avenue transit mall was always going to be a stretch to implement in about a year to make the WSCC’s desired timeline and some leaders, including Councilmember Rob Johnson, had expressed skepticism that such a large investment was warranted when the period of utmost need would only last until 2023 when East Link opens.

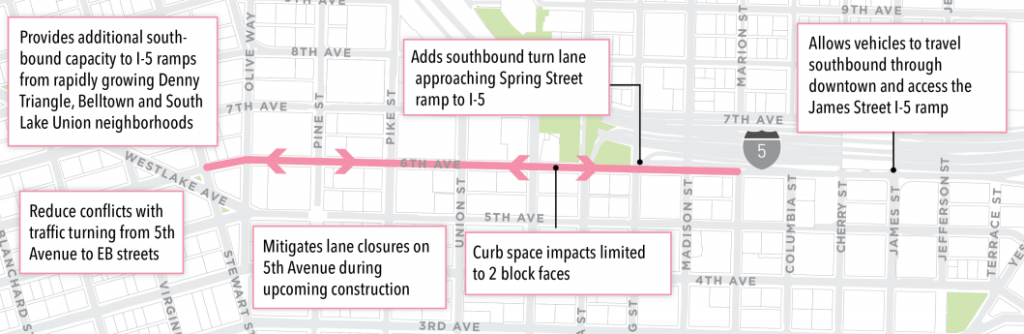

The recommendation for converting Sixth Avenue to a two-way street, however, is one that is moving forward. A two-way Sixth Avenue provides another way for auto traffic to get from North Downtown to I-5 apart from getting to Denny or Mercer Street. Funneling more cars through the central business district to get to I-5 seems to contradict with the goal of One Center City: to reduce the pressure in the CBD. Opening more avenues to induce demand in South Lake Union at the expense of central Downtown is something that should be viewed critically.

No New Transit Lanes Proposed in the Heart of Downtown

Apart from the Fifth Avenue transit mall idea, the other concept proposed in January was the addition of a bus-only lane to Fifth Avenue and an additional bus only lane to Fourth Avenue during peak hours. Two bus lanes on Fourth would allow high volumes of buses to pass each other when they do not share stops. This option is also not moving forward, likely due to opposition from multiple fronts. No other option would have removed as many parking and loading stalls (70 compared with 43 in the Fifth Ave transit mall proposal) and precluded any bike lanes from being installed on Fourth or Fifth Avenues due to lack of room. It also would have increased vehicle travel times outside of the bus lanes by the highest amount, by an average of 3.4 minutes southbound and 1.2 minutes northbound.

What does this leave? The only option that didn’t propose any new additional space for transit Downtown: the addition of operational enhancements to existing transit zones. Originally, this included all streets Downtown with transit on them: Second, Third, Fourth, and Fifth Avenues, but the latest plan includes no proposed changes for Fifth Avenue.

On Third Avenue, our (ostensibly) peak-period transit mall, off-board payment coupled with all-door boarding is proposed for all routes. This is long overdue and will improve the experience for all riders. It is not ultimately clear what the impacts that Metro might expect this to make to farebox recovery, but ultimately the operational gains should outweigh the loss of any fare revenue from increased evasion.

On Second and Fourth Avenue, the proposed changes would simply aim to reduce conflicts between buses and other vehicles at turns and intersections. These changes benefit both transit riders and those in personal vehicles. In addition, the improvements in dwell time on Third Avenue could actually mean that additional capacity is opened on Third and some bus routes could get moved there from Fourth and Second (which function as a couplet for many bus routes).

One thing is clear: if no additional lanes are to be added to Downtown to face this “period of maximum constraint,” then we must improve operations on Third Avenue by enforcing more stringent prohibitions on private vehicles and extending that transit-only restriction to all times of day, seven days a week. To invest in off-board payment and not make that improvement would be very short-sighted.

Bus Restructure Concepts Moving Forward

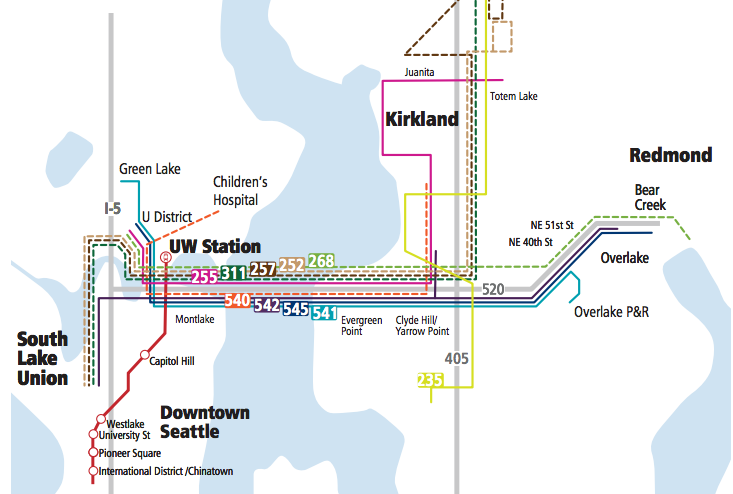

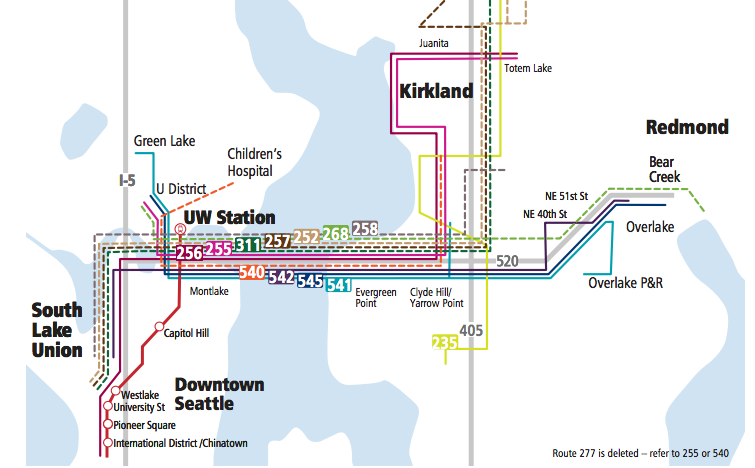

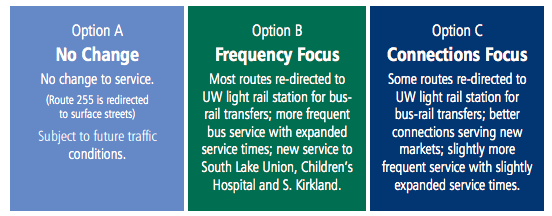

One major concept that is definitely moving forward is the truncation of several key routes at transit stations instead of bringing every trip Downtown. The most notable of these are the SR-520 bus routes: for example the 255 and the 545.

Metro is soliciting feedback on changes to all bus routes on SR-520. The two major options would both direct all buses that would be headed to Downtown Seattle to University of Washington Station instead. The only difference is that one would invest the extra service hours not spent going Downtown into fewer, more frequent routes, including direct Eastside service to South Lake Union, and the other would provide slightly less frequency and more connections. South Lake Union’s traffic negatively impacts bus reliability there as well. This begs the question: Would switching direct service from Downtown to South Lake Union really be more efficient?

Another way to ensure good connections as traffic worsens is to expedite Roosevelt RapidRide, which would provide dedicated lanes between Downtown and South Lake Union.

Metro is asking riders to take a survey on the different SR-520 options. All plans propose a substantial slate of improvements meant to make transferring at Husky Stadium better. It looks like this will include off-board payment and all door-boarding as well as improvements to bus stops and street crossings.

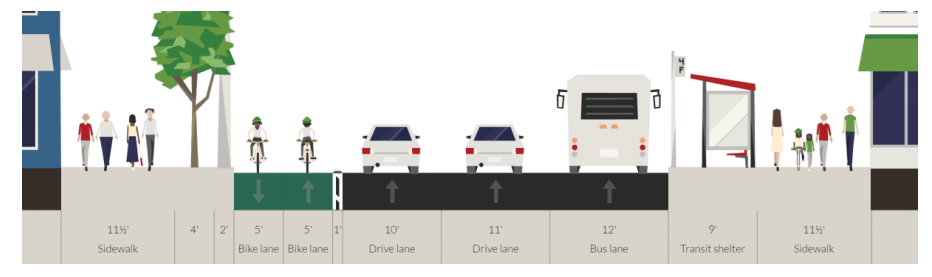

The bus restructure ideas moving forward also include: routing the 41, currently a tunnel bus, onto Pike and Union Streets and not running it through the entirety of Downtown. Stop improvements would be made at the bus stops on those streets to accommodate new riders.

In addition, most peak-only West Seattle buses would be routed to Pioneer Square Station and then to First Hill, rather than to the heart of Downtown. This would provide new service to the hospitals and remove 25 buses per hour from streets in the CBD.

Sound Transit Route 550 to Bellevue, however, is not proposed to have any changes. Originally, One Center City explored truncating the 550 at International District-Chinatown Station, but due to the removal of the express lanes on I-90 the agency determined that impacts to ridership would be too high to also consider forcing transfers.

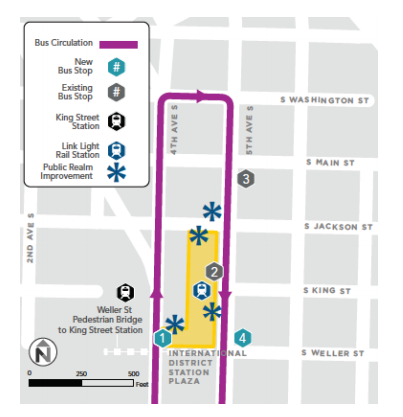

International District-Chinatown Station is slated to get some public realm improvements and bus stop reorganization. The old Waterfront Streetcar stop at 5th Ave S and S Jackson Stis finally slated for removal, improving the pedestrian experience around the station.

Protected Bike Lanes Moving Forward

One of the most hopeful items presented to the advisory group as a near-term recommendation is long-awaited progress toward a connected protected bike lane network throughout Downtown, including north-south routes east of Second Avenue and east west routes between Downtown and Capitol Hill. We appeared poised to make progress on the Basic Bike Network Downtown for which we and other bicycle advocates have clamored.

The plans call for protected bike lanes to be installed on Pike and Pine Streets between Second Avenue and Bellevue Avenue in 2018. Downtown these lanes would follow the direction of traffic, with eastbound bikes on Pike and westbound on Pine. This bidirectional couplet would continue even as users reach Capitol Hill, where those streets become two-way. Originally, this option proposed to convert Pike Pine to one-way operations on Capitol Hill also, but this has been taken off the table. This is good news, as converting to one-way streets would likely lead to higher traffic speeds unless extensive traffic calming mitigation was planned. (It wasn’t.) Luckily, that is not the direction that Pike Pine is headed.

The schedule plans to extend the bike lanes from Bellevue Ave to the existing lanes on Broadway by 2020, which is disappointing, but bridging a key connection that is missing around Boren Avenue and I-5 is essential to increasing bicycle ridership between Capitol Hill and Downtown. Currently Pine Street has painted bike lanes in both directions, so presumably riders heading uphill would be able to jog over to those from Pike Street to have some minor separation for two years.

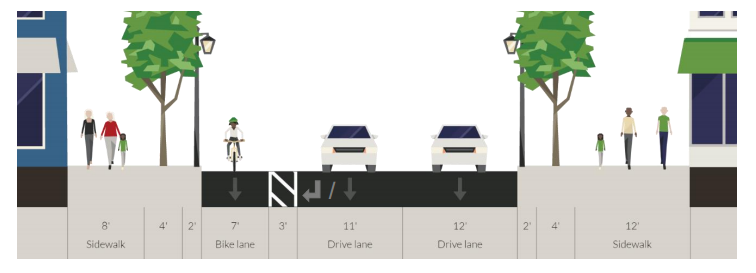

The north south bike routes in Downtown are still being determined. The choice comes down to a bidirectional facility on Fourth Avenue or a couplet, like on Pike and Pine, on Fourth and Fifth Avenues.

The other strategies moving forward are things that are good policy regardless of traffic impacts: focusing commute-trip reduction efforts on smaller businesses than mandated by state law, education about off-street parking facilities, and freight pilots like bike delivery and off-peak timing.

Taking Downtown Transit Could Lose Its Edge

The One Center City process has the potential to give Seattle an opportunity to jump-start improvements that could revolutionize Downtown travel, turning a crisis into a blessing. At this point, however, it looks like any transit improvements that could potentially negatively impact those who chose to drive Downtown are being taken off the table. Forcing bus riders to transfer to light rail is absolutely going to mean that some riders chose to drive or take company-provided shuttles.

We should move forward at full speed to prioritize boarding on Third Avenue, including further restrictions to private vehicles on that street. But ideas like an additional bus lane on Fifth Avenue should not be taken off the table. Record numbers of commuters are choosing to take transit over driving. Continuing this trend exactly when it is needed most is the most important outcome of One Center City and there is much more work to be done in that area. We have one final chance to improve transit and livability Downtown in advance of the viaduct’s demolition, and we need to take advantage of that right now.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.