Carolyn Mawbey is irked. The feisty 68-year-old former New Yorker gets around Seattle’s Uptown neighborhood mostly on foot but when the transportation department flipped a switch this spring, her Earth-friendly commute got considerably rougher. “At first, I thought there was something wrong with me. I used to get across the street in time and then the walk signals started switching to don’t walk before I could get across.”

It turns out the problem wasn’t the spring in Ms. Mawbey’s step. Quietly, right around April Fool’s Day, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) activated a new adaptive traffic signal system along the Mercer corridor. The system, according to SDOT, is intended to be a smarter approach to moving traffic.

While SDOT activated the system without fanfare, people who live and work along Mercer started noticing changes right away. Walk signals—previously switching from one phase to the next in a familiar rhythm—seemed to go haywire. Sometimes the walk phase would cut short, prompting people like Ms. Mawbey to sprint to the opposite curb (or suffer the wrath of turning cars). Sometimes the walk signal would appear, then time out, then suddenly turn to walk again, all while parallel vehicular traffic had a solid green. In the worst cases, the walk phase would be eliminated entirely for two or more cycles.

In the midst of this confusion, many pedestrians engaged in risky behavior, walking against the light and wading into traffic, or giving up and finding a different route. If Mercer were a suburban commercial strip, perhaps these changes would be considered just the latest indignity. However, the Mercer corridor cuts through the northern part of Seattle’s urban core, home to the Space Needle, Amazon, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and many of Seattle’s most prized commercial, cultural, and research institutions. The street life of this regional engine of creative activity and economic growth was being sacrificed in the name of getting cars to the interstate faster.

Adapting, but to whom?

It’s called an adaptive system because signal timing adapts to demand from users. Demand from cars is measured directly using inductive loops installed in the pavement. Demand from pedestrians, however, is less accurate. It depends on a person pushing a beg button, which some people do and some people don’t.

After observing risky behavior for more than a week, advocates recorded people trying to cross at the corner of 1st Ave N and Mercer. In the video below, at :08, a blind gentleman tries and luckily succeeds in navigating the crossing against the light.

Here is 35 seconds (6x speed) of people not getting a walk signal in an urban center and either sprinting or giving up. @dongho_chang pic.twitter.com/TCUOzzg5p3

— Queen Anne Greenways (@QAGreenways) April 10, 2017

The adaptive signal system had been in the works for several years. Sensors and other instruments were installed during the years-long Mercer Corridor Project but all those components, along with computer hardware and software, need to come together in a command center. So, SDOT built their system, officially dubbed SCOOT (for Split Cycle Offset Optimization Technique), in a piecemeal fashion as funding became available.

After millions of dollars, years of implementation, and several weeks of post-deployment observation, SDOT Director Scott Kubly held a press conference at the 37th floor of the Seattle Municipal Tower to unveil the system. Press coverage was uniformly glowing. The Seattle Times gushed “New, high-tech traffic signals make the Mercer Street trek less messy.”

Was the juice worth the squeeze?

The reality was not quite as rosy. The gains for cars were modest and the cost to safety and pedestrian mobility was high. Average travel time for cars moving in the westbound direction from one end of the corridor to the other, according to SDOT’s own figures, actually got worse. Eastbound travel times showed improvements of 18 seconds in the morning and 2.7 minutes in the evening. Meanwhile, people on foot were experiencing waits of more than three minutes just to cross the street. These small gains for cars were likely at the expense of people walking.

It’s worth noting that SDOT’s before-and-after evaluation didn’t include measures of pedestrian impacts. Were the needs of people walking even considered?

This signal gives 11 seconds to people walking and 55 seconds to cars. Even when there are no cars. @dongho_chang pic.twitter.com/5WvAyshKRy

— Queen Anne Greenways (@QAGreenways) May 24, 2017

Torches and pitchforks

By this time, neighbors were getting increasingly vocal. KIRO TV ran a feature story on April 27th highlighting the failings of the system but SDOT didn’t seem to be listening (except for City Traffic Engineer Dongho Chang, who took an interest and facilitated dialogue between concerned citizens and the SDOT signals team).

Pedestrians don’t like the signal timing on Mercer @seattledot. pic.twitter.com/mGGqfzI58U

— Queen Anne Greenways (@QAGreenways) April 28, 2017

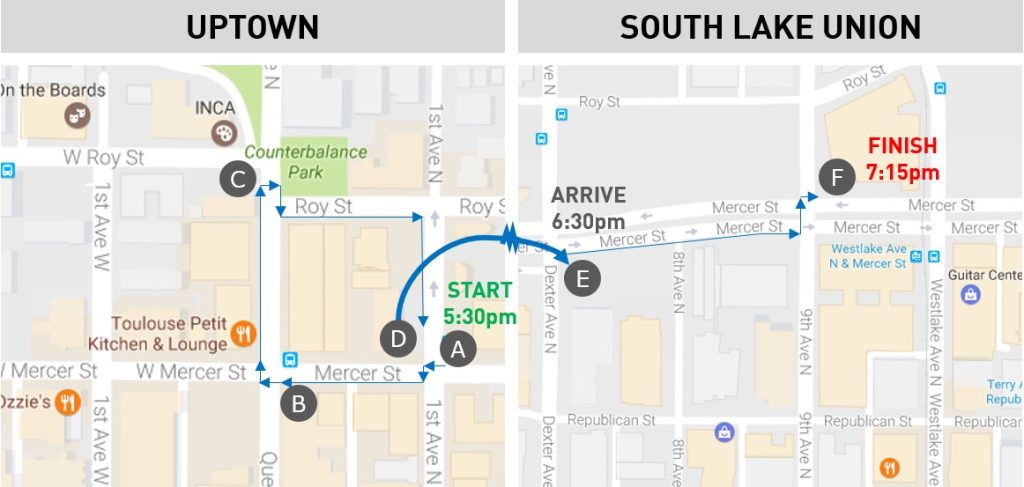

Improving walking and biking connections between Uptown and South Lake Union is a major priority for Seattle Neighborhood Greenways. So, on May 30th, Queen Anne Greenways, together with the Uptown Alliance and South Lake Union Greenways, organized a walking tour to highlight the problems on Mercer. Thirty-five participants—including SDOT representatives, members of the press, neighbors, and advocates—braved intermittent drizzle with a different volunteer leading discussion at each stop.

Right away, it was abundantly clear the new signals weren’t working for people on foot. When the group attempted to cross Mercer at 1st Ave N, the signal skipped several cycles and the large crowd waited for several minutes just to cross. This pattern was repeated at various stops along the way and it became clear that something needed to be done.

Takeaways

SDOT deserves credit for sending a high level delegation including Director Scott Kubly, Deputy Director Benjamin de la Peña, City Traffic Engineer and local legend Dongho Chang and Traffic Operations Manager John Marek. They listened, observed, and engaged in a lively exchange of ideas.

In the end, SDOT expressed a willingness to address the following items:

- Extend crossing time for pedestrians while parallel cars have a green light.

- Prevent signals from skipping the walk phase during any given cycle.

- Provide a protected left turn signal for west-to-south traffic at Queen Anne Ave & Mercer.

- Address the missing button at Roy St & 3rd Ave N.

- Re-evaluate average vehicular travel time to assess whether induced demand has erased previously measured improvements.

- Include pedestrian delay or other pedestrian service metrics in future evaluations.

Additional asks that didn’t get clear agreement from SDOT included the following actions to prioritize people walking and biking in Uptown and South Lake Union:

- Provide a walk signal without requiring actuation, particularly at Queen Anne Ave & Roy St and at Terry & Mercer, two crossings specifically designed to prioritize pedestrian mobility.

- Prioritize transit crossing Mercer in a north-south direction, particularly at Dexter Ave.

- Measure compliance with pedestrian actuation requirements and consider such data when requiring actuation.

- Include cyclist delay or other bicycle service metrics in future evaluations, particularly on routes crossing Mercer.

- Seek to more accurately incorporate pedestrian (not just vehicular) demand into their algorithms and ensure the system responds to it.

- Prioritize non-motorized modes.

- Address the issues with adaptive signals in the Mercer corridor before expanding use of the system.

What’s next?

Mercer represents the first SCOOT implementation in Seattle but it won’t be the last. Soon, SDOT hopes to roll out the system along Denny Way, a parallel corridor that cuts deeper into Seattle’s urban core, and more streets after that.

Meanwhile, Seattle’s mode-split goals may hang in the balance. Uptown resident Carolyn Mawbey might not be coaxed back into her car but others might. Will the system simply induce additional vehicular demand, erasing the modest gains in travel time observed in the first few weeks, while locking in the losses for pedestrians? Will Seattle drop more car-centric suburban traffic signal systems into the center city or will it direct scarce resources towards preparing for a denser future where walking, biking and transit access are prioritized? That remains to be seen.

Mark Ostrow (Guest Contributor)

Mark Ostrow serves on the Board of Seattle Neighborhood Greenways and is a core leader of Queen Anne Greenways. Mark is a principal at RK2 Advisory and a Trustee at Northwest Kidney Centers.