The Seattle Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) released the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the zoning changes its proposing in urban villages as well as commercial and multi-family residential areas outside of them across Seattle and which would implement the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program. Moving ahead with the EIS would clear a major hurdle on the path to greater affordability by increasing development capacity and implementing mandatory inclusionary zoning (a.k.a. MHA).

Three alternatives were studied:

- Change nothing;

- MHA rezones without a “displacement analysis;” and

- MHA rezones with a “displacement analysis.”

“The study isn’t presupposing an answer,” OPCD senior planner Geoff Wendlandt said in a phone interview. “Neither of these alternatives have to be the final alternative.”

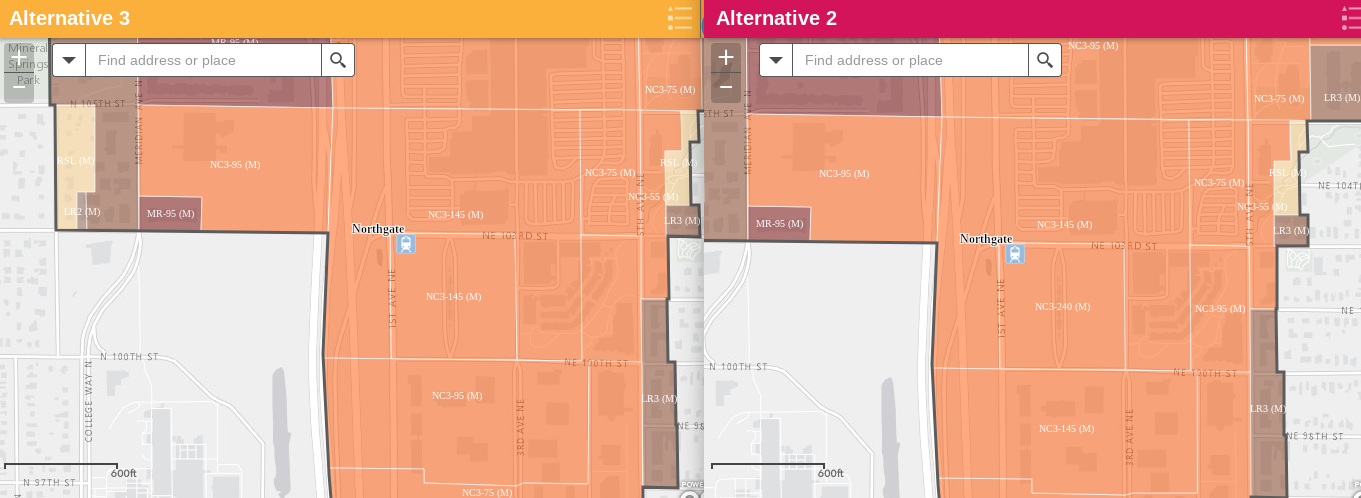

Wendlandt added that policymakers could pick and choose the best attributes of both alternatives, which appears to be the best course of action since each plan has its own strengths and weaknesses. Generally speaking, Alternative 2 seems to make best use of high-rise zoning, maximizing future station areas in Northgate and places along SR-522 BRT in Lake City. Meanwhile, Alternative 3 does a great job of maximizing mid-rise zoning in low displacement risk neighborhoods in North Seattle. Choosing the best features of Alternative 2 and 3 could result in an excellent land use plan. To peruse the Draft EIS zoning maps, click this link.

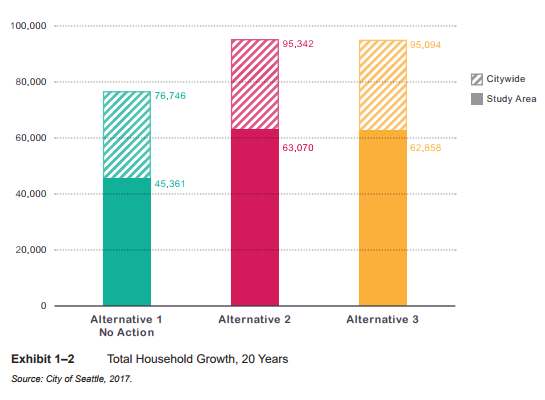

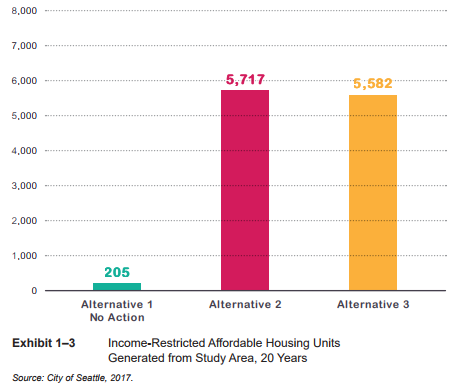

The summary suggests that Alternative 2 presents both the greatest capacity for growth and rent-restricted affordable units.

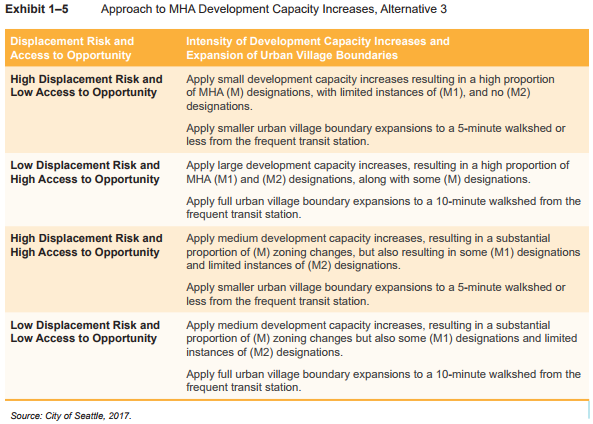

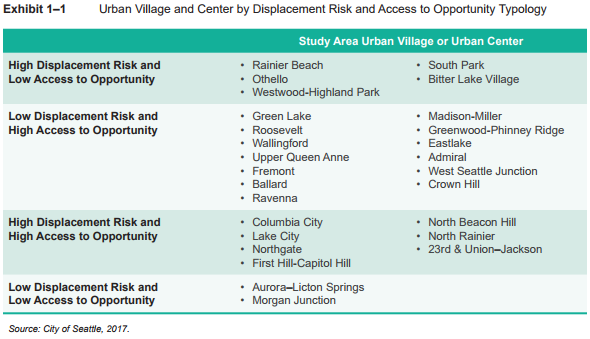

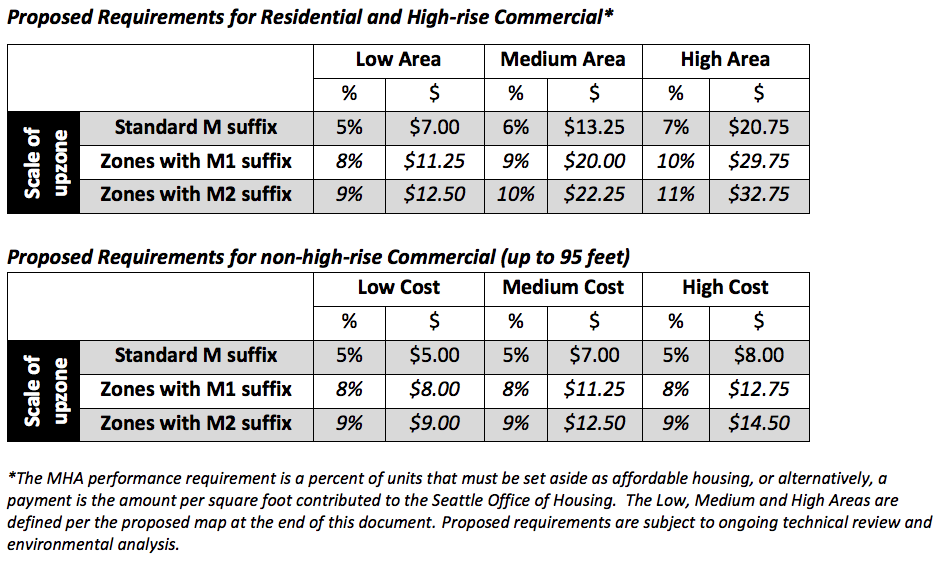

That said, the targeted approach in Alternative 3 does offer some advantages. Splitting neighborhoods into four categories with “high displacement risk and low access to opportunity” getting the slightest upzones and “low displacement risk and high access to opportunity” getting the biggest upzones–with apparently the most emphasis on adding the highest capacity M2 upzones that also provide the highest affordability requirements. For details, see the table below:

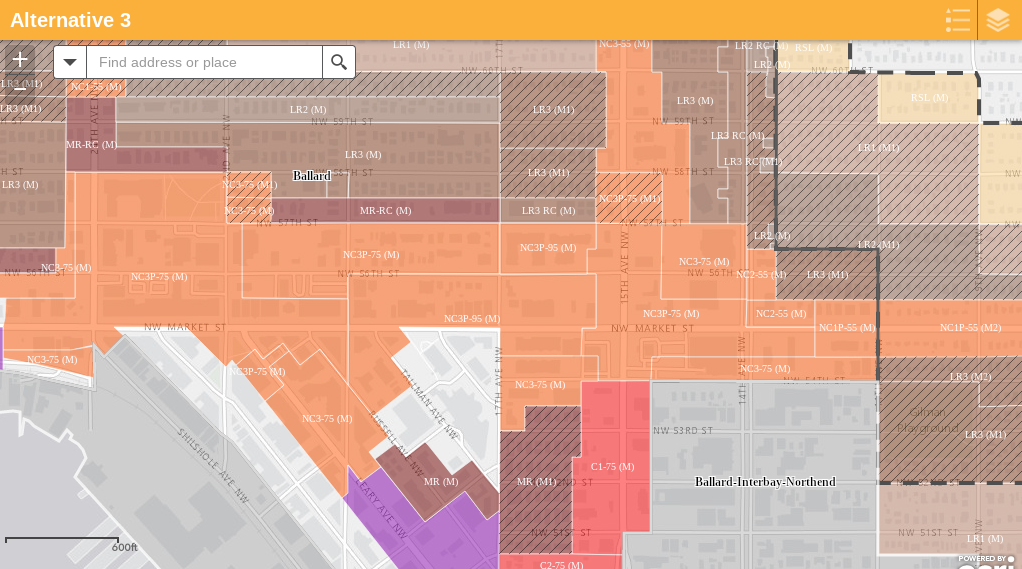

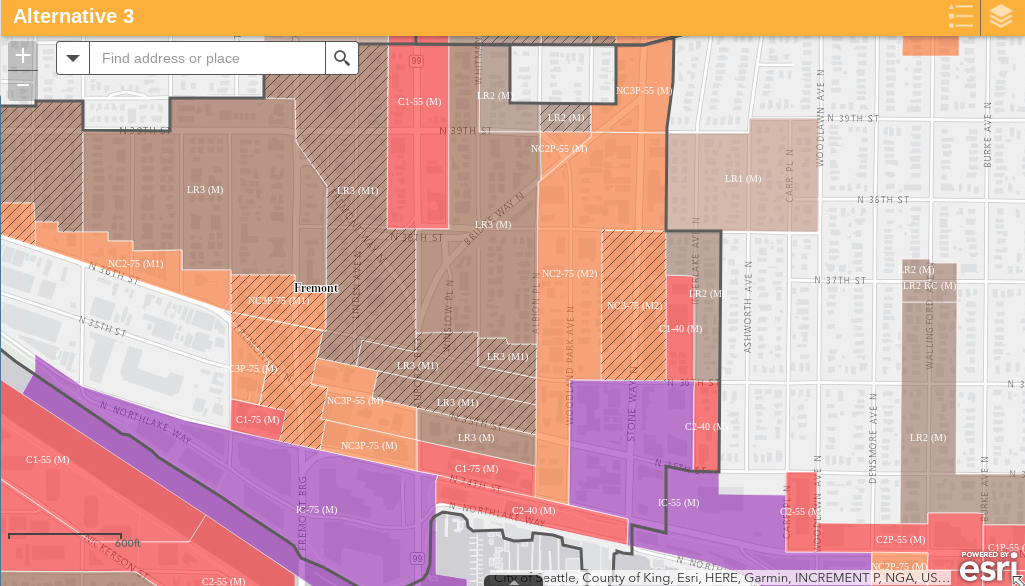

The result of that targeted approach is that upzones are scaled back in places like the Rainier Valley, Bitter Lake, and South Park while they are scaled up in places like Ballard, Fremont, Greenwood, Eastlake, and West Seattle Junction. Places with high displacement risk but high access to opportunity like 23rd & Union-Jackson, Columbia City, and North Beacon Hill would see “medium development capacity increases” in an effort to decrease displacement while also taking advantage of the high access to opportunity and amenities in these areas.

In theory Alternative 3 would not only increase the instances of bigger M1 and M2 upzones (with corresponding higher requirements), it would also lead to expanding urban village boundaries in neighborhoods with low displacement risk and high opportunity. In practice, the magnitude of the changes still appears below what some urbanists hoped. For example, it doesn’t appear anything beyond 95-foot NC-95 zoning is planned in Ballard, keeping everything mid-rise or lower. Plus Wendlandt said the only urban village expansions would be in areas already identified in the 2035 Comprehensive Plan, such as Crown Hill, East Ballard, Roosevelt, and West Seattle Junction. These expansions are denoted by the dotted boundary lines in the map.

In Fremont, Alternative 3’s M2 rezones are focused between Aurora Avenue and Stone Way–incidentally the area I highlighted as the growth center for both Fremont and Wallingford and playfully labeled Frelingford. Below N 39th St that swath will see NC-75 zoning, which is a healthy increase from today’s C-40 and LR3 zoning in these areas.

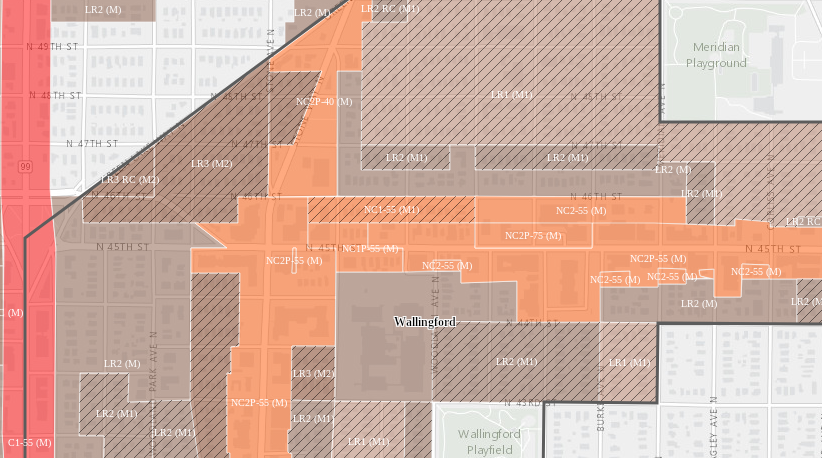

Meanwhile, Wallingford’s M2 zones will be focused in the northwest portion, although a triangle between Aurora Avenue, Green Lake Way, and N 50th St will be excluded. This portion has some of the best transit access in the neighborhood with the Rapid Ride E stop at N 45th St and the frequent Route 44 also nearby. Perhaps, the most remarkable thing about the Wallingford map is the M1 upzones replacing single family zoning with LR1 within the urban village boundaries. That expansion stretches low rise zoning from N 50th St to N 40th St west of Wallingford Ave N. The pronounced tapering of the urban village still exists to the east as it draw near the University District.

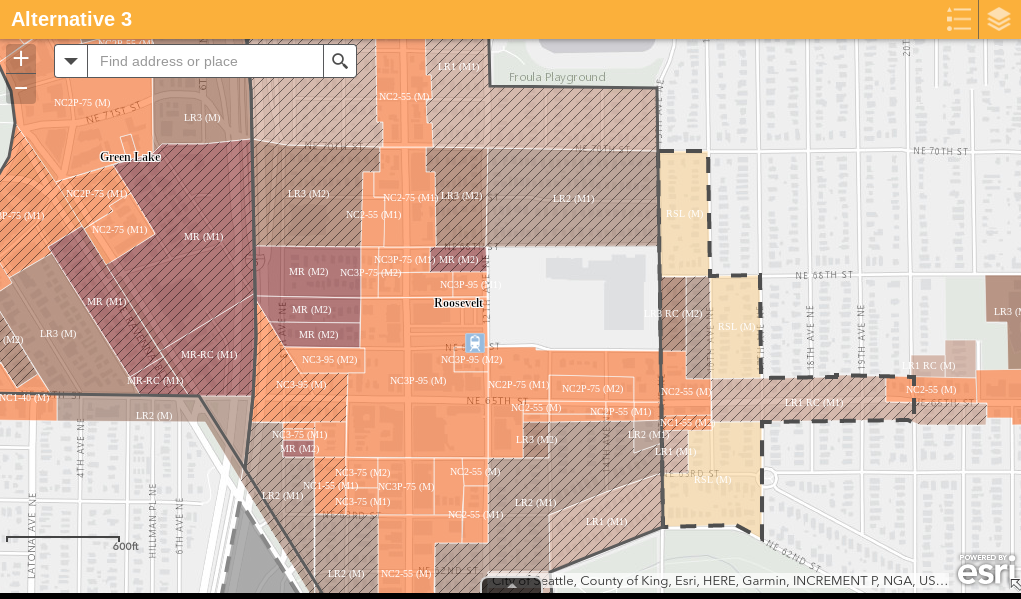

Roosevelt saw stepped up changes according to the Alternative 3 framework, but, like Ballard, saw nothing above 95 feet despite being next on deck for a light rail station, which should open by 2021. The worry, as we have covered before, is that NC-95 is not particularly enticing or buildable to zoned capacity since it requires a switch to steel or concrete construction without enough height to make the increased costs associated with those building types worth it. The Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda (HALA) committee report advised the city to use NC-125 zoning or greater instead of NC-85 (and rather than NC-95) to deal with this problem, but that has not materialized in many places so far. Following this HALA recommendation seems a wise move, particularly in high opportunity, low displacement risk neighborhoods.

One downside of Alternative 3 is that it scales back high-rise zoning in Northgate near the light rail station currently under construction. A large plot near the station would receive 240-foot zoning in Alternative 2 and it’s a publicly-owned lot with big plans for an affordable housing development. Despite being a high displacement risk neighborhood, there is no displacement risk on this particular parcel since it’s currently a parking lot. That site needs to be high-rise to support the County’s transit-oriented development plans. Alternative 2 clearly charts the better course of action here.

The displacement analysis dances around a thorny question for policymakers. Does development reduce the risk of economic displacement and thereby help at-risk neighborhood if it’s done in a smart way? A UC Berkeley Urban Displacement Project study re-analyzed and trumpeted by the California Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) suggests this is the case. Additionally, if we want to increase affordable housing production in these neighborhoods, should we use more M2 upzones in order to get higher affordable requirements? Would more targeted instances of high-rise be better for displacement in at-risk neighborhood rather than wide patches of mid-rise? The displacement question is an article of its own; so expect a follow-up article next week.

For now, it’s just good to see the wheels in motion. Here is OPCD Director Sam Assefa’s statement:

Implementing MHA is one of many actions the City is proposing to address housing affordability. We look forward to community input on the DEIS, especially on our analysis of impacts resulting from MHA implementation. Your feedback will help us finalize our recommendation on how to guide growth with additional affordable housing, while working to reduce displacement risks.

As for commenting on the plan, the Draft EIS is open to public feedback through July 23rd. Later this month, OPCD will host an open house and a public hearing. That happens on the evening of June 29th at Seattle City Hall. The open house kicks off at 5.30pm in the Bertha Knight Landes Room. During the open house portion, the public will able to review the alternatives and speak directly with City staff to learn more and provide feedback.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.