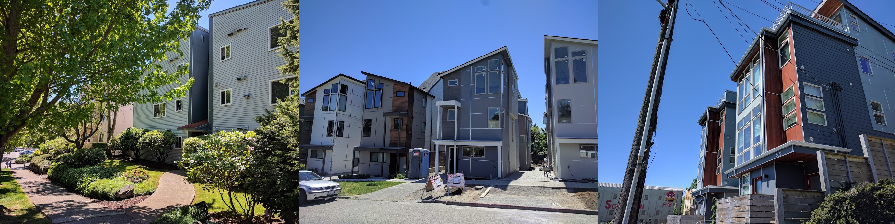

If you take the Route 44 bus all the way to the end of the line in Ballard, you’ll find yourself at the intersection of NW Market Street and 32nd Ave NW. Apartments buildings surround the intersection, but if you walk 150 feet west on Market Street, away from Ballard’s heart, you’ll have a single-family home on your right and townhomes on your left. Market Street is the boundary between urban housing and low-density single-family detached buildings. Lee Olsen lives on the wrong side of Market Street and he’s not happy about it, “To put us out here on the Elba Island is bullshit.”

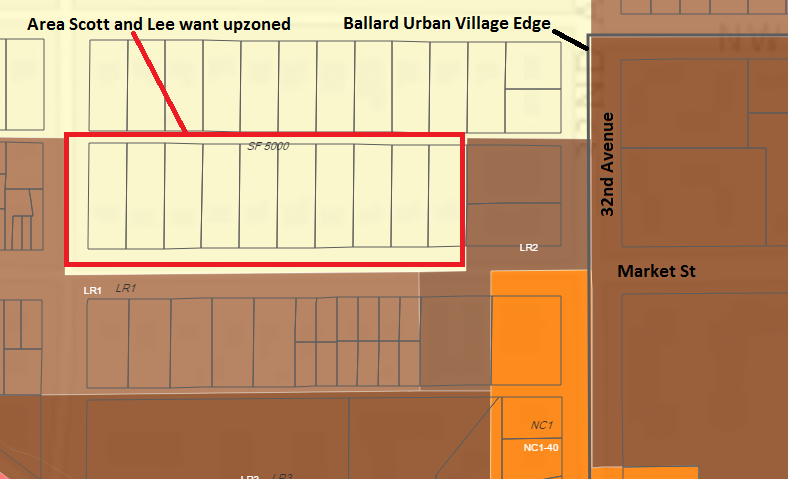

Lee’s referring to the detached single-family zoning his house lies on and his use of the word “island” isn’t too far off. When he walks out his front door he faces townhomes and duplexes, made possible by the low-rise residential zoning designation across the street. If he walks left or right, he sees more multi-family housing at the end of his block. Townhomes, and apartments bookend the block. He’s surrounded on three sides by multi-family zoning but his block is zoned for detached single-family buildings.

More townhomes are under construction in the neighborhood and it’s easy to see why. The 44 bus runs frequently during peak hours and Route 17 provides express service to downtown. The historic district in Ballard is only four blocks away. In less than fifteen minutes, you can walk to the public library, Adams Elementary School, the grocery store, the Ballard Locks, and Commodore Park. The sandy beaches of Golden Gardens are a 10-minute bike ride and Discovery Park is only a 15-minute bike ride.

Olsen’s neighbor, Scott Brown, is also supportive of upzoning and has been advocating for years. He’s been working on a way to be closer to his mother and originally thought building another structure on his property could be a solution. When townhomes started getting built in the neighborhood, he also realized selling his property and buying something closer to his mom could be a solution. Ideally he’d like to stay in the neighborhood he loves, near his wife’s existing job but without an upzone that isn’t a very plausible option.

He began talking with his neighbors, attending planning meetings, speaking with councilmembers, flyering his neighborhood, and even looking into the contract rezone process. These efforts appear to be making some progress. A contract rezone is out of the question since it would cost north of $10,000 and require an amendment to the Comprehensive Plan (including the Future Land Use Map), but Brown has successfully engaged his neighbors. He says that most of them support the upzone but two neighbors disagree.

One declined to comment for this article but the other, Adrian Lipp was willing to chat. Lipp lives on a different block, north of Olsen and Brown, across the alley. He’s lived in his single-family home for 17 years and is surrounded by single-family zoning. Lipp’s skeptical of Brown’s efforts and sees him attempting to change their neighborhood for his own benefit, pushing the cost of change onto neighbors like himself.

How The City Considers Zoning Changes

Generally, there’s very limited opportunity to rezone property because the City typically does it systemically, targeting areas that are prioritized after years of study and feedback, in accordance with comprehensive regional planning. Unfortunately for Brown, those opportunities only happen occasionally and he just missed one. His efforts and comments came too late in the Ballard Urban Design Framework process to have an impact.

Fortunately for him, the city is discussing something called HALA, a list of recommendations that includes rezones. The City Council is currently waiting on an environmental impact study before a vote on rezones–called Mandatory Housing Affordability—in Ballard. The policy requires new construction to contribute to affordable housing. If the study shows what the Council expects, they will likely vote to rezone portions of Ballard in the fall to increase development capacity and generate affordable housing. Planners indicated the study will provide two alternatives for Ballard, one of which includes rezoning Brown and Olsen’s block.

The Ballard rezone is a tiny piece within a multi-decade process to set requirements on new development. The rezones and affordable housing requirements are being done concurrently to protect the policy against lawsuits and generate the most affordability. The City Council already implemented the policy in Downtown, South Lake Union, and the University District. Initially, the policy was attacked from different constituencies. Developer lobbyists and their sympathizers feared it would kill development. NIMBYs said the policy was being pushed by developers and the rich. They also said it would destroy neighborhoood character and displace people.

Other groups were very supportive and many academics who study these types of policies generally support them. In fact, Seattle is already seeing successes where developers are scrapping their old plans and opting to pay for affordable housing. This means Seattle is getting more market housing and affordable housing dollars, both of which wouldn’t have existed without the policy. So far, it appears to be a win-win-win for urbanism, environmentalism, and affordable housing.

Whether or not the final HALA rezone includes Brown and Olsen’s block depends on the solution adopted by city council. The council could adopt an alternative released in the study or a hybrid and the feedback received from the public will determine that.

What Zoning Is Fair?

Seattle’s Urban Village designation is primarily meant to indicate where growth should occur in the city. The designation typically surrounds areas with amenities, such as schools, businesses, and frequent transit–areas like Scott Brown and Lee Olsen’s block. It’s not clear why their neighborhood isn’t included in the Ballard Urban Village. Regardless though, the line for the Urban Village is drawn at 32nd Ave NW adjacent to their block.

To Lee Olsen, this is deeply unfair. He says, “they’re taking $300,000 from me,” referring to the higher price-tag his home would have if he lived in the low-rise residential zone. “I have one to five years to sell,” since he’s expecting to move in retirement. Olsen’s not rich and has a slightly stereotypical working-class life in Seattle. He started working at 15, spent time on the docks, and then worked in the grocery business for 25 years. He’s fortunate to have been a union member and have a pension, but an additional $300,000 would have a huge impact on his life. He’s also not wrong about the estimate. A parcel that allows townhomes across the street sold in May for a little over $300,000 more than a home on his block, which sold in August of 2015 but isn’t zoned for townhomes. If he can save money during retirement, he’d like to help an independent mechanic get started on their own business. When I mentioned that the upzone would implement Mandatory Housing Affordability he appeared to have mixed feelings. He thought about it for a minute and then remarked that the cost would come out of his pocket since he’s a landowner.

To Adrian Lipp, who opposes the rezone, the existing zoning is fair because that’s the neighborhood he bought into and it’s been that way for years. Adrian is also working class and happens to have a very “Seattle” profession. He’s a mechanic on historic boat motors. This work allowed him to buy a house in the type of neighborhood he wanted, a single family zone.

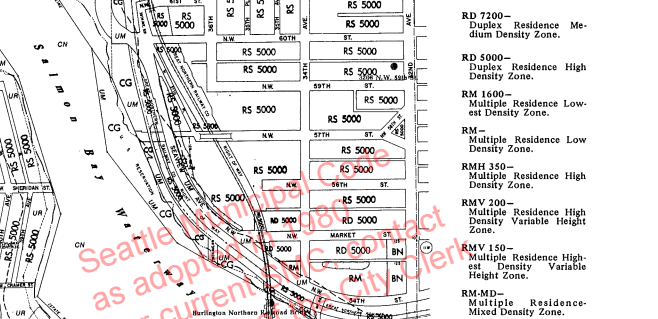

Lipp is right that the area has been zoned single-family for some time, at least since 1995. It’s also true that as late as 1980 the block was zoned for multi-family housing. Sometime between 1980 and 1995 it was changed to single-family. In fact, Olsen suggests the change happened after he bought his home in 1988, although records with the exact date couldn’t be found.

Lipp also sees his neighbors’ efforts as costing him. When I met with Lipp, he and friends were enjoying a beautiful sunny day on their back porch. He thought taller buildings could impact the openness and light of his backyard and porch. Considering how nice it was on the porch, it was easy to understand why this would concern him.

However, some nuance is warranted. A low-rise zoning designation would actually have a similar height limitation as existing zoning; there is only a five-foot potential difference in heights. The biggest difference is setbacks but Lipp’s property is across an alley so there would be a minimum of twenty feet between the edge of his yard and any new structures. Perhaps most importantly, stopping a rezone doesn’t stop change. Two blocks north of Lipp’s property there’s a brand new home. It’s a McMansion built out to thirty feet tall, the existing height limit in single-family zones.

Lipp also expressed concerns that the new housing doesn’t add much density or affordability. It’s sort of easy to see why he thinks this. Each new townhome has fewer bedrooms than existing single family homes. As for affordability, a townhome sold in 2014 for $629,000, not a price accessible to lower incomes.

But yet again, there is nuance. Typically four townhomes are built on a parcel that fits only one single-family home. The recently built townhomes have three bedrooms each, creating 12 bedrooms on a single-family-sized parcel. The single-family homes have four to five bedrooms, which means the low-rise residential zoning adds density, at least 7 bedrooms. Observations about traffic and parking corroborate this.

The concerns about affordability are also nuanced. The HALA rezones will require new construction to contribute to affordable housing. Right now, the aforementioned McMansions are being built with no contribution towards affordability. Even the old, existing single-family homes aren’t helping affordability. One on Brown and Olsen’s block sold in 2015 for $689,000, $60,000 more than the aforementioned townhome.

Lastly, the side of the block currently zoned for townhomes has a lot of old duplexes. If Brown and Olsen’s block isn’t rezoned, it’s much more likely the duplexes with renters will be the primary target for developers. However, if their block is rezoned, developers might purchase Brown and Olsen’s homes at a lower price than the rent-generating duplexes, possibly protecting those renters from displacement.

Lipp also mentioned a common complaint, more housing will worsen parking in the neighborhood. Perhaps surprisingly, Scott Brown mentioned the same complaint while advocating for the upzone. Brown bought into the neighborhood because it was a quiet, mostly single-family neighborhood. He said he knew his neighbors and felt comfortable with his daughter playing in the front yard or street. In fact, changes from the additional townhomes across the street helped clarify the situation for Brown. “The street changed as people built more,” Browns said, “we wouldn’t have moved here if this was here.”

While the neighborhood is no longer the one he bought into, he doesn’t oppose development. Instead, he just thinks it’s fair for him to have options. There are a lot of single family neighborhoods to choose from in the region and if he could afford to move he might be able to live closer to his mom. Alternatively, multi-family zoning might even mean he could stay in the neighborhood and build a place for his mother on the same property. Both Olsen and Brown agree that it doesn’t make sense their neighbor can sell their house for a much higher price and change the neighborhood but they can’t do the same.

Remarkably both Scott Brown and Adrian Lipp worry about similar changes. Regardless of the zoning, the neighborhood will change. They’ve just come to different conclusions about the best solution.

Soon the rest of the city will get a chance to provide input. The conversation among Lipp, Brown and Olsen regarding property values, density, parking, sunlight, and aesthetics will be expanded to consider the city’s larger goals regarding affordability, transportation, and how to plan well for growth.

Lines between single-family and multi-family zones exist all over the city and similar conversations are happening everywhere. It’s clear there is a lot of disagreement about what is fair. The conversations are personal and each person’s preferences impacts their neighbors. Planning exists to balance the private interest of each owner with what’s best for the neighborhood and city. Generally speaking, that’s why the city is pursuing the HALA recommendations. Specifically what those changes look like will be up to the City Council, which is expected to vote on changes in the next few months.

Owen Pickford

Owen is a solutions engineer for a software company. He has an amateur interest in urban policy, focusing on housing. His primary mode is a bicycle but isn't ashamed of riding down the hill and taking the bus back up. Feel free to tweet at him: @pickovven.