Seattle celebrated Bike Everywhere Day on May 19th, an inclusive alternative to Bike to Work Day that celebrates the idea that bikes are transportation and that everyone deserves a safe, accessible bike commute. Cascade Bicycle Club in conjunction with various Seattle Neighborhood Greenways neighborhood coalitions organized rides to Downtown from various parts of the city, most notably taking a lane on Rainier Avenue from Columbia City. Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) director Scott Kubly biked with this group of bike riders down to City Hall, where the neighborhood groups held a rally to push for the creation of a basic bike network in Downtown.

The basic bike network idea is pretty simple: get it done, fast, and cheaply. Connect the parts of the bike network that are already done or that are planned, by simply taking away the street space now. Permanent facilities can come later. Advocates rightly argue that bike commute rates will continue to stagnate at around 3% unless there’s a connected network for users to use, and the data backs that up.

SDOT recently released its 2017 Vision Zero progress report. The Urbanist will have a full write up on the City’s progress getting to zero serious injuries or deaths on our streets by 2030, but I want to specifically reference a specific section of the progress report. A centerpiece of the report is the Bike and Pedestrian Safety Analysis, or BPSA. I first reported on this study last year, which analyzes collisions in Seattle from 2007 to 2014 and looks for commonalities.

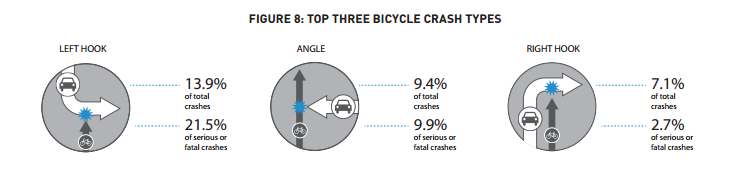

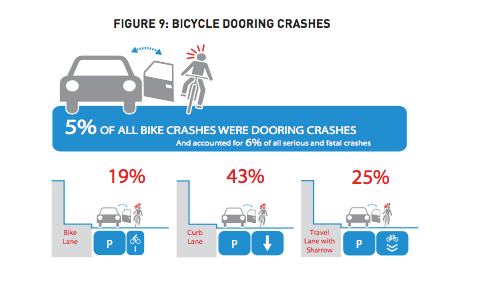

When it comes to bicycle collisions, the study found that one in five crashes, and one in four serious and fatal ones, are caused by either left or right hooks. Cyclists are in the biggest danger when they are entering intersections. In addition, the fourth most common bike crash type is even more preventable: dooring. Surprisingly, an even higher percentage of dooring collisions are serious or fatal than that of right hooks.

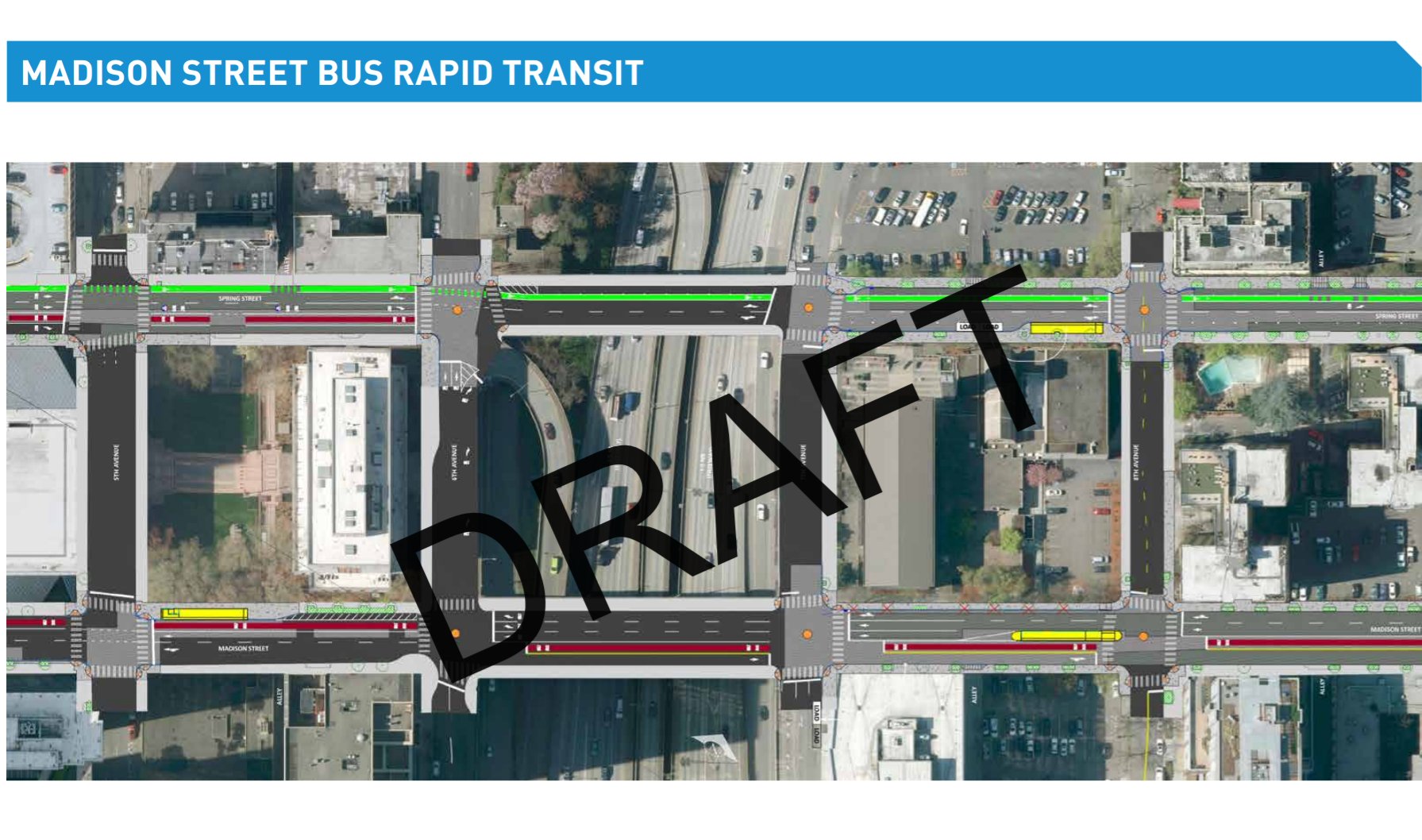

On May 20th, the day after the city hall rally in support of a safe bike network Downtown, SDOT crews could be found a few streets over from city hall, installing the first component of a centerpiece transit project, Madison Street BRT. On Spring Street crews were completely re-striping the entire street, making way for a bus-only lane on the right side of the street. But the existing painted bike lane was simply being moved over to the left side of the street–into the door zone.

The bus lane being added to Spring Street is beyond welcome, and should have happened years ago. But my question is when exactly will we start to take our own studies seriously if we aren’t incorporating the findings into every single project?

The department clearly made a determination that parking could not be relinquished on Spring Street, except on a small one-and-a-half block long portion. It’s worth noting that nearly an entire block’s worth of parking–both sides of the street between Second and Third Avenue–is not public parking, but reserved for police vehicles as part of the Puget Sound Violent Crime Task Force (PSVCTF). Without being intimately familiar with the needs of the PSVCTF, it is hard to imagine that the highest use of our street space is for police vehicles in a neighborhood with hundreds of vacant off-street parking at all times of day.

The full design for the Madison BRT plans for this area are below, with Spring Street and its bike lanes at the top, and Madison Street below.

But more important than the door-zone is the fact that we still aren’t protecting our intersections for bicycles or pedestrians. The only intersection improvements that were added for bikes were the green painted lines that indicate where a bike should pass through an intersection. At intersections where the direction of one-way traffic heads across the bike lane, like Fourth and Sixth Avenues, there is a high danger of someone getting left hooked, especially when there are two lanes of traffic that could potentially turn onto the one way. In addition, in front of the hotel at Fourth and Spring, a taxi-only zone has been left in place. Taxis certainly need loading zones in our ride-sharing-focused Downtown, but the design of the loading zone requires every taxi to enter a bike lane twice. In five minutes that I was there observing the loading zone, three vehicles blocked the bike lane at least partially.

SDOT has added a leading pedestrian interval to Spring across Fourth, which allows pedestrians to get a head start and become more visible before drivers start to turn left. But the wide-open design of the intersection still encourages two things that enable each other: excessive speed, and maneuvering vehicles around crossing people. If you need to swerve your vehicle around a pedestrian in an intersection to avoid hitting them, you’re going much too fast in the first place.

The way to solve this is with a protected intersection. Other American cities are trying them out, Seattle is being left in the dust. Spring Street is just another example of where advocates should be pushing for better design, but also where our transportation department should be using their own data to comprehensively change how they approach engineering and design. Apart from a few high-profile flagship projects, we haven’t yet seen that the switch in thinking has yet occurred at SDOT. While transportation doesn’t appear to be a big wedge issue in the upcoming mayoral election, it’s a big open question which candidates will continue to push SDOT in the right direction on this.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.