After weeks of speculation, the Seattle City Council appears to be rushing to put together a framework that could allow private bikeshare operators to get their bikes onto Seattle’s streets by the height of peak tourist season. Tom Fucoloro at the Seattle Bike Blog has been covering this story more intensely than anyone else in Seattle media, and thanks to his reporting we have a pretty good idea of what companies are eyeing the prime Pronto-free streets of Seattle.

Allowing a private bikeshare operator (or three) to come in and place bikes on our streets is probably very tempting to the bike-friendly members of the city council, who from all reports were left out of the loop on the decision to close down the city-owned Pronto bikeshare on March 31st. The decision by the mayor’s office to divert bikeshare funds elsewhere during an election year disarmed a political problem. Private bikeshare doesn’t come with as many political problems: no city money would go toward it, and the city might even come out ahead with revenue coming in for permits.

Josh Cohen, writing about the next steps for Seattle bikeshare at Next City, quotes Kate Fillin-Yeh, the director of strategy for NACTO, the National Association of City Transportation Engineers: “If something looks like it’s too good to be true, maybe it is,” citing the concern that cities with public-subsidized bikeshare systems could see themselves undercut by dockless systems that flood the market with loss leader pricing and the thrill of novelty. But is the danger to a city that has already had its bikeshare system fail even greater?

Seattle is still one or two years away from building out its Downtown bike network: there are still huge gaps in the cycling network Downtown and elsewhere. That was a major hindrance to Pronto, and it will be a major hindrance to the success of any subsequent bikeshare system before we have a complete network. But if a second bikeshare system in Seattle fails, it will be very hard to escape the narrative that Seattle and bikeshare just aren’t compatible.

One major issue with Pronto was the placement of the stations. As “dockless” bikeshare, the new potential private operators wouldn’t have to worry about where their stations are. However, stations come with big benefits for a transportation system. For one, you don’t have to go looking for your bike when you need it if you know the network reasonably well. Pulling up an app and having to locate a bike that may be several blocks away may not be sustainable for someone looking to hop a bike to get to work every day. Stations also provide an identifiable branding opportunity for the system. Someone just in town for a few days might not notice a few dozen bikes on the streets in their neighborhood when they might be more likely to notice bikes grouped together at stations waiting for riders. The dockless model may be both a blessing and a curse for private operators.

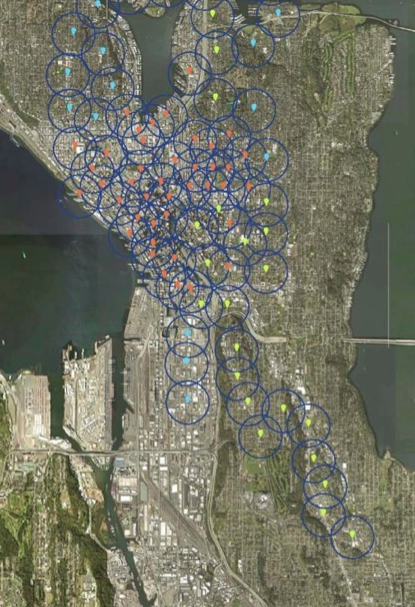

But the real test for a private system is how well can lower density areas be served, places where the bikes may not naturally end up on their own as much, compared to with a public system. After all, Pronto only served the relatively high-demand areas of Downtown, Capitol Hill, and University District. Serving areas like the Rainier Valley and the Central District was always envisioned, but didn’t pan out. But will a private operator be willing to subsidize service in one neighborhood from service in another, more popular neighborhood? And what can the city council do to encourage them to do so?

The Car2Go model will likely come up as a comparison to this problem. When first launching, Car2Go did not serve some South Seattle neighborhoods like Columbia City. Eventually they expanded after some public criticism and now serve most of the city. But Columbia City did not lack a safe car connection between itself and Downtown, unlike the bike connections currently. Bikeshare trips typically cover much shorter distances on average than car trips.

Then again, if the Pronto 2.0 proposal with Bewegen’s electric assist bikes was to be implemented, it only proposed serving the Rainier Valley with a linear string of stations along a corridor with limited bike facilities. One thing is clear: serving the entirety of Seattle with bikeshare is going to be tough. Getting a successful system up and running in our denser Downtown-adjacent neighborhoods should be much easier and that’s where any sensible system will start.

At this point in time, it seems very unlikely that Seattle’s leaders will forego the offers of private bikeshare operators in the hopes of returning a public bikeshare to Seattle’s streets. But the danger of such a system coming in and not becoming successful should be worrying, because it has the potential to cause any public model in the future to become a political non-starter. Even though most public bikeshare systems in the country do operate in the black, the standard that bikeshare, and not other forms of public transit, should pay for itself should not hold any water in a city that is desperate to provide alternative forms of transit. Public bikeshare is a public good that can do things that private companies cannot, and there is no reason to operate under the assumption that they are interchangeable. In any case, private operators should not slam the door on a public ownership model for the future.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.