The fate of much disputed MidTown Center may finally be decided. Lake Union Partners closed the deal yesterday on the coveted property with a $23.25 million bid. Moreover, the developer agreed to sell 20% of the parcel to the conservation non-profit Forterra who has partnered with Africatown with the shared goal of creating affordable spaces for homes and small businesses to ensure African Americans can continue to call this historically red-lined–and now red-hot–neighborhood home.

Excluded from other neighborhoods and cities with racial covenants and discriminatory lending practices, African Americans called the Central District home because they had few other options. As recently as 1970 the Central District was 73% Black, but it’s now estimated Blacks make up less than 20% of the neighborhood. With a shrinking Black population and mounting displacement pressure, Africatown has made it their mission to write African Americans into Seattle’s future. Many in the Central District’s Black community sees owning the land as key to changing the pattern of displacement and exclusion.

“We need to get our own cranes up,” Black Dot’s community manager Britney said at a protest at MidTown Center after Seattle Police Department dispersed a group camped inside the now re-located Black Dot, a community space and business incubator.

“If we don’t write ourselves into the future, there’s a good chance we won’t be in the future,” Africatown CEO K. Wyking Garrett said last year. “There was intentional exclusion, and now we need to have intentional inclusion.”

The Midtown Center deal propels Africatown toward that goal and vision for the Central District. Forterra and Africatown plan to build 135 affordable homes atop several storefronts and perhaps a small business incubator on their portion of the site. They will use a community land trust model to allow moderate-income residents a path to ownership. Meanwhile, Lake Union Partners aims to build at least 420 apartments, about 125 of those affordable via Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) and MFTE (Multi-Family Tax Exemption).

Lake Union Partners plans 420 apartments w/ about 125 affordable units, some of which would be req'd w/ MHA, and some likely MFTE. #HALAyes pic.twitter.com/WRSgh9mr0Z

— The Urbanist (@UrbanistOrg) May 24, 2017

“This is a huge deal,” Councilmember Rob Johnson tweeted, “They plan to perform instead of pay AND 20% of the land will be for a community driven housing project. MHA at work!”

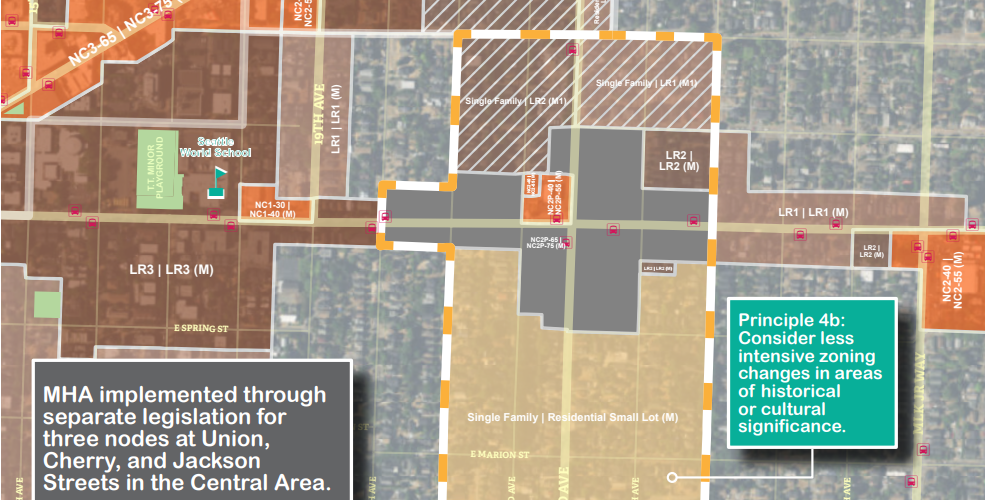

The Central District has not yet had its MHA neighborhood rezone, but the Seattle City Council appears set up to give an ordinance to implement MHA there, with its first hearing in the coming weeks. The affordable requirement–which Johnson said the developer has pledged to do on-site–will be 10% and the Lake Union Partners sees that as viable, as David Kroman reported:

But according to Joe Ferguson, a principal partner with Lake Union Partners, anything higher than 10 percent would have prevented the Midtown project from going forward. “From our perspective it would be extremely difficult to go above that, still make this partnership work and still have a viable project,” he said. Even the 10 percent threshold, he continued, means they will have less parking than they might otherwise build.

With or without a neighborhood-wide rezone, adherence to MHA would be triggered by the rezone Lake Union Partners wants from existing NC2-40 to NC2-65 zoning, gaining 25 feet in buildable height. The MHA draft map shows Mid-Rise (MR) zoning on the site which is functionally similar to NC2-65, allowing more height, but slightly less floor area ratio (FAR) which effectively caps height or the usage of the whole lot. If the Central District rezone is delayed, a contract rezone could be a possibility for the MidTown site.

At 10% of about 420 units, the 42 MHA units would be restricted to households below 60% of area median income (AMI) for 75 years. Whereas, the MFTE units making up 20% of the project (about 84 units) would be reserved for households below 75% of AMI for one bedrooms (85% AMI for two bedrooms and 90% AMI for three-bedroom units) for up to 12 years–the developer can opt out earlier but would lose the property tax exemption by doing so. Also note the MFTE requirement would be 25% if the developers does not includes enough “family-size” multi-bedroom units to qualify for the lower percentage. Together MFTE and MHA allow Lake Union Partners project to produce 30% affordable units, granted the MHA units will be guaranteed as affordable much longer. And that’s in addition to Africatown’s 135 units made affordable through a community land trust.

Ferguson’s comment suggests 10% inclusionary zoning requirements–which the City went with in high cost areas after pushback that the original 5% to 7% framework was too low–are not just viable in the Central District, but also may encourage developers to downsize underground parking, a frequent rallying point for urbanists. Downsizing parking structures rather than inducing demand for car ownership is a good way to make our neighborhoods more pleasant places while also cutting carbon emissions and helping our environment. Perhaps MHA will push us toward that goal and break developers out of their bad habit of oversupplying parking.

MidTown Center is kitty-corner from Liberty Bank where Africatown has partnered with Capitol Hill Housing among other organizations to redevelop the site of the region’s first Black-owned bank. The Liberty Bank Building will not only include 115 affordable apartments and a handful of storefronts, but also act as a gallery space for African American art, with some promising pieces coming together at the art open house last month. The Liberty Bank Building partners were also intentional about hiring minority contractors while bidding construction contracts. That attention to detail both in encouraging minority hiring and in honoring the Central District’s cultural heritage is why many are lauding the Liberty Bank Building as a model for development in the Central District.

23rd and Union has been called ‘ground zero for gentrification.’ Uncle Ike’s pot shop across the street has been a frequent site of protest. To some extent, we are still quibbling over what gentrification means. Some anti-gentrification groups have taken stopping gentrification to mean stopping all private development. Urbanists often point out that development reinvigorates neighborhoods and takes pressure off older housing stock and point to studies showing gentrifying neighborhoods with more private development have less displacement and better outcomes. Joe Cortright argued in The Atlantic gentrification is categorically a good thing. Nonetheless, the issue of ownership and cultural identity remains as black and brown people in historically red-lined areas like the Central District watch their neighborhood change. Africatown’s Garrett told The Seattle Times: “Normally people just throw their hands up and say, ‘Gentrification is inevitable and part of the market.’ We can do something different, and we will.”

Projects like Liberty Bank Building and deals like Africatown just brokered at MidTown Center suggests there’s a way out of the gentrification trap: We can build without losing the soul of a neighborhood.

The top featured image is by Kidder Mathews.

Africatown Organizers See Opportunity With Liberty Bank Site

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.