In the new book Drawdown, editor Paul Hawken, an environmentalist and author, lays out 80 solutions to reverse global warming by 2050: modest, attainable goals to slow the production of CO2 and accelerate sequestration. Ranked #54 in impact on the list is the creation of walkable cities. The book estimates that simply by replacing 5% of car trips worldwide with walking trips, 2.9 fewer gigatons of carbon would end up in the atmosphere and also save $3.3 trillion dollars in costs associated with operating those cars. Coupled with carbon reductions that could come with increasing bike trips and mass transit options, including high-speed trains, these solutions for cities are needed if we are going to change course from our current climate future any time soon. And a good place to look at exactly how we get there is in the master plans of cities like ours: Seattle is about to finalize its update to the Pedestrian Master Plan this spring.

Douglas MacDonald, former director of the Washington State Department of Transportation, laid out his low opinion of the Pedestrian Master Plan update in Crosscut last week. His point about the gap between the goals in the Pedestrian Master Plan and its implementation is a well intentioned one. The Pedestrian Master Plan lays out some very big goals: after all, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) has long said its goal is to make Seattle the most walkable city in America. But until we know exactly what SDOT envisions its implementation plan looking like, we should not be so quick to condemn the master plan as unachievable.

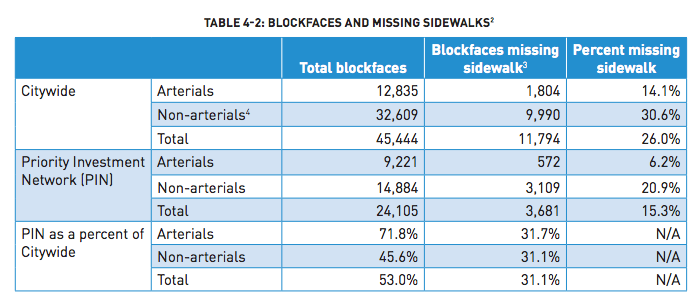

We know that we have a very long road ahead of us, so to speak, when it comes to getting sidewalks on every block in Seattle. MacDonald points out that Move Seattle only plans to fund 250 blocks of sidewalks, when there are 11,794 blocks missing sidewalks in Seattle. He concludes that because Move Seattle doesn’t fund anywhere near the number needed to complete the sidewalk gap, then the plan must be to fund the remainder with the next levy, which he rightly calls “absurd”. Transportation levies include too many different projects to allocate that much money toward new sidewalks. But what the master plan can only do is lay out what areas should be prioritized for new sidewalks, and the criteria makes a lot of sense. Areas near schools, transit lines, and where pedestrians have previously been injured by vehicles or unsafe road conditions. This still leaves a big priority network, one that we can’t fund with our current levy.

But the alternative would be a master plan that sells itself short. When creating the Bicycle Master Plan, SDOT did not assume that they wouldn’t be able to implement an entire city-wide bike network because it would be too expensive, even though the total costs were estimated at $391 million to $540 million. Move Seattle, being $930 million in total, will not fund anywhere near that, particularly as costs are escalating for projects like protected bike lanes. But the job for dealing with the disparity is and should be left to the implementation plan. Can you imagine a master plan that doesn’t even acknowledge that sidewalks would be desirable in your neighborhood, particularly if your neighborhood is close to a school or transit line?

Another key point that MacDonald makes is that SDOT doesn’t have a good idea of where sidewalks are in bad condition: this is true. The city council, mainly at the urging of the Pedestrian Advisory Board, added money to this year’s budget for a sidewalk assessment. But the idea that we need to pause the master plan until we have an idea of what our sidewalk conditions are is a bit silly. The master plan lays out how the department will approach sidewalk repair, but it doesn’t lay out specific sidewalks to get repaired. We would not hold off on a plan to fix potholes until we had a log of every single pothole in the city–or one thing more would be created by the time the study was completed. The same is true for sidewalks that are in poor condition. This is a reason to push for more funding, not to throw out the plan. Waiting on the sidewalk assessment would be very unlikely to provide us with a different outcome.

The Pedestrian Master Plan is not perfect. We have dug into it critically in the past year as it has worked its way toward city council, and the plan has evolved in response to criticism. We were critical of the targets that were laid out in the plan: for example, there was no target for pedestrian mode share, only a desired trend line of increased pedestrian mode share. The plan being reviewed by the city council now includes a target of 35% mode share of all trips by 2040. The funding levels for pedestrian trips compared to other spending is absolutely an issue, and one that Seattle residents need to be vocal about during the upcoming mayoral and city council elections. New issues will come up: it’s pretty clear that signal technology SDOT is keen on installing on busy traffic corridors does not work well for pedestrians.

But the fact that our plan is ambitious because our goals are is not reason to surrender to defeatist tendencies and say that Seattle will never be walkable. Seattle can and will be more walkable than it is today, and making sure that it is is our job. We have our work cut out for us, but I think we’re up for the job.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.