Seattle, we need to talk. It’s undeniable that we are creating the model for an urban high-tech corridor that eschews the inefficient sprawl that has been so entrenched in the American tech sector for the past few decades. Out with the sprawling corporate campus, in with the vertical one. Instead of creating your own suburban style streets, utilize the existing street grid and harness the power of an urban center city. It’s pretty clear how beneficial this new path will be for the planet, and for the economic health of cities themselves.

South Lake Union (SLU) and Denny Triangle are this model. And if Seattle as a whole is going to rebel against increased density in order to relieve the intense pressure that economic growth is putting on housing prices, we can all agree that making the SLU urban center more dense with both housing and office space is one of the most practical solutions we have.

Unfortunately, we forgot to do one thing on the way to making this a reality: leave out the cars.

Take a scroll through the dozens of building projects currently going through the design review and permitting process in South Lake Union and Denny Triangle. The number of parking spaces planned for an area with a street grid that’s already packed with cars during peak periods is astounding. Several planned developments include over 1,000 parking spaces each, including 1120 Denny Way project and the 300 Boren Ave N project. Amazon’s three-tower complex down Westlake at Virginia Street, in addition to being home to the photogenic biospheres that open next year, will also be home to more than 3,000 parking spaces in total.

Denny Triangle has 33 projects w/ almost 10,000 homes and 3.5M sq ft of office. (But will take years to build out and not all will happen.) pic.twitter.com/78fU3i5b2y

— Seattle in Progress (@seattle_nprgres) March 31, 2017

Denny Triangle projects will include 10,000 parking spaces: about 5,000 in residential buildings, 3,000 in office and 2,000 in mixed use.

— Seattle in Progress (@seattle_nprgres) March 31, 2017

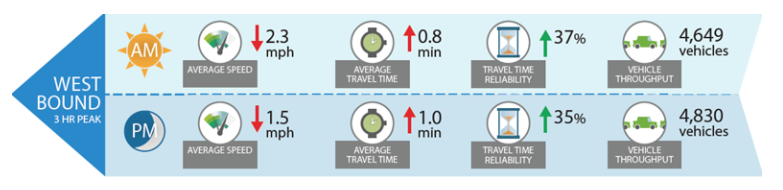

After spending $140 million on upgrading the Mercer Street corridor to “clean up” the I-5 congestion, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) has only ended up proving the efficacy of induced demand and the futility against trying to build our way out of a car-heavy present. Now the department seems intent on placing a big cherry on top in the form of a million dollar traffic signal timing improvements that simply seem to reprioritize car travel during peak hours to I-5 eastbound.

Transit riders and pedestrians in the corridor have immediately noticed the impact that the new timing is having on their travel around Mercer. Because there isn’t any east-west public transit on Mercer in SLU, prioritizing east-west travel means deprioritizing transit. How exactly SDOT is planning on running a RapidRide route up Eastlake through Fairview while still prioritizing traffic onto I-5 is only one of the upcoming challenges, to say nothing of the transit riders currently wondering why their bus is sitting at Mercer behind cars blocking the lane.

As for pedestrians, the new signals are frequently cutting pedestrian crossing time short while still allowing traffic to move in the same direction. When traffic is stop-and-go, and no vehicles are moving through the intersection anyway, this encourages pedestrians crossing against the crossing signal. Creating an environment where the pedestrians must judge for themselves if they are going to wait for no perceived reason or just go for it sounds familiar–it’s exactly what happens near our at-grade light rail stations on Martin Luther King Jr Way S where pedestrians can sometimes wait 10 minutes for a walk signal that grants permission to walk a few feet.

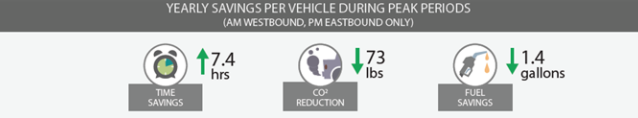

The documentation around the Mercer ITS (Intelligent Transportation System) is really quite remarkable as it shows just how deeply entrenched the commitment to Level of Service standards are at SDOT, despite all of the seeming progress toward complete streets, prioritizing people movement instead of vehicle movement, and Vision Zero. The webpage for the ITS system actually touts a carbon savings of 73 pounds per vehicle using Mercer during AM westbound and PM eastbound, as if that wasn’t offset by additional traffic pouring into the corridor now and in the future. Something is seriously rotten in the state of the Muni Tower.

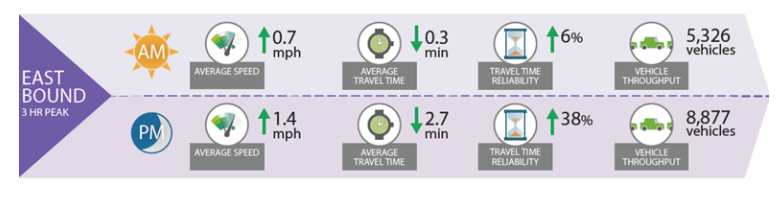

Whether or not traffic computers are able to squeeze 2.7 minutes for every eastbound car on Mercer right now doesn’t matter because it simply is not sustainable. SLU development is not slowing down, parking garages are not getting trimmed down, and the new state highway portal that will be opening smack dab in the middle of SDOT’s optimized Mercer corridor will not help matters.

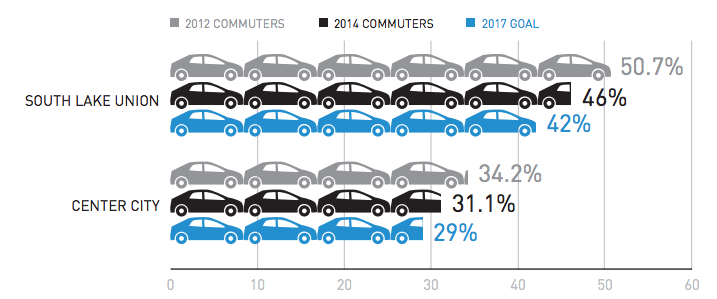

That’s not to say that things aren’t moving in the right direction per se. The blunt number of jobs in SLU and Denny Triangle means that everyone simply cannot drive to work by the laws of geometry. But the area is lagging significantly behind central downtown in commute trip reduction.

The only way to speed up this process and get SLU to the exact same levels as the Center City is to stop trying to “rebalance” traffic and prioritize the modes that need to be prioritized. Ensure that transit has signal priority, that pedestrians don’t have to wait decades to cross a single street, and stop rewarding the onslaught of off-street parking construction with street space. There is only one direction for SLU to go if it is to continue being a model for a 21st century tech hub. The sooner our department of transportation gets that, the better off we’ll be.

Title image credit: Concept design for the SR-99 North Portal, completely devoid of pedestrians or people on bikes, courtesy of the Washington State Department of Transportation.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.