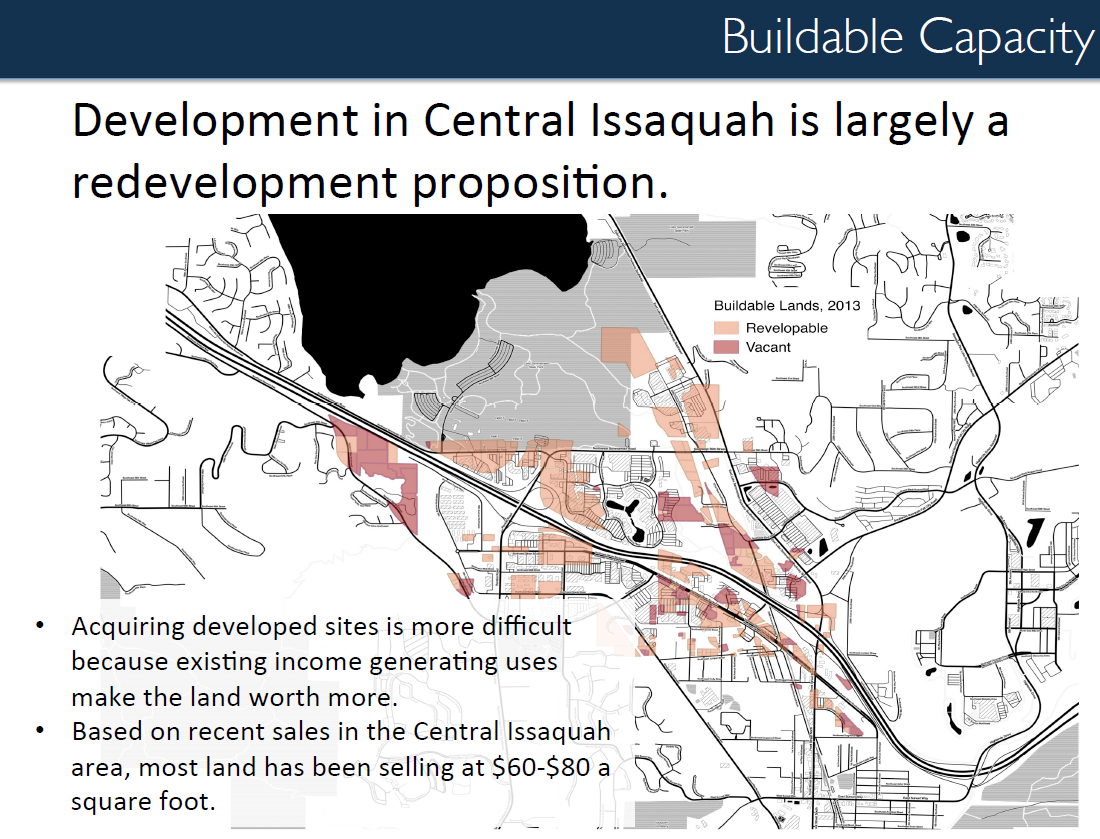

One of the primary reasons for the Central Issaquah development moratorium is the lack of Vertical Mixed-Use (VMU) development naturally emerging. Projects in the development pipeline are mostly big box retail with surface parking, and a proposed Les Swab tire store on Gilman helped spur the council to action last fall. Additionally, the city is concerned about net loss of retail and does not want to replace existing shopping malls with apartments with no commercial space.

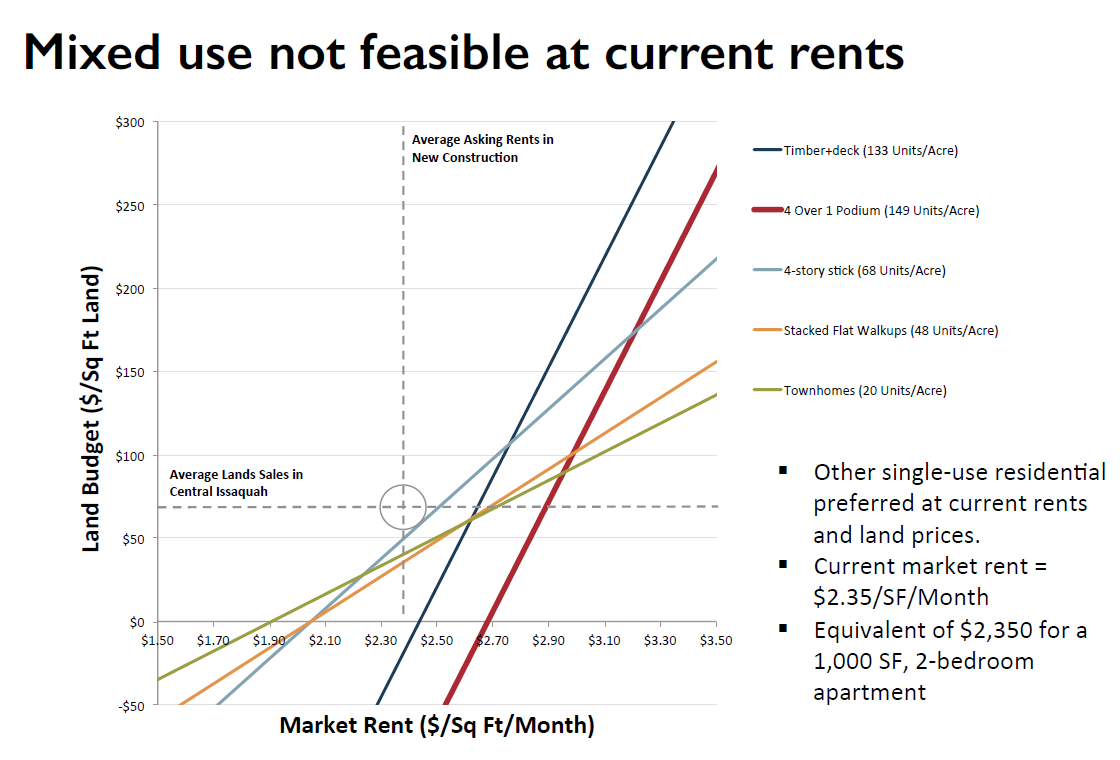

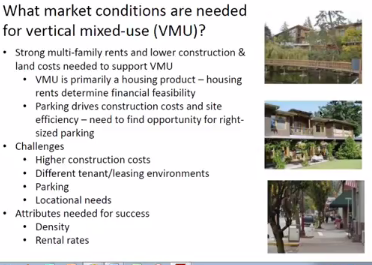

In September 2016, city staff presented a study by Eco-Northwest that said Central Issaquah was not yet ready for VMU, primarily because residential rental rates are not yet high enough to justify the higher construction costs of VMU. Parking is a big issue with VMU–it takes up lots of precious, expensive space, and structured parking is expensive to build–so being able to minimize parking spaces in a building can go a long way towards making the finances pencil out. The study estimated the market was five to 10 years away.

The city, however, cannot simply wait for VMU to happen because Central Issaquah is ripe for development right now. As was stressed repeatedly during the Land & Shore committee meeting on March 2nd, there is a “once every 50 years” opportunity to redevelop a parcel. Buildings that are built now will generally stick around for 50 years, and what gets built today will dictate the urban environment of Issaquah for more than a generation.

As a part of the moratorium work plan, city staff presented a toolkit of incentives and regulations to support VMU development.

Incentives (to support VMU):

- Build infrastructure;

- Suspend density bonus requirement;

- Waive fees;

- Help Assemble properties; and

- Development or partnering agreements.

Regulations (to deter non-VMU):

- Increase floor area allowances;

- Require multi-story development;

- Require structured parking (all or some);

- Require VMUs in defined nodes or everywhere;

- Require minimum square footage or percent of ground floor as retail; and

- Restrict specific uses.

Two interesting notes:

- The staff viewed the current density bonus requirement as a disincentive, saying the city is “not going to get five more stories because of the building type,” i.e. five-over-one VMU.

- The staff highlighted that minimum floor area allowances or height don’t necessarily deter non-VMU, for example multi-story storage units.

Most of the discussion focused on building infrastructure, with Kirkland, Redmond, and Bothell seen as models to follow. Investments in amenities such as urban parks and improved transportation infrastructure helped spur VMU development, with city-provided parking to help support the transition from a low-density, suburban commercial core to the current denser city centers. Interestingly, both Redmond and Bothell have had success building walkable, transit oriented development with future high capacity transit fully funded but not actually built out.

Interviews with these peer cities said it is important that VMU is market driven, to avoid vacancies or other unintended issues. This leaves Issaquah in a tricky Chicken or Egg predicament–do we do VMU once infrastructure is in place, or build VMU to help spur infrastructure? How does the city signal to the private sector that VMU development is worthwhile? The council seemed keen on building out infrastructure ahead of VMUs, particularly along the Gilman corridor, so I’ll walk through three “legs” of investment the city is planning.

Three “Legs” Of Investment

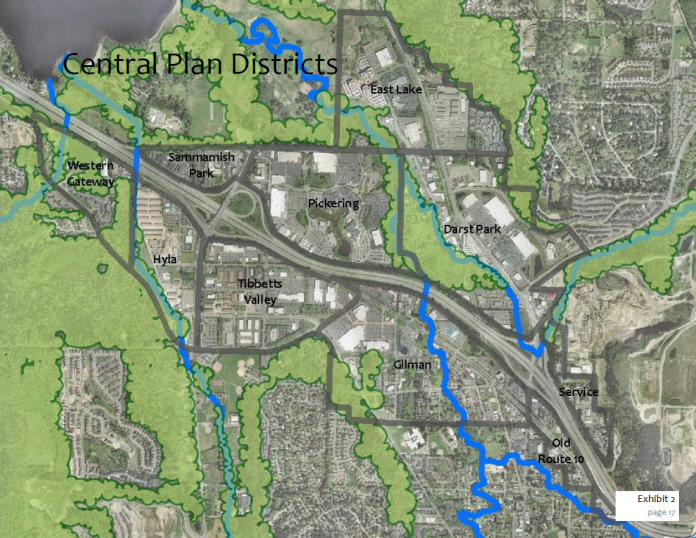

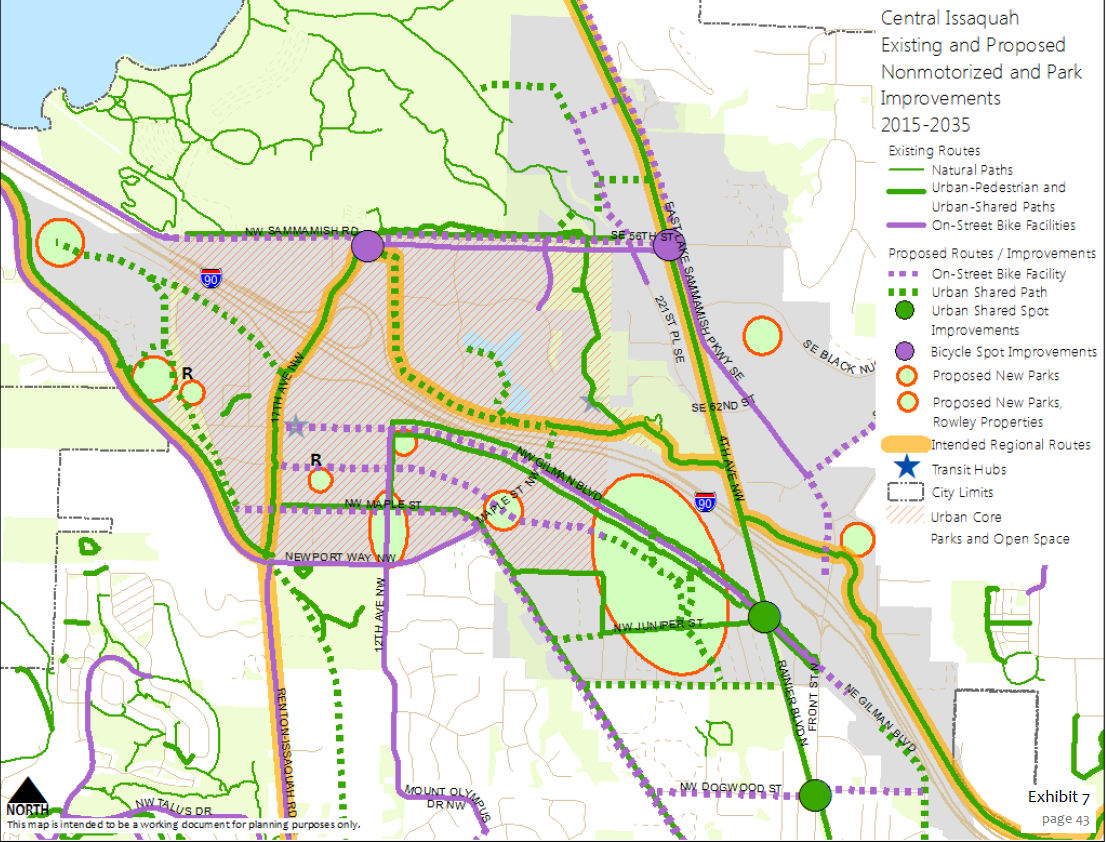

One leg of this investment is parks. Issaquah takes great pride in the “green necklace” that surrounds the city and it looking to better connect the regional trail networks of Lake Sammamish State Park, Mountain to Sound, and the Issaquah Alps to the networks of trails, smaller parks, and creeks that run through the city. The city wants to add an indoor/outdoor recreation facility in East Lake plus at least one more neighborhood park elsewhere in Central Issaquah. The city has had great success with transfer of development rights previously and hopefully these could be used to acquire land for another park.

The next leg of the investment is building out the street grid. As you can see in the above map, the city wants to roll out bike facilities and/or shared use paths on basically every single road in Central Issaquah, and the Central Issaquah Plans specifically calls out funding and implementing a Bike and Pedestrian Master Plan (and gives a shout-out to a bike share).

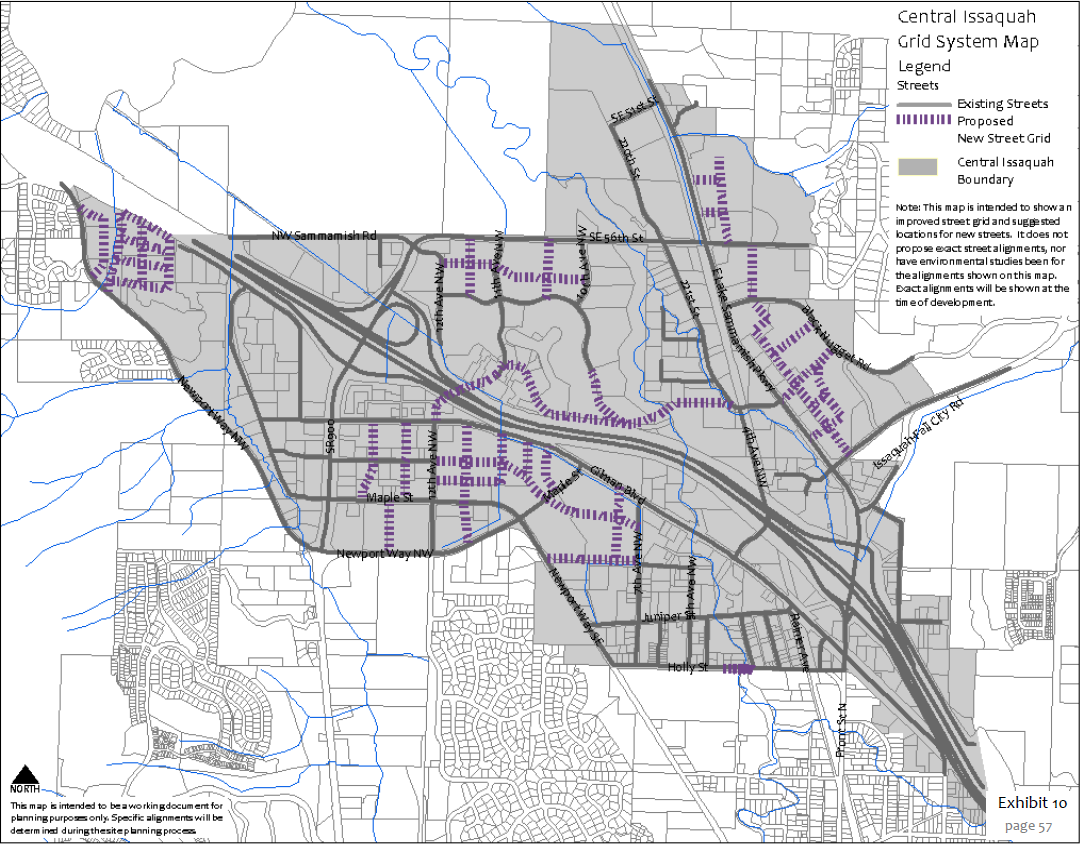

More ambitiously, the city wants to completely remake the street grid to improve connectivity within and between neighborhoods. Within neighborhoods, the city wants to break up the existing super blocks as seen in the map below. Between neighborhoods, the city wants to bridge the major barriers breaking up the grid, freeways and waterways. Across I-90, the city wants a multimodal crossing at 12th Ave plus two pedestrian crossings, one at Tibbetts Creek and one connecting Maple Street to the Pickering Trail. The city also wants pedestrian bridges over Issaquah Creek at both NW Holly St and SE 56th street.

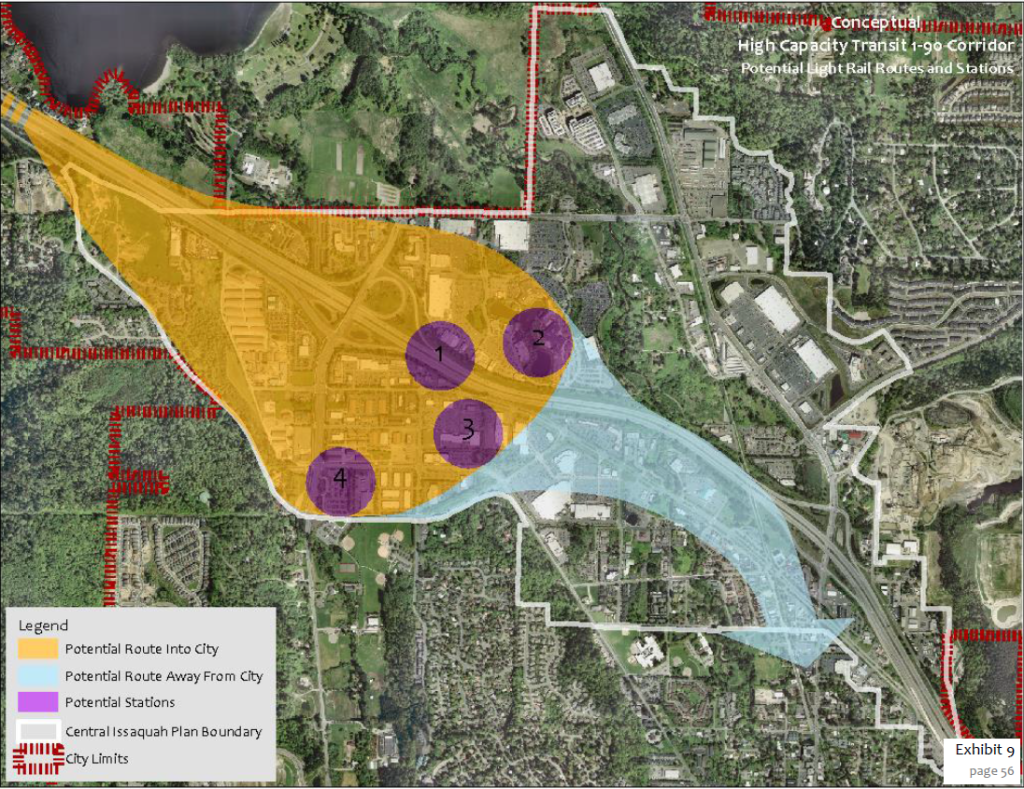

The final leg is transit. The existing transit center is adjacent to SR-900 and a park-and-ride and is very much designed to efficiently serve cars and buses. It is not centrally located so the ST3 light rail station will likely be much closer to I-90/Gilman Blvd to not only anchor the Tibbets Valley urban neighborhood but also bring the Pickering and Gilman neighorhoods into the walksheds. The city is keenly aware the exact station location will go a long way towards creating the “there” there in Central Issaquah.

On the regulatory front, the council seemed to lean towards strong deterrence in all neighborhoods where VMU is a part of the intended neighborhood vision, as there is currently a disconnect between vision and zoning (I’d recommend checking out pages 18-22). As one councilmember put it, “there sure are lots of pictures of VMU in the plan,” and people will be upset if that’s not what actually emerges.

There was some good discussion around placement and orientation of ground floor retail, and the committee asked staff to come back with a map detailing block-by-block where ground floor retail is envisioned in the neighborhoods. More generally, staff is working on a parallel moratorium work item, Neighborhood Visions, and these visions will incorporate language on VMU when relevant. Once the community has a more specific vision of where and how it wants VMU within the neighborhoods, staff will propose regulations to deter development that doesn’t fulfill these visions.

My Take

I write about Issaquah because I believe what happens here is important for the greater region: Central Issaquah is a regional growth center and the terminus of one of our rail lines. The city wants a proper urban core–something as vibrant as downtown Kirkland but much larger–but can’t seem to pull it off even in this red hot real estate market. NIMBYism is not really an issue, as historical Issaquah with its small town charm is not a part of the growth center. What’s missing?

I believe that very strong non-VMU deterrents should be implemented so the region doesn’t fumble away a golden opportunity to build a vibrant, urban neighborhood. I believe the city should build out some urban infrastructure preceding urban development, but ultimately private investment should be sufficient to build the actual VMU development. I do not, however, know what this public infrastructure should be. What makes a city before there are people to make it?

What would you do? How would you VMU?

AJ McGauley

AJ McGauley was a temporary transplant in the Seattle area, living in East King with his lovely wife for five years before returning to the great Midwest. Having lived in nine very different cities in the six years prior to moving to Washington, he discovered the wonky side of urbanism after reading The Urbanist and is interested in why cities grow (or don’t grow) in different ways. He worked for Sound Transit and can still be found riding transit for fun.