That The Urbanist disagrees with Sightline Institute about Seattle’s Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program is hardly news. I’ll try not to beat a dead horse. The latest piece from Sightline’s Dan Bertolet presents his “static pro forma” numbers in the low-rise zones. Bertolet’s long-running argument that the program would work better as a “naked upzone” with no MHA requirement is a bold claim that deserves closer examination and we can look at the upzone without MHA numbers he provided to illustrate the point.

Pro Formas Are A Limited Snapshot

Pro formas–the budgeting spreadsheets developers use to demonstrate the financial viability of their projects to banks and investors–are a finicky thing to get right, even for somebody who does them full-time. And even when they’re right, they represent a snapshot in time rather than a guarantee of what will happen in the future. Sometimes, rents go up even in the time it takes from breaking ground to renting out a completed project. That means the pro forma indicating a certain profit level may reap higher profits, and the reverse is also possible. A convincing pro forma is crucial for a project to secure financing, but they don’t necessarily chart a project’s real future, especially if market conditions change unexpectedly.

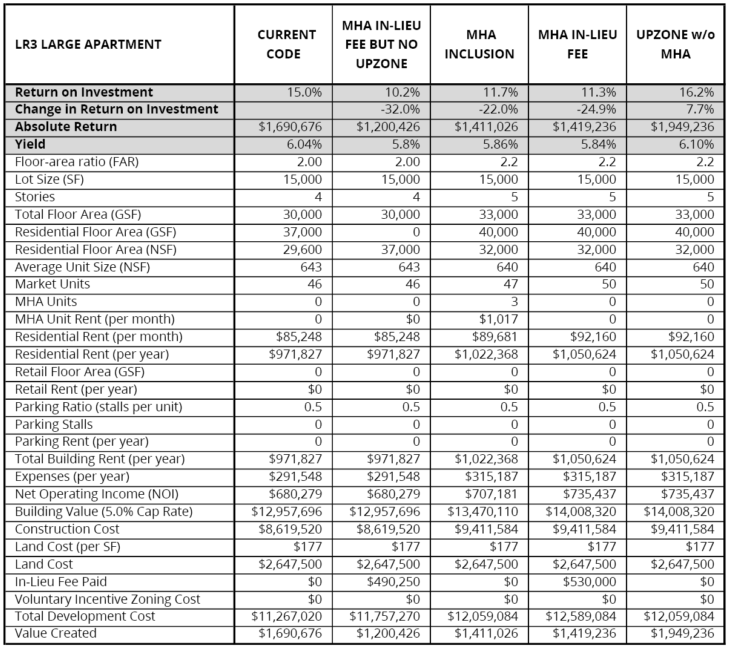

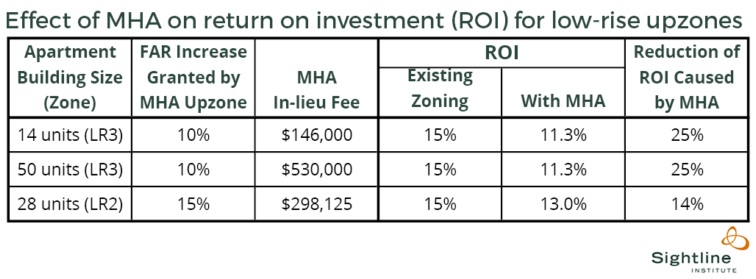

Bertolet’s “pro forma” might not even be far off. But that he chose to start his analysis from a baseline of 15% return on investment (ROI) is arbitrary. Projects are going to come in at a spectrum of returns, and in the current boom, many projects are likely reaping higher returns than 15%. And while Sightline paints slightly diminished returns on investment for developers as a doomsday scenario, it’s not clear that it is. Notably, Sightline doesn’t include leverage (borrowing) in their “pro forma” examples instead using 100% cash on cash returns. As such Sightline’s pro formas aren’t very realistic because most developers do use borrowing to amplify their investment and decrease their personal risk. What’s more, Bertolet calculates the ROI number from year one; one year in is rather early for an investment to mature.

Hypothetical pro formas by people on the sidelines–while interesting–do not really rise to the level of empirical housing research. And, by the way, developers rarely release their real pro formas because they reveal a good deal about their assumptions and business practices. As for empirical research, The Urbanist’s Owen Pickford has laid out relevant studies and interviewed experts, and he concluded the research that has been done on inclusionary zoning conflicts with the narrative that it’s a fragile program; nearly all the academic research found no impact on supply, or minimal impacts from inclusionary zoning across many different designs, markets and municipalities.

Musical Chairs Analogy

The framework underlying the supply mindset is that any unit deferred or eliminated increases the cost of housing and prices somebody out. Bertolet uses the musical chairs analogy to illustrate this point: “Regulations that hold back the production of market-rate housing ultimately hurt the city’s lowest income individuals and families most through the housing market’s cruel version of musical chairs that results in fierce competition for what’s available in the city and leaves no homes for those with the least to pay for them.”

Clearly building enough housing to accommodate a growing population is a worthy and needed goal. But the musical chairs analogy falls short in a few ways:

- This “game” can always add more “players.”

- The new “players” tend to be wealthier and able to out-compete older players.

- The new market-rate chairs tend to be more expensive than comparable old chairs.

- Many of the lowest income renters already rely on reserved seats (i.e., rent-restricted units).

- Housing consists of a series of distinct markets rather than a single unified “game.”

Therefore, helping the lowest income individuals should involve creating more rent-restricted units, not just market-rate chairs. Building rent-restricted units in booming neighborhoods (like MHA does) ensures at least a baseline level of economic mixing of classes. More sophisticated critiques of MHA have focused on how it leaves a gap between those who qualify for rent-restricted units and those who can afford market-rate units. This is a problem, but an easier one to address than the alternative of creating no new housing supply below 80% of the area median income. It takes less subsidy to help someone at a moderate income level than a low income level.

Land Ho!

Sightline’s preferred solution of just doing the upzones without MHA could very well result in a big spike in land prices. Their pro forma illustrates the point. The 15,000 square foot lot zoned LR3 gains a million dollars in value and about a quarter million dollars in absolute return in the upzone without MHA scenario. Notably, that’s assuming land costs are the same across all scenarios; on the contrary, land values are likely to respond to the zoning changes. Land sellers would note the increased value and ask for higher prices. By avoiding the affordability requirement, developers would likely end up paying more to landowners. MHA moderates the tendency for upzones to send windfalls to landowners.

Bertolet has argued higher land prices are good because it would encourage more landowners to sell to developers who then create more housing supply. This may work on a certain scale (insofar as landowners are rational actors). However, using the market to build our way to affordability runs into some problems. First, saturating the luxury market is easy enough but few developers focus on the lower-end market, and filtering takes time. Second, enough capital has to exist to build out the increased housing potential. Third, if the building binge starts working and prices flatline or even dip, developers would still have to continue building even as banks tighten credit and their pro formas start looking less enticing.

In conclusion, Bertolet might have a minor point that the City could have been a bit more generous in the low-rise zones. But this is hardly the intractable problem he makes it out to be. For one, the City is creating additional low-rise zones with its rezone process. Some urban villages will see single-family residential zones converted to LR1 or LR2 low-rise zones, meaning Bertolet’s analysis doesn’t apply to them since single-family residential zones weren’t buildable before as multi-family apartments, anyway. In the existing low-rise areas that are getting a less dramatic 10% to 15% floor area ratio (FAR) boost, it’s possible land values will absorb some of the developer costs. Or a developer may decide a project with a slightly smaller return on investment is still worth building.

Thinking of housing as a single unified game of musical chairs leads us to overlook some factors. The fact that this game can add a lot of players means adding chairs doesn’t necessarily mean less competitive players (poorer people) won’t miss out on a chair and get eliminated from the game. That’s what we already are seeing: even as we build record numbers of apartments, increasingly poorer Seattleites are getting displaced to the suburbs, farther away from services, jobs, and the communities they’ve built. There is a possibility filtering works well and rapidly so that an influx of new market-rate units serve the least among us indirectly, but more likely we need the influx to include affordable units immediately to begin reversing the displacement trend. Inclusionary zoning serves that goal while shifting the paradigm about much needed upzones from developer giveaway to affordability tool.

Featured image is by Moheen Reeyard and used via Wikimedia Commons.

Misleading Sightline Articles Undermine Inclusionary Zoning Effort

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.