The Seattle Times Editorial Board (STEB) publishing bad transportation ideas is hardly a surprise, but, even for them, Sunday’s editorial took their trolling and scapegoating to a whole ‘nother level. A new art form may be blossoming right before our eyes. The STEB has an unique ability to work its favorite scapegoat targets–bike lanes, the increasing number of City employees, and transit lanes–into one neatly wrapped package just barely holding together a string of delusions and outright lies.

Why not start with the headline: “After yet another epic jam, it’s clear Seattle’s decisions about traffic must include cars”? When have we excluded cars from planning pray tell? Anybody intimately involved with street use decisions knows that the interests of cars still dominate decision-making and concessions for transit, bicyclists, and pedestrians must generally be clawed from policymakers through long and concerted pressure. That’s how we get a $4 billion tunnel and a nine-lane Alaskan Way surface highway (with ferry queue lanes) replacing the viaduct. (Note to STEB: in sum, that’s actually more capacity than the viaduct holds.)

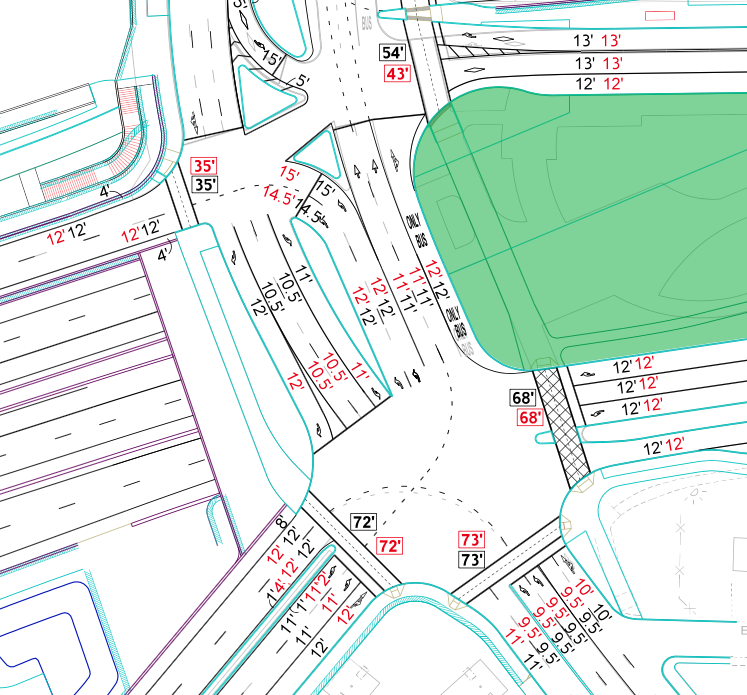

Another example is the nine-lane design for the Montlake Boulevard overpass of SR-520, part of the “West Approach Bridge North” project of the $4.65 billion plan to replace and upgrade the SR-520 pontoon bridge across Lake Washington. True, the project has a small bike facility but the vast majority of space is dedicated to car movement and storage.

Of course, STEB’s absurdity goes well beyond the headline. This passage encapsulates their asinine hypothesis and fairytale alternative:

Because Seattle straddles state freeways at their busiest points, it should be ready to absorb the traffic when they’re disrupted.

For instance, more traffic police were needed at key intersections far from Monday’s accident. Perhaps the 1,239 new city employees Murray has hired could be cross-trained to provide emergency traffic control.

Major incidents will keep happening, and their effects are worsened because Seattle eliminated numerous arterial lanes in recent years. This reduced capacity hurt on Monday.

Lanes were replaced with bicycle paths. The problem isn’t adding bike paths, it’s that the city did so by reducing general traffic capacity. This makes the street network less resilient and capable of handling surges — and more dependent on I-5.

Murray should consider the network’s brittleness as he prepares to reconfigure downtown streets. His One Center City plan will likely eliminate more general-purpose lanes, cutting arterial capacity adjacent to I-5. A potpourri of new bike lanes, streetcars and bus lanes are being considered on First, Second, Third, Fourth and Fifth avenues. Meanwhile the viaduct is being replaced with a smaller-capacity tunnel.

Obviously, STEB does not consider other modes in transportation resiliency. Nonetheless, transit lanes and bicycle lanes can carry many more people with less space. This isn’t ideology but rather geometry. By the way, assuming transportation policy be entirely centered around single occupant vehicles is an ideology all its own, even if it’s the default in some minds. Whether opportunistic trolling or a real policy proposal, cross-training new City employees to provide “emergency traffic control” happens to be illegal under City ordinance that stipulates only uniformed police officer do traffic flagging at intersections.

The Center City Connector streetcar project STEB derides while lamenting the loss of First Avenue car capacity is expected to allow Seattle’s streetcar system to reach daily ridership of 35,000 by 2035. That’s serious capacity for just one travel lane each direction, but high capacity transit makes it possible. Thus, transit lanes actually make our transportation system more resilient by fitting more commuters in less space.

The Third Avenue’s bus-only (during peak) lanes–which STEB decries for lost general purpose capacity–allows that street to carry daily bus ridership of 125,000 by Seattle Transit Blog estimation. Trading four lanes of capacity during peak hours so transit can more efficiently move 125,000 trips seems more than a fair trade. And, by the way, any transit rider could attest that Seattle Police Department doesn’t enforce the bus-only lanes very vigorously–plenty of motorist scofflaws sneak in left turns selfishly holding up buses.

Sound Transit estimates the ST2 package–which STEB opposed–will allow its light rail network’s daily ridership to surpass 300,000, while ST3–which STEB also opposed ad nauseum–would push it to about 600,000, according to projections. Talk about resiliency! Can you imagine if all those future trips switched to the single occupant vehicle mode–or even carpools or taxis? Can STEB really claim to care about transportation capacity when they opposed ST2 and ST3?

Bike lanes make an easy target and STEB has relished scapegoating them, but in actuality they rarely reduce throughput for cars. As Seattle Bike Blog pointed out, the only protected bike lane to replace a general purpose lane was Second Avenue, which was completed in 2014 and supported by STEB at the time–confounding in retrospect. Moreover, under Mayor Murray few additional protected bike lanes have been completed as the Bike Master Plan and Center City Network have been considerably delayed. And while STEB is correct acknowledging bike commuting is basically flat, that’s not because bike lanes have been consuming general purpose lanes left and right–they haven’t–but because the “potpourri” of bike facilities Seattle has do not really connect with one another. The rollout of protected bike lanes has been too slow and haphazard, not too fast, which is why cycling commute share hasn’t improved.

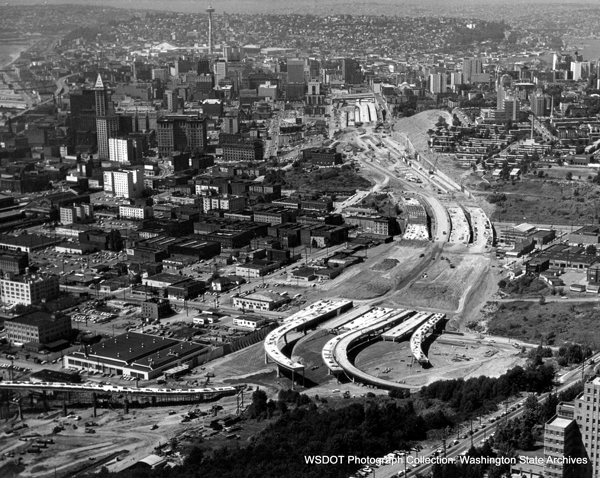

And lest we think Seattle hasn’t sacrificed enough for freeway capacity, let’s not forget that I-5 only exists in the first place because Seattle consented to demolishing 4,500 parcels that were the home of tens of thousands of its citizens to plow the freeway through its central neighborhoods. The pictures above show the destruction I-5’s construction wrought. I came to the opposite conclusion of STEB; more urban highways and freeways aren’t a good investment and we should not tear apart any more Seattle neighborhoods to create more. In fact, why not remove I-5–a finicky, collision-prone, destructive, disruptive, pollution-belching freeway–from our center city? It’s one rollover–whether the truck carries propane, salmon, or bees–away from being rendered useless anyway.

Related Article

Monday’s Traffic Meltdown Showed Downtown Freeways are Brittle

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.