“The solution: Americans, together and all at once, would have to stop thinking about their homes as an investment,” Conor Dougherty wrote in The Upshot this past Friday, which is an intriguing proposition others have echoed.

Implementing policies that furthers housing as a necessity rather than an investment is a good idea. But unfortunately that reframing isn’t in itself sufficient to solve the problem. How we arrive at the conclusion is important, because it also informs which policies we emphasize. Dougherty relies heavily on research by Ed Glaeser to make the case, and Glaeser’s research raises some question marks and perhaps red flags.

“According [to Glaeser] a standard American home should cost around $200,000, a figure that includes the cost of construction, what land would cost in a lightly regulated market, and a modest profit for developers,” Dougherty said.

Glaeser would have us believe all we have to do is get rid of zoning regulations and streamline permitting and then the market would work towards this idealized $200,000 cost of housing, no matter what on the market. This simplistic assertion betrays how markets work, particularly housing markets. If building costs and land costs dropped dramatically, developers may charge less for housing but there’s no guarantee they’d seek only a “modest profit.” It’s capitalism we’re talking about. Cities should urbanize their zoning, but let’s not promise miracles.

Eliminating land use controls is unlikely to turn San Francisco ballooned-out $800,000 median housing prices down to the $281,000 equilibrium Glaeser has somehow divined a deregulated market would support in San Francisco. The reason is simple: producers will charge what the market will bear; San Francisco’s market will bear a lot. Median housing prices track closely with median wages, and San Francisco median household incomes are very high–$81,294 by the Census Bureau‘s most recent count. That means even if San Francisco housing prices magically stabilized at what its median household could comfortably afford (30% of income with a 20% down payment), homes would still list at around $440,000.

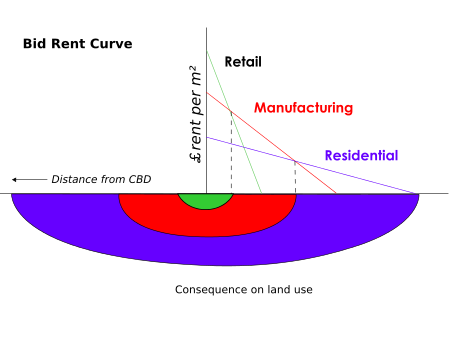

The Bid Rent Curve Helps Explain Soaring Prices In Urban Centers

Beyond demand playing a big role in setting prices, Glaeser’s studies fails to account for the location premium buyers are willing to pay. Prices have spiked in big city centers in large part because of this emphasis on location and urban amenties a new generation of homesbuyers is making. Don’t believe the peak millennial hype.

The Urbanist has covered how bid-rent curves better represent housing markets than simple supply demand graphs. It’s a fancy economic term but it reflects some simple truths: housing markets are local. They interact strongly with proximity to jobs. Prices are highest in the central business district (CBD) where jobs are concentrated and retail, office, industrial, and residential uses all compete for limited space.

Houston–the poster child for lightly regulated zoning that Glaeser has held up as exemplar–has 639 square miles within city limits while San Francisco has just shy of 47 square miles. That means more of San Francisco lies within the high-priced bulls eye of the bid-rent curve whereas Houston includes large tracts of real estate well outside it. Additionally, geography can have a big impact. San Francisco sits at the tip of a long peninsula in a mountainous region whereas Houston sits on a broad coastal plain. Houston’s growth could spill out in all directions, but San Francisco could only grow contiguously to the south or by jumping across the Golden Gate Bridge or the Bay Bridge. Thus, it’s hard to compare San Francisco to Houston without controlling for those fundamental differences.

For his part, Dougherty glossed over this idea and overlooked that not all land is equal. Some parcels are unlikely to sprout dense urban neighborhoods any time soon:

Housing is particularly prone to bubbles because, in contrast with other products, we seem to want it more when it is expensive and less when it is cheap. And no matter how many times we look out an airplane window to see vast acres of emptiness, we somehow still believe that land is a great investment because nobody is making more of it.

In practice, farmland or wilderness is most likely to be developed as suburban sprawl. Many miles from downtown, these greenfield lots’ primary attraction is to host McMansion subdivisions with big lawns and three-car garages, not urban style neighborhoods. And because we are more than 70 years into the automobile-based suburban sprawl, much of the empty space that is within easy commuting distance of a central business district has already been consumed. Expanding high capacity transit lines into “emptier” areas can help urban development branch out, but it’s a risky public investment and ultimately older neighborhoods that grew around former streetcar lines often end up remaining the higher demand areas.

Land Values Reflect Current Use And Zoned Capacity

The suburban sprawl that rings urban cores can impede urban growth and cause housing costs to rise. We’ve squandered many of our greenfield development opportunities generations ago with low-density uses. Infill development is simple enough where vacant lots or depleted stock can be turned over in otherwise urban neighborhoods. But it’s harder for infill to take hold in suburbs without good “bones” for urban development. Dense mixed use buildings don’t work well with cul-de-sacs and curvy collectors. Plus, in a booming metropolitan area, suburban blocks that might be suitable for urban redevelopment often already have considerable value as detached homes, not to mention current inhabitants who would need to be willing to sell for that redevelopment to happen.

Cities that upzone single-family residential zones may see them redevelop over time and gradually urbanize suburban sprawl. Urban development still typically follows frequent transit lines with a reasonable commute to downtown and gravitates toward places with good amenities: parks, high-performing schools, vibrant commercial districts, and scenic views. And conversely, perception that an area is high crime can stunt redevelopment, even if that perception is more rooted in racial stereotypes than hard data. In sum total, this means urbanization isn’t likely to happen just anywhere.

When we’re talking about densifying already urban areas, the picture gets even more complicated. San Francisco’s density is already more than 18,000 people per square mile. Essentially that means more land is already being put to relatively high value uses. Instead of big lot detached homes or parking lots, more development will have to replace rowhouses or smaller apartment buildings that are pretty valuable in existing use. The higher level of improvements on the land makes it hard for redevelopment projects to pencil on top of it since buying out existing uses adds cost.

Other Reasons To Urbanize Zoning

Overly simplistic theories can be seductive, but there’s nothing simple about rapid urban growth in an area hemmed in by extensive suburban sprawl. We should urbanize zoning–more lowrise multi-family residential zoning in many more places, mid-rise near high capacity transit, and high-rise zoning near light rail stations–because we don’t have many other ways to meet demand when suburban sprawl has already consumed most readily available land between Everett and Tacoma. And unlike suburban sprawl, urban development is much more likely to financially support itself rather than working like a Ponzi scheme. This is very important to the long-term health of our communities and the local government bodies that service them.

To individual tenants and homebuyers, urban zoning also boosts local amenities, even for the folks who continue to live in single-family homes. Commercial districts grow and thrive around mixed use buildings adding more choices in restaurants, cafes, groceries, shopping, and services. The lack of those things within walking distance is part of what’s oppressive about suburban living. The new storefronts provide opportunities for local entrepreneurs to launch or grow their business enterprises.

Expanding commercial opportunities overlaps with cities mission to be sanctuaries and cultural tapestries. Studies have shown immigrants are integral to founding new businesses. Immigrant entrepreneurs launched 28.5% of all new American businesses in 2014, according to an Ewing Marion Kaufman Foundation analysis. In Seattle we have declared ourselves a sanctuary city for immigrants, but we have to ensure refugees we shelter have economic opportunities, too, not just tough words. And obviously being a true sanctuary city means having affordable housing. Vibrant commercial districts and moderately priced housing point toward mixed use neighborhoods with apartments and modest-sized homes. Launching a new business can be tougher in sterile suburbs dominated by big box stores and chain restaurants with little in the way of foot traffic. Cities must be vehicles of economic diversity otherwise we will impoverish the cultural diversity we say we hold dear.

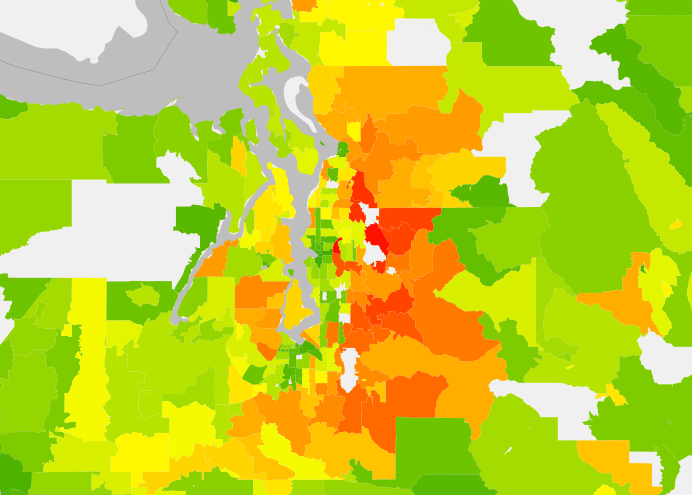

Finally, urbanizing is a necessary step to protect our environment and mitigating climate change. With a population of more than seven billion and billions more expected in coming decades, we can’t expect our suburban pattern of growth to function going forward. People living in suburbs, especially outer ring suburbs, have a comparatively large carbon footprint generally speaking, as carbon footprint maps attest. The transportation carbon footprint of an urban household with one car could be as many as five times smaller than a suburban three-car household. It’s possible to triage these unsustainable growth patterns. The infusion of density upzoning can provide make neighborhoods more attractive candidates for transit upgrades, leading to a virtuous cycle that decreases neighborhoods’ respective carbon footprints. And building with mass timber technologies like cross-laminated timber can help cities sequester carbon in our buildings while providing high quality spaces and boosting the local timber industry.

Many reasons exist to urbanize, from the big picture–it’s the healthiest way for our planet to grow–to the more immediate boon of invigorating neighborhoods with more people, businesses, and amenities. To lower the cost of housing, we have to use all the tools in the toolbox from public housing to inclusionary zoning to community land trusts to pro-urban-growth policies. If we want housing to not be treated as primarily an investment any more, community land trusts literally do that, as does government or non-profit ownership. Cutting in third the price of housing probably isn’t a reasonable expectation and housing deregulation would come with harmful side effects anyway. It’s hard to get housing prices to swing dramatically in the short-term, and the bid-rent curve suggests housing in urban cores will remain desirable and expensive relatively to comparable housing out in suburbia. Building more will certainly moderate prices, and done smartly it will lower displacement, as the best evidence shows. We have to keep chipping away at the urban project because it puts our region on a more sustainable course that will pay dividends for many years to come.

A thought experiment: What would happen if we all stopped thinking of our homes as investments? https://t.co/ruBuxkc6My pic.twitter.com/V3iNbObRrU

— The Upshot (@UpshotNYT) February 13, 2017

Why Seattle Needs Inclusionary Zoning, Explained By The Bid-Rent Curve

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.