Last week we outlined the different proposals to address the “congestion” crisis that our transportation agencies, in conjunction with the Downtown Seattle Association, are trying to prepare for in September of next year. That is the date of the King County Metro service change that will bring all Downtown Seattle Transit Tunnel-running buses onto surface streets so that Convention Place Station can begin to be decommissioned on its way to becoming the site of the next phase of the Washington State Convention Center’s expansion.

That plan is called One Center City and the advisory group, made up of approximately 40 citizens representing different Downtown interests, saw those recommendations at the very same time that they were sent to members of the press and by extension the public. At this point we do not know how the advisory group will respond to those recommendations as a bloc, and what options might be on the table outside of the ones we have seen so far.

One thing is clear, however: right now safety looks like it’s an afterthought on almost all of them. Which is particularly strange considering the high profile focus on Vision Zero since the launch of Seattle’s campaign, and with the speed limit changes focusing on Downtown streets. For a mobility plan that could invest tens of millions of dollars into our center city streets, how could safety become so easily forgotten?

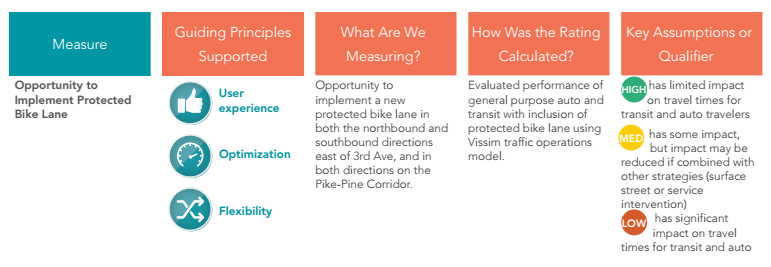

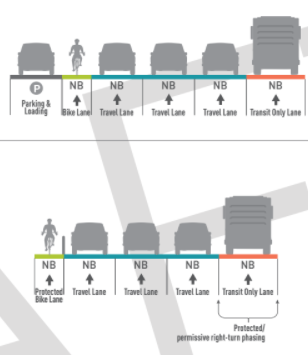

To illustrate how the plan sidesteps Vision Zero, look no further than the different bike lane proposals in the concepts outlined. Before the proposals are identified, the end-level results are identified (what do we want?) and the guiding principles that those outcomes support are picked out to support. The guiding principle that explicitly tracks to safety is “equity”: “Design for the health, safety and well-being of all who live in our community using established race and social justice guidelines.”

The opportunity to implement a protected bike lane does not support Stewardship, Public Space, or Equity?

It’s important to stop here and note that while having a direct impact on increasing the level of safety for current bike users, increasing the number of bike users overall, protected bike lanes have a comprehensive effect on the street-level environment. They almost always slow vehicle top speeds down when street space is reallocated, and they frequently come with signal improvements that benefit pedestrians as well–look at the Second Avenue bike lane as an example. To leave those guiding principles off for bike lanes is to either not be paying attention or to have a very narrow view of what bike lanes can do for downtown environments.

Meanwhile, general purpose travel time supports equity and stewardship, for some reason.

The spelled-out definition of stewardship in the very document itself is to “reduce vehicles and emissions and use sustainable building practices.” Something is broken here.

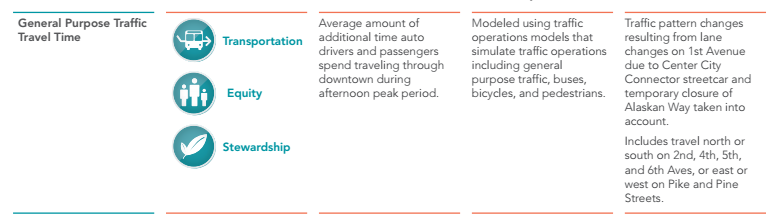

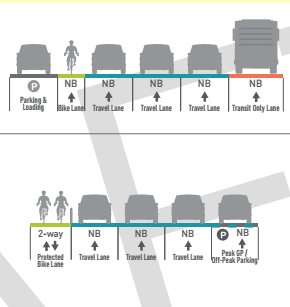

Looking at the proposals themselves, two of the three concepts for north-south streets include protected bike lanes east of Second Avenue. Option B proposes a couplet utilizing Fourth and Fifth Avenues–this could alleviate some of the confusion that seems to abound around Broadway and Second Avenue turning traffic–and option D proposes a two-way cycletrack on Fourth Avenue. Debating which one is better for cyclists and Downtown visitors is exactly what the advisory group was created for. Only option C eliminated any proposed bike lanes outside of what is currently on the table for central Downtown. Let’s assume for the moment that we are safe from that extreme proposal.

Every Downtown cyclist knows that north-south routes are not the main problem with Downtown travel: east-west is the issue. I did not address the east-west proposals last week when running through the north-south options for two reasons: the transit aspect is clearly secondary on the east west corridors in the proposal, and the ideas so clearly demonstrate the disconnect on Vision Zero that it is impossible to separate the two.

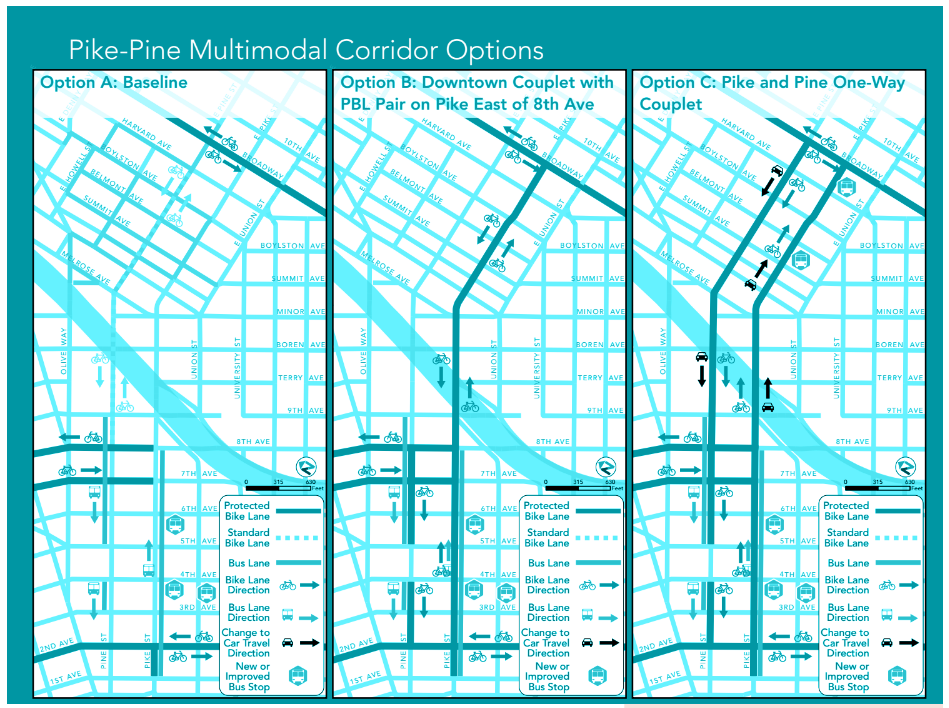

The proposal lays out two possibilities for east-west bike lanes between Downtown and Capitol Hill. Both Pike and Pine have bus lanes now in Downtown that disappear around the freeway. No concept proposes extending those, so it’s just bike lanes, general purpose lanes, and parking lanes that are jostling for space here.

Option B proposes one-way bike lanes downtown, following the direction of car traffic on both Pike and Pine Street, connecting to the couplet in planning right now for Seventh and Eighth Avenues. A two-way cycletrack on Capitol Hill on Pike Street would connect Broadway to that Downtown couplet at Eighth Avenue.

Pretty simple, though my sense from talking to business owners and people beginning outreach on Pike/Pine bike lanes in Capitol Hill is that the Broadway cycle track has many business owners opposed to another two-way cycletrack on the Hill. A couplet could be more palatable, which brings us Option C.

Option C continues the Downtown couplet all the way up to Broadway. But it also proposes turning Pike and Pine in Capitol Hill into one-way streets so that all traffic is traveling in the same direction and so that parking spaces can be conserved. Option B would require conversion of 78 parking stalls away from parking into a travel lane of some sort, and option C would only require converting 30.

But the essential question to ask is: would the conversion of those streets from two-way to one-way have an impact on pedestrian and cyclist safety for users there? It’s not hard to find the answer. Pike and Pine are unsignalized from Harvard Avenue to Bellevue Avenue. Creating two lanes heading the same direction from one would almost certainly lead to vehicles creating a wall of traffic that intimidates pedestrians and encourages failure to yield. Venture into any neighborhood with a multi-lane one-way street without signals, like Second Avenue in Belltown, and try and cross the street.

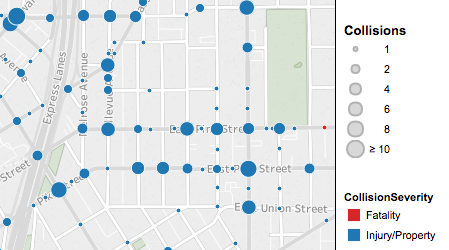

Compound that fact with the remarkable number of collisions that occur at the intersections in question as they are now. The map below uses collision data from the Seattle Department of Transportation, collected between 2007 and 2014. Both Bellevue and Boylston at Pine saw six collisions during that period, and Summit and Harvard at Pike as well as Belmont at Pine saw five: unacceptable numbers for a city trying to get to zero serious injuries.

The one-way conversion should not be on the table at this point. It does not take a safety-first approach to the mobility needs of our city. It prioritizes parking retention and minuscule gains in general travel time over those needs.

The good news is, the advisory group does appear to be ready to pick up that baton after it was so recklessly dropped by the agency partners. Several advisory group members I have spoken with have confirmed that the group took pains to specifically insert safety into every single guiding principle and has no intention of letting other needs take priority. How much weight the advisory group’s decisions will be given, however, remains an open question at this point. It is important to note that the proposals presented last month have been kicking around at the partner agencies for quite some time, and the public input process now is the first time that both the general public and the advisory board will really get to have an influence on what stays on the table.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.