Note: the article below separates transit proposals in the One Center City recommendations from the bike lane proposals. I am devoting an entire article next week to the issue over bike lanes and Vision Zero in the One Center City plan. Therefore, I have not discussed the bike lane aspects of any of the proposals below. Stay tuned for more analysis on all aspects of the proposal to come.

Last week, we got our first look at what recommendations are under consideration in the multilateral Downtown mobility project known as One Center City. In advance of the fifth meeting of the One Center City advisory group, a 35-page set of options on how to keep Downtown moving was presented to members of the press, before the advisory group even had a chance to review them itself. The presentation was made on behalf of the four main partner organizations involved in One Center city: the Seattle Department of Transportation, King County Metro, and Sound Transit (the three major public agencies that are involved in transportation decisions Downtown) as well as the Downtown Seattle Association, a private non-profit mainly focused on economic development Downtown.

The recommendations are the first attempt at the reshuffling of Downtown street space to accommodate several big changes coming to Downtown in the next few years as Seattle continues to grow. The biggest of these is the exit of bus routes from the Downtown Seattle Transit Tunnel in favor of dedicated rail there: the buses that light rail won’t replace will need to find a place on the surface, already packed with buses during peak hours. The development of the expansion of the Washington State Convention Center across Pine Street is requiring buses exit the tunnel earlier than they might have otherwise.

With buses like the 41 (express to Northgate) and the 550 (express to Bellevue) needing to occupy Downtown streets until 2021 and 2023 (respectively), what is pretty clear is that someone is going to have to give up street space. In this first set of draft recommendations, it is pretty clear that users of private vehicles are not going to have to do so.

It is important to note that the restructure proposals are not all-or-nothing and that we will likely end up with a mix of the proposals outlined below, as well as the fact that all of these ideas are still in draft form.

Heavy Truncation of Routes

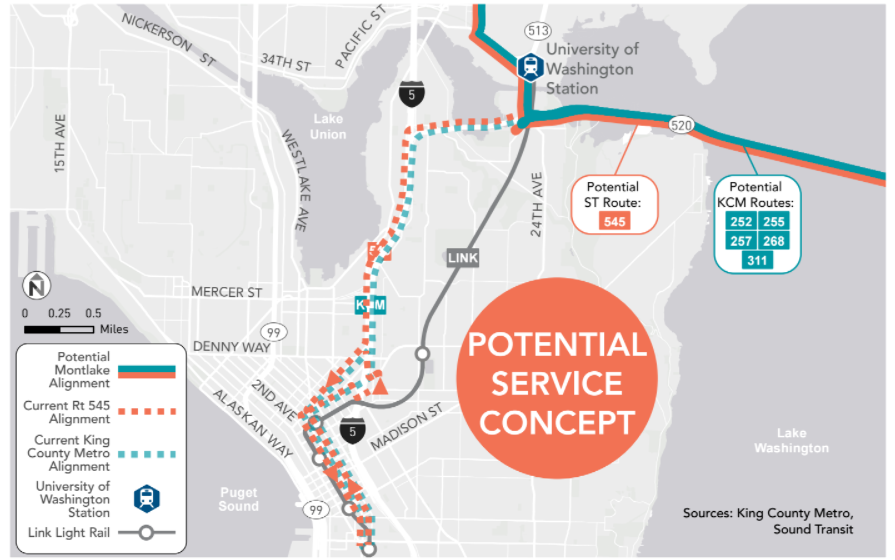

The plan proposes terminating all SR-520-based routes (Sound Transit 545 and Metro 252, 255, 257, 268, and 311) at the University of Washington Station and not having them serve Downtown at all. This would require a $3 million investment in the Montlake Triangle area to create more bus capacity. According to the document, transferring riders at UW Station would offer no change in travel times from current trips for riders going to Westlake or International District stations, and that construction impacts, both from the convention center and the Portage Bay bridge replacement, would add five minutes of travel time to every trip between the Eastside and the International District.

It is unclear what the impact would be to SR-520 riders who live or work in areas not served well by Link, including the large contingent of riders who take the 545 from lower Capitol Hill during the weekday morning peak. Would Microsoft’s Connector service need to be expanded to meet increased demand and what impact would that have on Downtown streets as a counter-impact?

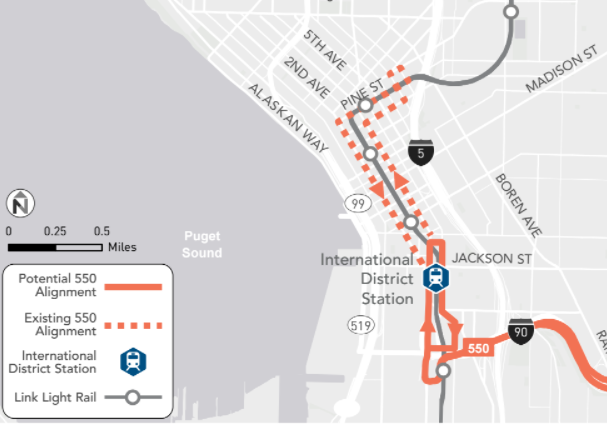

It also proposes truncating the 550 at the International District station, which also would need up to $2.5 million in investment to accommodate extra buses and passenger waiting areas. This change obviously offers no travel time benefit for riders at International District. According to the document, if the buses were to continue to the vicinity of Westlake Station, it would add around three minutes to every trip compared to what it would take now.

Another set of routes they want to keep the heck out of Downtown are peak-hour West Seattle, Burien, and Vashon Island routes. These buses are already on Third Avenue, but would instead be routed via Pioneer Square up the new Yesler Way bridge to First Hill. It is unclear how much Third Avenue capacity could be achieved with the complete removal of private vehicles during peak hours or even increased enforcement of the current limited-access rules.

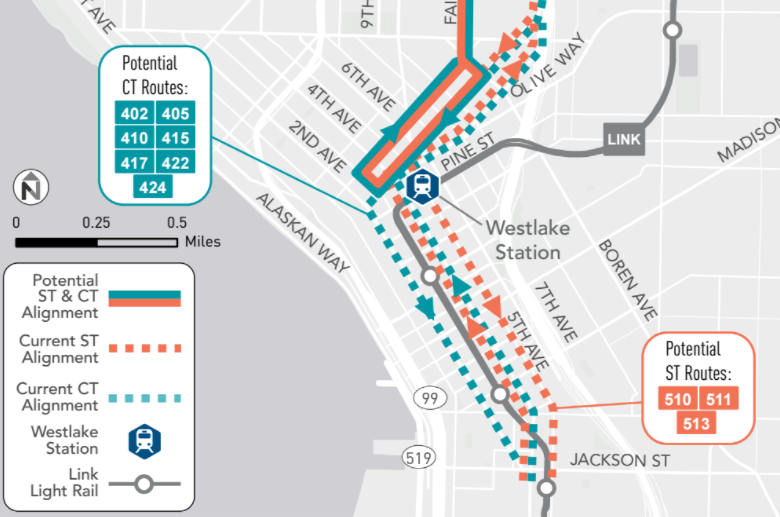

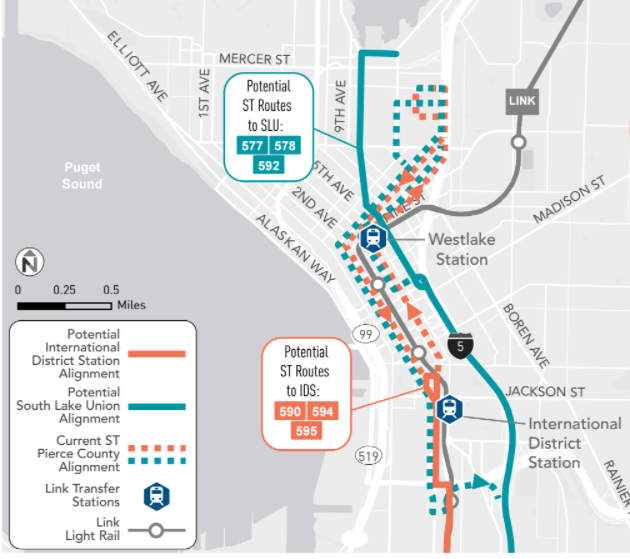

For Snohomish County riders, several peak-only Community Transit routes are proposed to change to only serve the International District station: the 412, 413, 416, 421, 425, and 435. Other Snohomish County routes would be switched to serve only South Lake Union and North Downtown, using Mercer Street to exit I-5 and Fairview Ave N to serve only as far into Downtown as Olive Way and Third Avenue.

For Pierce Transit routes, the proposal would route some bus routes to South Lake Union (577, 578, and 592) and some to International District (590, 594, 595).

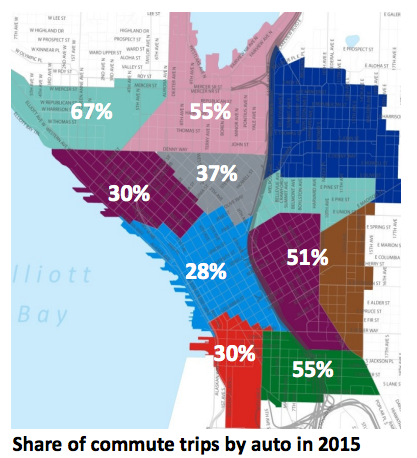

It is worth noting that South Lake Union has one of the highest drive-alone rates among our Downtown neighborhoods. Because it is not a neighborhood that is well served by Link, truncating riders at Link stations will clearly have a negative impact on transit ridership usage to South Lake Union, and other neighborhoods that would lose direct service, like parts of Belltown. While truncating routes sometimes makes sense, reducing direct service to growing center city neighborhoods because we are not able to give up precious street space in Downtown seems very shortsighted.

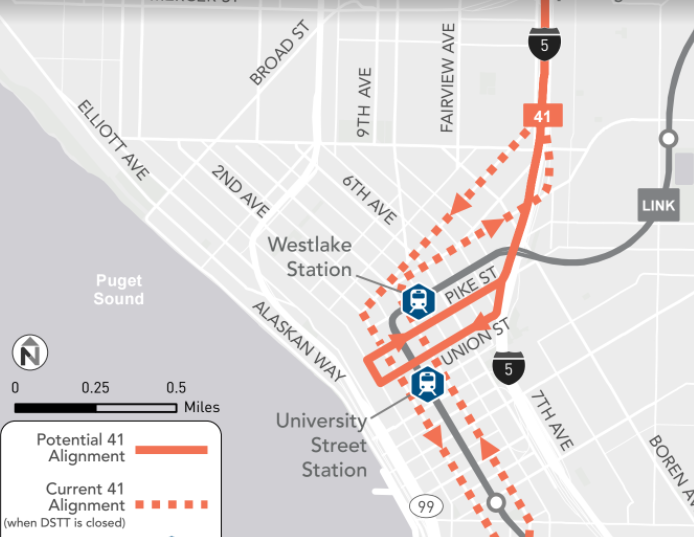

The route 41 is proposed to to change to serve only the northern portion of Downtown on a loop on Pike Street and Union Street (like the Sound Transit 522) until Northgate Station opens in 2021.

Changes Downtown

Even with scaling back the number of bus routes that travel through the heart of Downtown as outlined above, street changes are still going to be required there to keep travel times competitive for riders and to maintain capacity as Downtown construction projects all converge at the same time. The choice right now is: are we going to decide to invest a heavy amount of money into capital improvements for our Downtown streets in order to save money on operating costs, or are we going to make minimal investments in our infrastructure and instead leech operational funds as our buses sit in an increasingly congested Downtown core? Clearly, the answer is somewhere on that spectrum. There are four options being considered.

Option A is do nothing (which would cost up to $8 million in additional operating costs per year and is the entire reason this study is occurring, so we won’t spend any time on it, except to say that doing nothing would be expected to add an average of 3.5 minutes of travel time to every Downtown bus during peak hours).

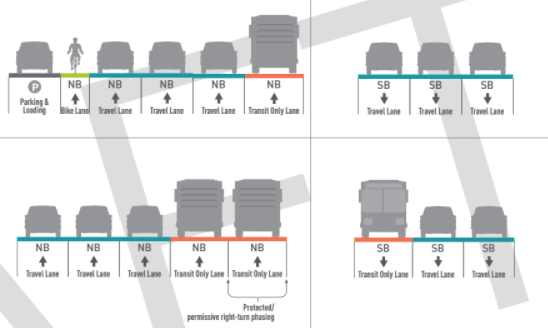

Option B would improve signals on Second Avenue and Fourth Avenue, which already has transit lanes. Adjusting signals to allow turning vehicles to exit the transit lane more quickly is the main operational advantage of this plan. It would also expand off-board payment on Third Avenue (currently limited to RapidRide buses) to allow more buses to use the corridor as dwell time decreases. The investment cost of this plan is estimated at $11-$15 million and would bring the annual cost to transit operating costs to less than $2.5 million from the $8 million mentioned previously. Because this plan essentially maintains the same amount of lanes devoted to transit, travel times for private vehicles in this plan are improved from the “do nothing” plan.

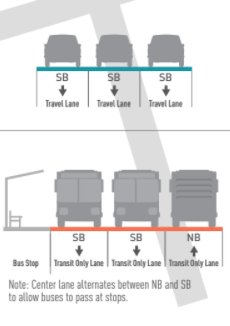

Option C adds an additional transit lane to Fourth Avenue and a new transit lane on Fifth Avenue. With these streets being one ways, this creates a transit couplet. More buses would move to Fifth Avenue, and the two lanes on Fourth Avenue would allow buses to both leapfrog each other and turning vehicles improving reliability. Option C is supposedly dependent on turning Sixth Avenue–currently one-way–into a two-way street between Stewart and Marion to alleviate traffic getting to I-5. This plan would cost $14-17 million up front, and only cost $1 million per year in operational costs. The most on-street parking spaces are removed in this plan, with 45 parking spaces, 19 passenger load zones, and six commercial load zones co-opted by the additional transit lanes.

Option D turns Fifth Avenue into a transit street between Stewart to Jackson: bus-only during peak hours with limited access, just like on Third Avenue. The transit lane on Second and Fourth Avenues would turn general purpose, and, as in Option C, Sixth Avenue would turn into a two-way street. This is clearly the most drastic change proposed, and is very capital intensive. It is estimated to cost up to $28 million but would apparently prevent net transit operating costs from increasing. It would also have a very minimal impact on travel times for private vehicles, with only 0.7 minutes added to northbound traffic and 0 minutes added to southbound.

Not a Grand Bargain

The proposals that were identified all seem to be focused on maintaining minimal impacts to private vehicle users in downtown. Ironically, these truncation proposals for highly used express routes that serve our biggest employers might have the opposite intended effect, encouraging users to drive to work more, if the alternative becomes a transfer that is not competitive. It does not make sense that the largest number of commuters into Downtown, transit riders, should have to bear the brunt of impacts to our transportation system, when our stated goals as a city are to to reduce single occupancy vehicle mode share and to increase all other mode share. Rather than trying our hardest to maintain the status quo, we should be looking for innovative ways to move as many people as possible, particularly if it involves getting them out of their cars.

You can view an online open house on these options at the One Center City website.

Later this week we will look at other aspects in One Center City, including the proposed bike facility options as well as the east-west corridors proposed between Capitol Hill and downtown.

Title image credit: SounderBruce (Flickr)

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.