On Friday afternoon, staff at the Seattle Department of Transportation working on a plan to expand Seattle’s bikeshare program and make it successful had the rug pulled out from under them. In typical Murray Administration fashion, the news came at 5:00 pm, with the press release titled “City announces $3 million in bicycle and pedestrian improvements” that actually buried the lede: “The funding for these new projects is derived from funding previously allocated to the 2017 re-launch of the city’s bike share program”. Those $3 million in funds will now be diverted to other SDOT capital projects, particularly Safe Routes-to-Schools, a program that no reasonable person would ever object to.

The release also promises to use some of the money for Downtown bike infrastructure in the form of “completing a missing link of the 4th Avenue bicycle lane and extension to Vine Street” and “accelerating design and outreach for the east/west connections in the Center City bicycle network.” Side note: we have been accelerating design and outreach for east-west bike lanes Downtown since at least the second Bush Administration and it was a concept under discussion for decades before that.

The turn-on-a-dime announcement cloaked in the guise of investments to safe streets is a big blow to bikeshare in Seattle: the plan was to sell back the current bike stations and all their bikes and start over again, with a fresh approach. Seattle’s hills would be conquered with the help of an added feature: electric-assist on all bikes.

Why Pronto Failed

The question of why the first attempt at bikeshare in Seattle failed is important. Whatever the conventional wisdom says the reason was, that will solidify and turn into the main talking point whenever bikeshare is put back on the table. If the answer is hills, rain, the fact that people in Seattle just don’t bike, or the King County helmet law, then the inertia of the idea of those problems will be hard to overcome, because they aren’t likely to change anytime soon. Those are just some of the ideas that are floating around Internet comment boards and coffee shops this weekend after the Mayor’s announcement. And it’s clear that while some of those things may have played a part (particularly the helmet law, the others minimally) they were not the reason that Pronto did not meet its ridership goals and became prey to its own debt service, requiring a bailout.

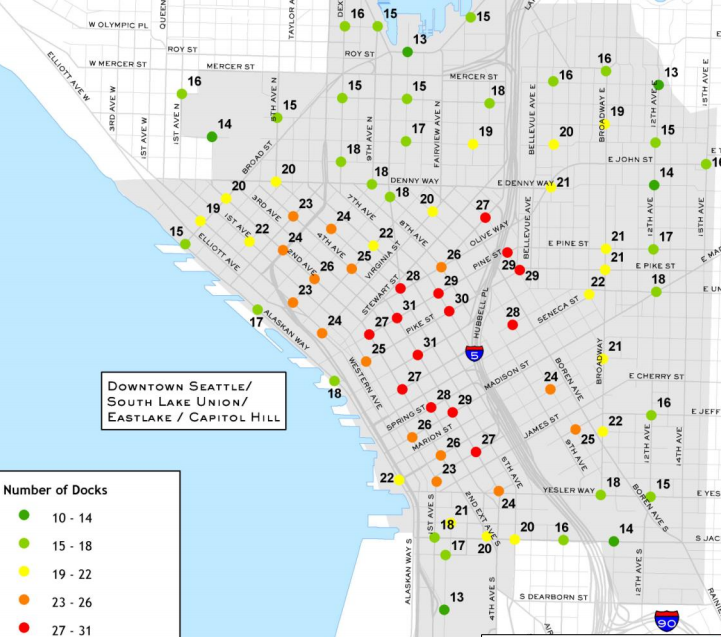

In 2012, Alta Planning, the company that became Motivate, the current operator of Pronto bikeshare, completed a study on the feasibility of launching a system in King County. They concluded that Phase I of the launch would focus on Downtown, Capitol Hill, and the University District: the neighborhoods that ended up getting stations during our initial rollout. A dense network in those neighborhoods was proposed, particularly Downtown. From the plans:

Average station spacing in European and North American bike share systems is typically between 984 feet (300 m) and 1,300 feet (400 m). This represents a station density of approximately 16 to 28 stations per square mile. This range provides access to a bike within a short walk of anywhere in the service area and provides a nearby alternative to return a bike if the destination station is full.

Contrast that with the system we have today: a whole segment connecting south Downtown with Capitol Hill is not present, and all of the stations are much further apart that they are in the plan.

The reason for that is that the 2012 plan laid out a two-part initial rollout, and Pronto never got around to its second part of Phase I. That phase would have filled in the gaps between stations, making the system much more attractive to casual users. In addition, because the rollout was expected to have a second phase, the first phase placed stations in a completely haphazard way, with the thinking that they would get moved around when the other stations were added.

In the initial plan, stations were placed over Downtown in a grid. Then they were moved around, with the following criteria in mind:

1. If there was a major transit station nearby (e.g. a light rail station or ferry terminal) then the bike share station was moved to that location.

2. Where there was no major transit station nearby, stations were moved to the most “exposed” street intersection. Exposure was measured using street functional classification to represent passing pedestrians who might use the bike share system and passing motorists that would see sponsorship at the station or on the bikes.

3. Preference was given to streets with existing or proposed bikeway improvements to represent the readiness of these streets to accommodate bike share traffic.

–Alta Planning documents, 2012

And it appears from where stations are today that essentially the same thing happened in real life. None of those criteria were clearly followed in the initial launch. There are no stations on the same block as a Link station Downtown. Some stations are on the other side of the street from the bike facilities close by, and some are tucked away on blocks where few cyclists would find them.

In short, bikeshare in Seattle was never really given a chance to be successful.

The Financial Model of Bikeshare

An issue that is becoming conflated in this debate over reallocating funds from bikeshare into capital projects within SDOT is the issue of capital costs versus operating costs. During budget negotiations late last year, the Seattle City Council slashed the operating budget for Pronto in half, saving around $30,000 for the budget cycle. That put an end date on how long Pronto had to operate, forcing them to cease operations by the end of March. Saving money on operating costs, however relatively small the amount, is a perfectly reasonable decision for the Council to make with a system that is atrophying riders because the system is not expanding.

But the Council had already allocated funds for expanding the system, $5 million. $1.4 million of that went to purchasing the assets for Pronto, in March, after the system would have shut down due to being too debt-burdened. However, much of that money could be recouped when the bikes were resold, that money reinvested in the new system. So while the City has spent a considerable amount of money in operating costs, the capital investment that the Council originally earmarked was still on the table to create a full-scale, workable bikeshare system.

In most cities where the bikeshare system is owned by the city or municipal government, operating costs are entirely covered by revenue from memberships and daily users, and by sponsorship. In most successful models, those funds are actually more than enough to cover operating expenses and the surplus is used to reinvest in the system, expanding it, and therefore creating a positive feedback loop.

Investing $3 million in Safe Routes-to-Schools is a great investment. However, it cannot be argued in any way that by doing so we will get that money back and then some. With bikeshare, that argument can be made. Officials at SDOT working on bikeshare made it clear in public meetings on the topic that they know what a successful model looks like and how to make it work. It appears that the Mayor and several members of the City Council do not have confidence in them.

Bikeshare’s Last Stand?

The death of bikeshare in Seattle is being framed by the Mayor as a win for people who walk and bike. “While I remain optimistic about the future of bike share in Seattle, today we are focusing on a set of existing projects that will help build a safe, world-class bicycle and pedestrian network,” the press release on Friday read. Given the terrible publicity that Pronto has received over the past year, it is hard to imagine how well-placed that optimism is. There will always be capital projects to fund: SDOT’s maintenance backlog is close to a billion dollars and growing. There will always be sidewalks to construct: Move Seattle funds almost none of Seattle’s missing sidewalks. There will always be reasons to say “no” to bikeshare, and many of those reasons will be the same ones that were used by the Mayor’s office on Friday. Doing so means that we lose one more tool in our toolbelt for mobility in our city.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.