Seattle has an immense amount of transportation assets. The total value is estimated to be over $20 billion, which the City’s transportation department (SDOT) documented in a 2015 asset management report. SDOT owns and maintains a broad spectrum of physical assets, including things like:

- Signals and street signs;

- Sidewalk receptacles and benches;

- Streetcar rails, rolling stock, and other transit facilities;

- Parking meters and bike racks; and

- Bridges, roads, bike lanes, and sidewalks.

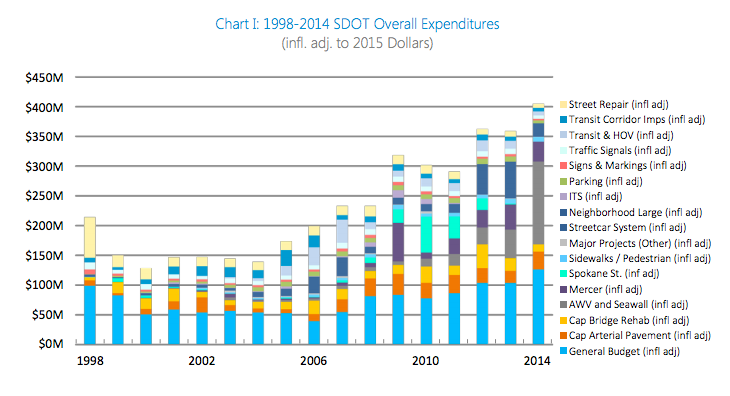

The cost to maintain these assets has generally been growing since the late 1990s, in part due to increased investment in existing and new infrastructure. Annual expenditures on transportation infrastructure exceeded $400 million in 2015. Depending upon how you slice it, the 2017 budget pegs more than $450 million for transportation expenditures over the coming year with another some $570+ million in 2018. Some of the big ticket investments in recent years have been projects like the streetcar system, Mercer Street realignment, seawall replacement, and Spokane Street repair and expansion. Other transportation categories, like pedestrian and transit facilities, have also seen increased investment compared to other asset classes.

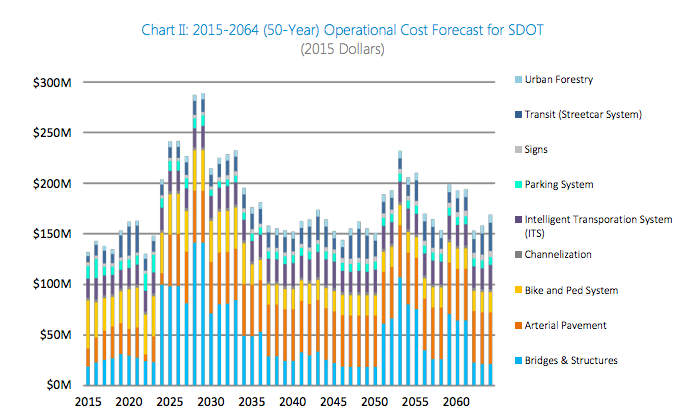

As some of these projects reach completion, their itemized impact on annual expenditures will decline and fall into ongoing operational costs bucket. To plan for ongoing maintenance, repair, and replacement of facilities, SDOT has developed a long-term forecast on operational expenditures for the City’s transportation assets through 2064. The forecast doesn’t count minor asset classes, certain traffic safety devices, and real property, but it does account for the cost of most other types of physical transportation assets.

Notable in the chart above is that operational costs will spike in the mid-2020s and last through the mid-2030s, and then again in the middle of the century. The SDOT report explains why this is likely to occur:

…[F]unding needs peak in the late 2020s and again the 2050s. These peaks correspond roughly to 100-year return cycles for replacing bridges constructed during building booms occurring in the 1920s and 1950s. The peak in the late 2020s also assumes that we replace the North Seawall during this period at a cost of $350M (2015 dollars). Other major assumptions include minimal spending for non-arterial pavement, $51M/yr. spending on arterial pavement starting in 2025 (to sustain existing pavement quality), physical elimination of pay stations in 2030 (leading to a commensurate drop in operational cost), a 33-year traffic signal replacement cycle, 100-year replacement cycles for existing areaway street walls and retaining walls, modest increases in urban forestry operational costs over time, and construction of the Center City Connector Streetcar in 2020-21. Full replacement of the Magnolia Bridge is not included in the cost forecast. Specific asset-based future operational cost forecasts are included in each subsequent chapter of this report.

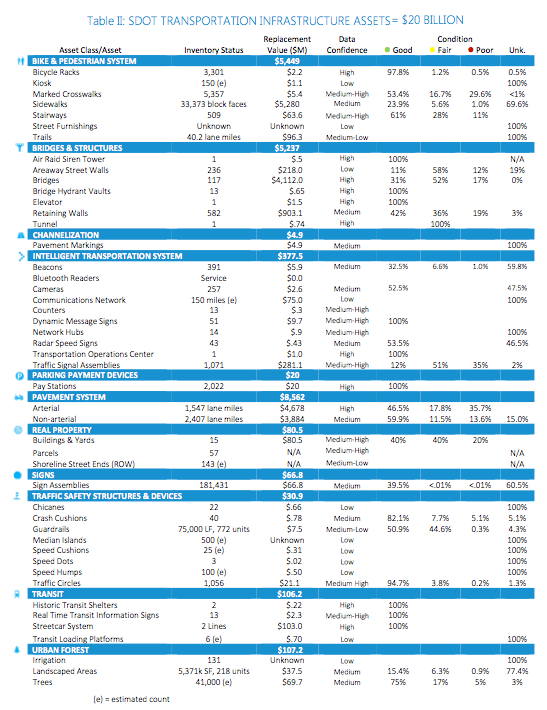

The SDOT report categorizes transportation assets by class ranging from bike and pedestrian facilities to road types and Intelligent Transportation System (ITS) features. A table in the report summarizes these by providing information about how much of each asset type is held by SDOT, the corresponding replacement value, and the condition of the assets.

Perhaps surprisingly, the asset table has a lot of unknowns with regards to conditions of landscaping, many street safety devices, and trails. Yet assets like air raid sirens, historic transit shelters, and guardrails are known in great detail. If nothing else, those insights into data gaps will likely will help agency staff identify areas where to put additional effort into collecting asset management data to better maintain them.

The table also tells a lot about how the City has invested into an asset class. At a high level, we know that there are more than 1,500 lane miles of arterials valued at $4.678 billion and another 2,407 lane miles of non-arterials that are collectively worth $3.884 billion. Together, those assets account for $8.562 billion of the $20 billion transportation network owned by Seattle.

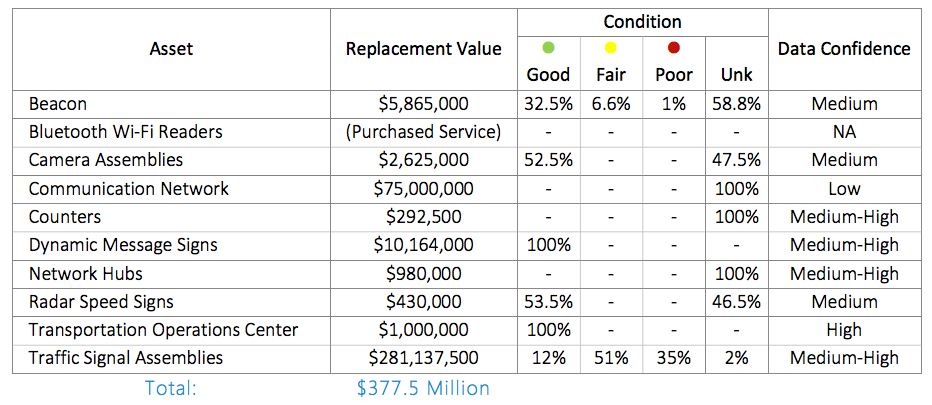

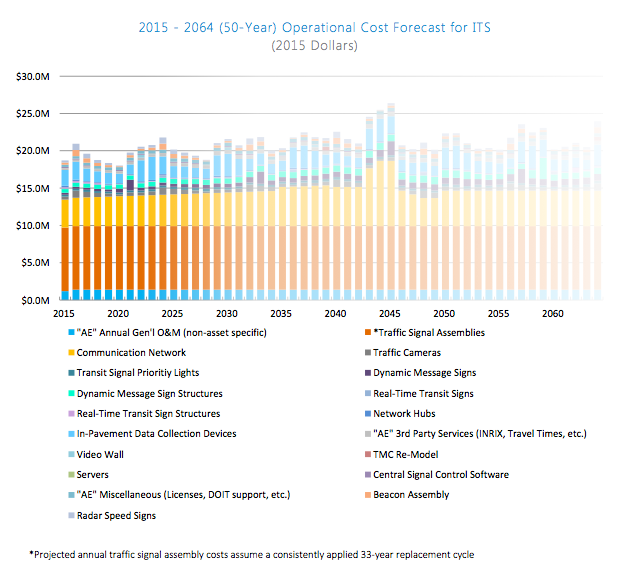

Digging deeper into the report, it’s possible to drill down into sub-classes of assets. Take the ITS assets, for instance, where SDOT categorizes the sub-assets as things like beacons, radar speed signs, counters, communications, and traffic signals. In total, the assets for ITS would cost $377.5 million to replace in today’s dollars.

Over the next 50 years or so, the ongoing maintenance of the ITS network is largely anticipated to remain the same from year-to-year, with only a few peaks and valleys for costs.

But it’s possible to see this for each of the other asset classes as well.

Seattle has a lot of transportation needs that have long been unmet (e.g., missing sidewalks, deteriorating bridges and pavement, and safety improvements), but this list will only continue to grow in the years ahead as the City tries to play catch-up between existing needs and new demands brought on by added growth. Indeed, new development will serve to provide some localized benefits through frontage and on-site and off-site improvements, and the City’s ongoing capital programs and Move Seattle Levy will help get at the backlog. But aging infrastructure and growing operational costs from new infrastructure will continue to put a strain on outlays. Planning for maintaining the city’s $20 billion–and growing–transportation infrastructure is a good start at managing risk in the years ahead and programming investments.

City of Seattle – SDOT 2015 Asset Management Report by The Urbanist on Scribd