Las Vegas has often been viewed as an urbanist’s nightmare, a sprawling offence to nature. From a population of just 16,000 in 1940, it has grown to over 2 million people today, a more than hundred-fold growth in the driest major metropolitan area in the United States.

Fake waterfalls and lush foliage around the casinos of Las Vegas’s famed gambling strip mask a desert heart.

In the early 1990s, Las Vegas seemed headed for a crash, with some 50,000 new residents arriving each year and a water supply that appeared about to run out. But in the decades since, the Nevada metropolitan area has remade its water management institutions and reframed the community’s attitudes toward the scarce resource in a way that offers lessons for cities facing the challenges of resilience in the 21st century.

Resilience, as Brian Walker and David Salt describe it in their book Resilience Thinking, is the ability of a system to absorb a shock and retain its basic structure and function–to retain its core identity. For an ecosystem like a coral reef, the shock could be rising ocean temperatures. Once they pass a threshold, the reef can rapidly die. For Nevada, the identity was a growth-based economy rooted in gambling and tourism, and the threshold was water scarcity. Past a certain point, the available water supply would no longer support a growing population.

As it faced down this problem in the early 1990s, the Las Vegas metropolitan area had a serious handicap. What we call “Las Vegas” is not one city with a common government, but a collection of smaller cities–Las Vegas itself, plus Henderson, North Las Vegas, and large areas of unincorporated Clark County. A total of seven local water agencies often fussed and feuded rather than cooperating to deal with what was clearly a regional problem, not a local one.

The ability to band together to take collective action for the common good is a key to resilience in human systems. In Las Vegas, the first step was the 1991 formation of the Southern Nevada Water Authority, turning a competition among separate municipal water agencies into a regional collaboration. They pooled their water rights and agreed that when water became scarce, shortages would be shared. Moving beyond a “tragedy of the commons” to share a common pool resources is a key step toward resilience in the face of scarcity.

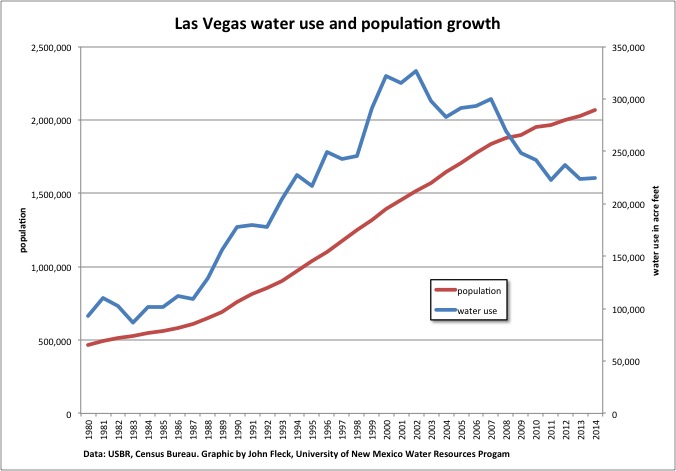

The Southern Nevada Water Authority created a regional framework for the pursuit of conservation, and pursue it Las Vegas did. With publicity campaigns, restrictions on landscaping in new construction, and policies like lawn buy-back programs, Las Vegas residents’ water use began to drop. From 1994 to 2014, per capita water use declined by 36 percent. Conservation soon outstripped population growth, such that total water use peaked in 2002 and has been declining ever since.

Where Las Vegas three decades ago looked like it was on the verge of outstripping its water supplies, this year it is using just 81 percent of its allotment from Lake Mead, its primary source of water. Over much of the last decade, it has been stashing surplus water in underground storage to provide a buffer against future shocks as drought and climate change loom over the region’s long-term water future.

Conservation is not the only benefit that came from the creation of the Southern Nevada Water Authority. Using local money, the Authority is building a new intake system to increase the reliability of the Lake Mead supply. And the agency has become a leader in the pursuit of regional water governance across the nine states (seven in the United States and two in Mexico) that must share the Colorado River’s water. Just as regional governance at the metropolitan level improved Las Vegas’s resilience, better water governance across the Colorado River Basin is increasing resilience at larger scales.

Las Vegas’s critics make an important point. A resilient future would be far easier for a smaller city. It is possible that the city’s water conservation measures, which allow Las Vegas to continue growing, will put more people at greater risk in a water-scarce future. But Las Vegas–like all communities–has chosen its own path. Perhaps its experience offers useful lessons for others.

This post was produced in collaboration with the Island Press Urban Resilience Project, with support from The Kresge Foundation and The JPB Foundation.

The featured image of the Treasure Island Las Vegas Hotel is courtesy of John Fleck.

John Fleck

John Fleck is the author of Water is for Fighting Over: and Other Myths about Water in the West, which tells the story of Las Vegas and the search for resilience in the arid West. Fleck is also Professor of Practice in Water Policy and Governance in the University of New Mexico Department of Economics, and is director of the University's Water Resources Program.